January 17, 2014 09:55 AM | Permalink |

Citizens for Tax Justice, January 17, 2014

Read this document in PDF.

The Senate Finance Committee’s discussion draft on international tax reform fails to accomplish what should be three goals for tax reform.

1. Raise revenue from the corporate income tax and the personal income tax.

2. Make the tax code more progressive.

3.Tax American corporations’ domestic and offshore profits at the same time and at the same rate.

The discussion draft would, in a proclaimed revenue-neutral manner, impose U.S. corporate taxes on offshore corporate profits in the year that they are earned. But it would do so at a lower rate than applies to domestic corporate profits.

The goal of revenue-neutrality causes the discussion draft to fail the first goal of raising revenue as well as the second, because any increase in corporate income tax revenue would make our tax system more progressive, as explained below. The discussion draft also fails to meet the third goal. Although it would tax domestic corporate profits and offshore corporate profits at the same time, it would subject the offshore profits to a lower rate, preserving some of the incentive for corporations to shift investment (and jobs) offshore or to engage in accounting gimmicks to make their U.S. profits appear to be generated in offshore tax havens.

1. Raise revenue from the corporate income tax, as well as from the personal income tax.

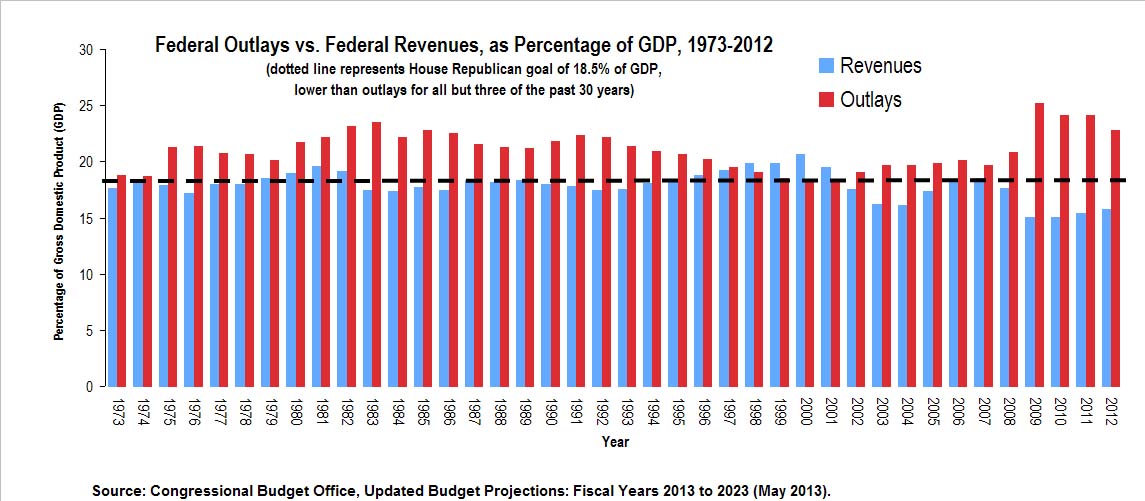

Some lawmakers see no reason to raise any revenue from either the corporate income tax or the personal income tax. These lawmakers’ fixation with addressing the budget deficit solely with spending cuts rather than revenue increases has resulted in the “sequestration” of federal spending in effect today, which cuts even those programs that are supported by large majorities of Americans as investments in our economic future, like Head Start and medical research.

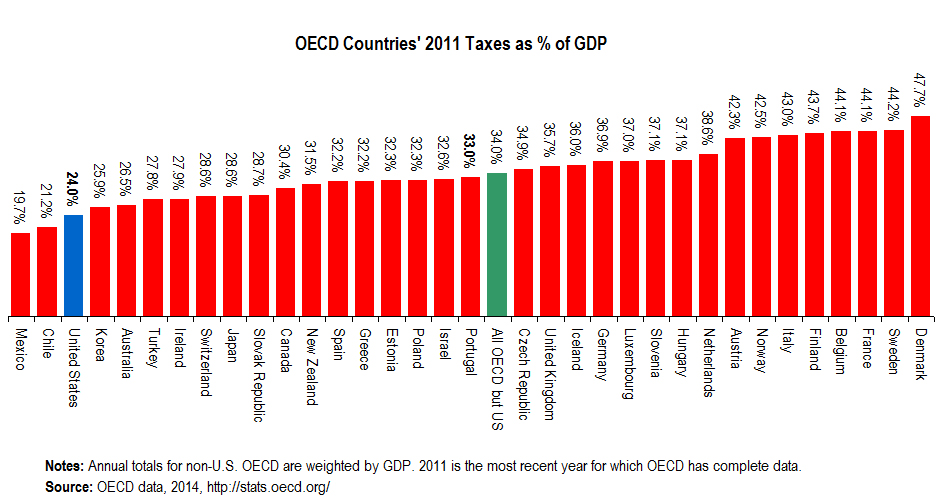

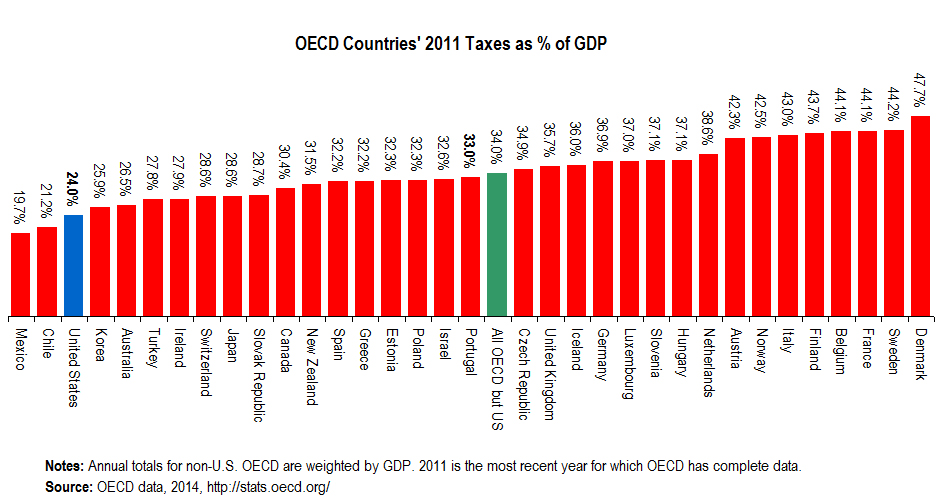

Almost all developed countries collect more in taxes as a share of their economies and therefore make greater public investments. As illustrated in the  graph above, in 2011, the most recent year for which there is complete data, the U.S. collected less tax revenue as a percentage of its economy than did any other OECD country except for Chile and Mexico.

graph above, in 2011, the most recent year for which there is complete data, the U.S. collected less tax revenue as a percentage of its economy than did any other OECD country except for Chile and Mexico.

Other lawmakers believe that tax reform should raise revenue, but only from the personal income tax. This, too, is very misguided. According to the Department of the Treasury and the Congressional Budget Office, federal corporate tax revenue in the U.S. was equal to 1.2 percent of our economy in 2011[1] (1.5 percent if you include state corporate taxes). The average for other OECD countries (which include most of the developed countries) in 2011 was 2.9 percent.

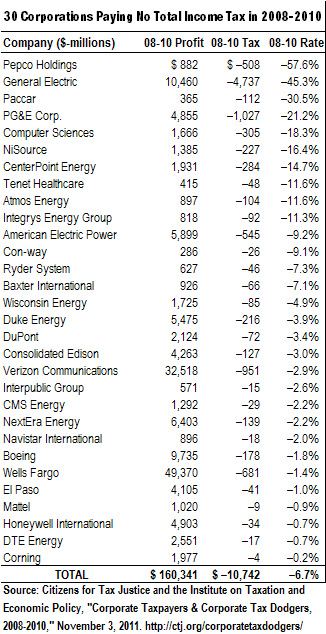

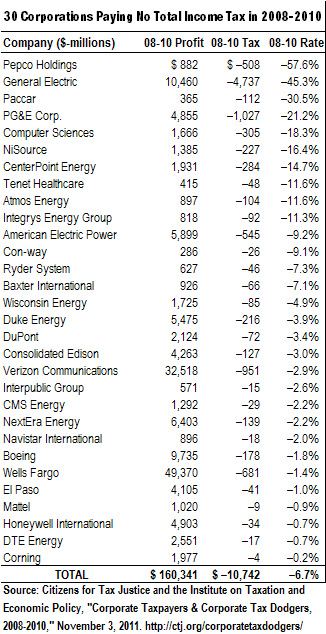

The federal corporate income tax today is so weak that it allows some American companies to avoid it completely even when they are profitable over several years. The figures in the table to the right are from CTJ’s study of the Fortune 500 corporations that were consistently profitable for three years straight.[2] Another finding from that study was that, of those profitable Fortune 500 corporations with significant offshore profits, two-thirds paid a higher effective corporate tax rate in the other countries where they do business than they paid in the U.S.

In other words, there is ample evidence that American corporations are undertaxed in the U.S. and can reasonably be expected to contribute more in tax revenue.

2. Make the tax code more progressive.

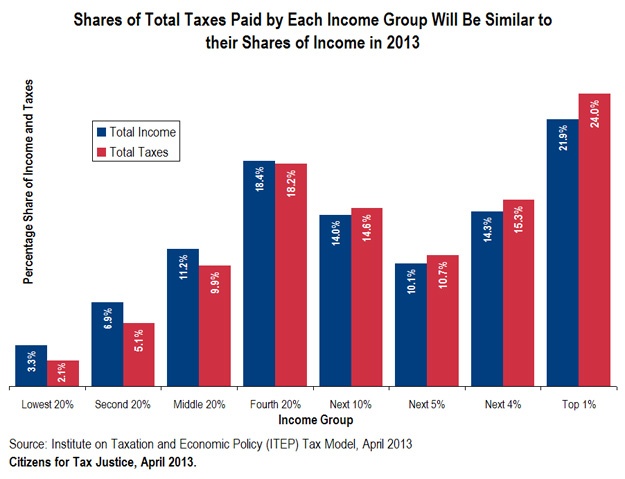

Because the corporate income tax is itself a progressive tax, raising revenue by closing corporate tax loopholes would make our tax system more progressive.

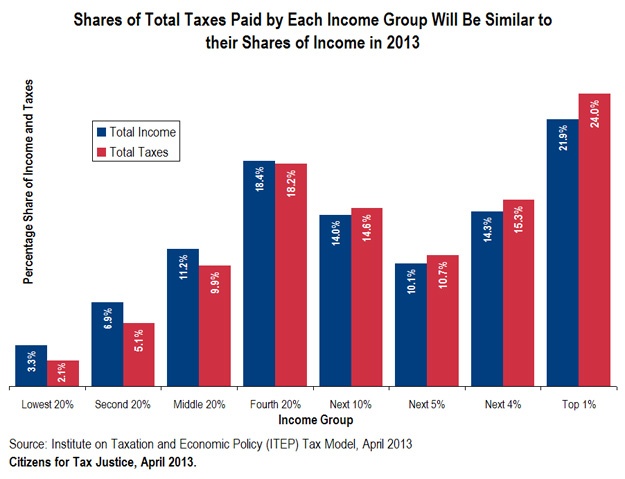

Contrary to what many lawmakers and pundits claim, our tax system as a whole is just barely progressive today. In fact, if one accounts for all the of the federal, state and local taxes that Americans pay, it turns out that the share of total taxes paid by each income group is roughly equal to the share of total income received by that group, as illustrated in the graph below. For example, the poorest fifth of taxpayers paid only 2.1 percent of total taxes in 2013, which is not so surprising given that this group received only 3.3 percent of total income. Meanwhile, the richest one percent of Americans paid 24 percent of total taxes and received 21.9 percent of total income in 2013.[3]

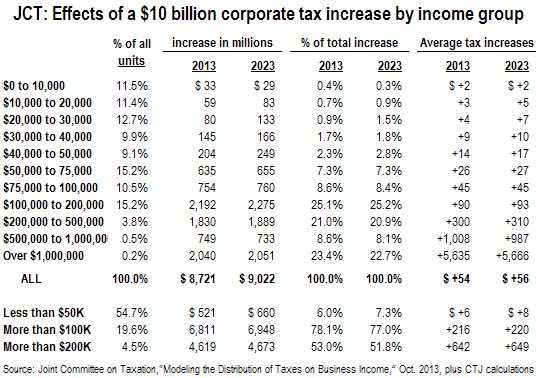

The Treasury Department and the Joint Committee on Taxation (JCT) have recently confirmed that the corporate income tax is a progressive tax. It is clear that the corporate tax is, in the short-term, borne by the (mostly wealthy) owners of capital — meaning it’s paid by the owners of corporate stocks and other business and investment assets because the tax reduces what corporations can pay out as dividends to their shareholders. The Treasury Department concluded that even in the long-run, 82 percent of the tax is borne by owners of capital.[4] The rest is borne by labor.

The Treasury Department and the Joint Committee on Taxation (JCT) have recently confirmed that the corporate income tax is a progressive tax. It is clear that the corporate tax is, in the short-term, borne by the (mostly wealthy) owners of capital — meaning it’s paid by the owners of corporate stocks and other business and investment assets because the tax reduces what corporations can pay out as dividends to their shareholders. The Treasury Department concluded that even in the long-run, 82 percent of the tax is borne by owners of capital.[4] The rest is borne by labor.

Opponents of the corporate tax sometimes argue that a much higher portion is borne by labor — by workers who ultimately suffer lower wages or unemployment because the corporate tax allegedly pushes investment (and jobs) offshore.

The Treasury Department concluded that such investment is not so mobile in this way. This is reinforced by JCT’s recent conclusion that, in the long-run, 75 percent of the corporate income tax is borne by owners of capital.[5]

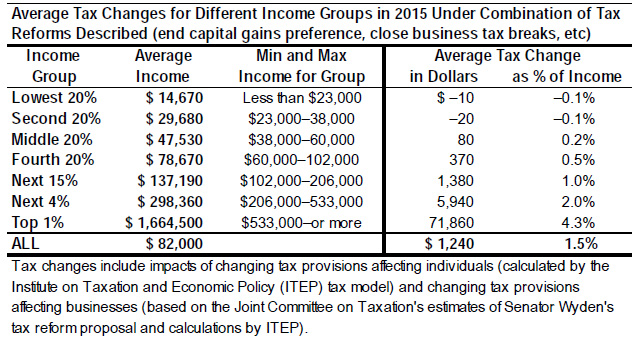

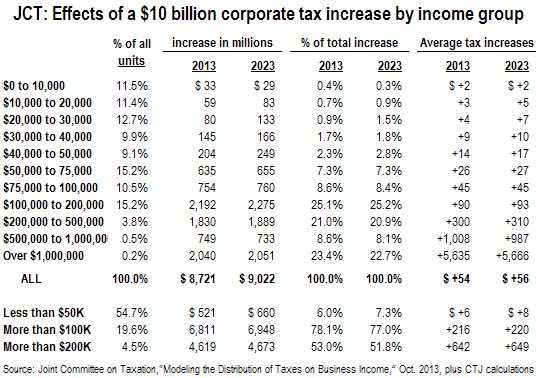

The table below includes JCT’s estimates of the tax increase that would result for each income group if the corporate income tax was increased by $10 billion, along with CTJ’s calculations of the average tax increase and share of the total tax increase for each income group. It shows that over half of a corporate income tax increase would be paid by people with income exceeding $200,000. Well over three-fourths would be paid by people with incomes exceeding $100,000. Only about 6 percent would be paid by the 55 percent of taxpayers earning less than $50,000, whose average tax increase from a $10 billion corporate tax hike would be only $6 to $8.

3. Tax American corporations’ domestic and offshore profits at the same time and at the same rate.

Taxing the offshore profits of American corporations more lightly than their domestic profits can create two terrible incentives for corporations. First, in some situations it encourages them to shift their operations and jobs to a country with lower taxes. Second, it encourages them to use accounting gimmicks to disguise their U.S. profits as foreign profits generated by a subsidiary company in some other country that has much lower taxes or that doesn’t tax these profits at all.

The countries that have extremely low taxes or no taxes on profits are known as tax havens. And the subsidiary companies in the tax havens that are claimed to make all these profits are often nothing more than post office boxes.

There are two ways we can tax corporate profits that are officially “offshore” more lightly than domestic profits and thus create these terrible incentives. The first way is what our tax rules do now when they allow American corporations to “defer” (delay indefinitely) paying U.S. taxes on their offshore profits until those profits are officially “repatriated” (officially brought to the U.S.). The second way is to tax corporate profits that are officially offshore at a lower rate than domestic corporate profits. A version of this is the offshore minimum tax proposed in the Senate Finance Committee’s discussion draft on international tax reform.

Neither deferral nor a lower tax rate is needed to protect offshore corporate profits from double-taxation. Another feature of our tax rules, the foreign tax credit, prevents double-taxation by allowing American corporations to subtract whatever corporate tax they paid to foreign governments from the U.S. corporate tax owed on their offshore profits. In other words, the deferral rule we have now, and the lower tax rate for foreign profits proposed by the Finance Committee are both unnecessary breaks for profits characterized as “offshore.”

To be sure, the minimum tax for offshore profits proposed by the Finance Committee would certainly cause some of the worst corporate tax dodgers to pay some U.S. taxes on profits that are entirely tax-free under the current rules. These are profits that are earned in the U.S. (or in other countries with a corporate tax) but manipulated through accounting gimmicks to appear to be earned in tax haven countries.

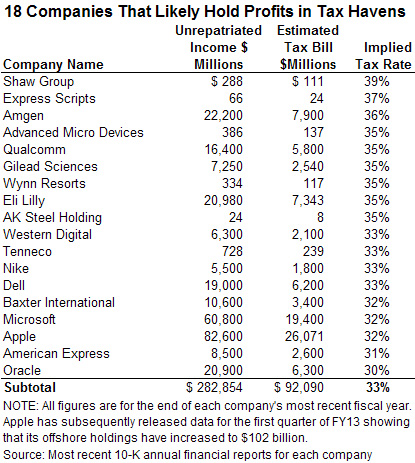

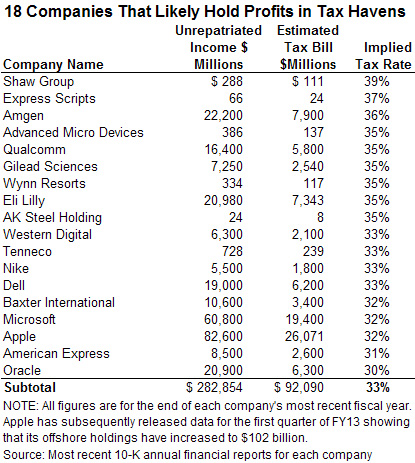

There is ample evidence of specific American corporations holding their profits in offshore tax havens. Some corporations divulge, in their public filings with the Securities and Exchange Commission, how much they would pay in U.S. taxes if they “repatriated” their offshore profits (officially brought their offshore profits to the U.S.) And some of these corporations — like American Express, Apple, Dell, Microsoft, Nike and others — indicate that they would pay nearly the full U.S. corporate income tax rate of 35 percent.[6] This is another way of saying that these corporations would receive very little, if any, credits to offset foreign taxes paid, because they have not paid much, if anything, in taxes to any foreign government.

This is an indication that the corporations’ offshore profits are held (officially, at least) in countries with no corporate income taxes — tax havens. Most of the countries that have consumer markets and developed economies where American companies can sell products also have corporate taxes. Most countries that do not have corporate income taxes are small countries like Bermuda and the Cayman Islands that provide little in the way of real business opportunities but are useful to multinational corporations as tax havens.

This is an indication that the corporations’ offshore profits are held (officially, at least) in countries with no corporate income taxes — tax havens. Most of the countries that have consumer markets and developed economies where American companies can sell products also have corporate taxes. Most countries that do not have corporate income taxes are small countries like Bermuda and the Cayman Islands that provide little in the way of real business opportunities but are useful to multinational corporations as tax havens.

Recent data from the Congressional Research Service (CRS) confirms that this sort of corporate tax dodging involving offshore tax havens is happening on a massive scale. For example, CRS finds that the profits that American corporations claimed (to the IRS) to have earned through subsidiaries in Bermuda in 2008 equaled 1,000 percent of that tiny country’s economy, which is clearly impossible.[7]

The minimum tax for offshore profits proposed in the discussion draft would certainly raise corporate taxes on the profits shifted (on paper) into a tax haven like Bermuda because under the current rules these profits are not taxed at all.

But the incentive for corporations to use complicated tricks to make their U.S. profits appear to be earned in tax havens will exist so long as offshore profits continue to be taxed more lightly than domestic profits, which would continue to be the case under the Finance Committee’s discussion draft.

One version of the proposed minimum tax would require that profits generated in other countries be taxed at a rate that is at least some unspecified percentage of the regular U.S. corporate tax rate. The Committee has not yet decided what general corporate tax rate will be proposed or what percentage of that must be paid in tax on foreign profits. (The discussion draft suggests that it could be 80 percent of the regular corporate tax rate but says this will likely be adjusted as the tax reform plan takes shape.)

If one assumes that the general corporate tax rate is 28 percent and the minimum tax for offshore profits is 80 percent of that, then the proposed rule would require that foreign profits be taxed at a rate of at least 22.4 percent. If they are taxed by the foreign country at a rate of, say, 18 percent, that would mean the corporation would pay U.S. corporate taxes of 4.4 percent. (18+4.4=22.4).

If the minimum tax for offshore profits is lower than 80 percent of the regular corporate income tax rate, then the proposed rule would be even less effective. (On the other hand, if it is 100 percent of the regular corporate tax rate, then the proposed rule would be the approach that we favor.)

The other version of the minimum tax offered in the discussion draft would tax “passive” offshore profits at 100 percent of the regular corporate tax rate but would tax “active” offshore profits at a lower, unspecified percentage of the regular corporate tax rate. (The discussion draft suggests that “active” offshore profits could be 60 percent of the regular corporate tax rate.)

The concept of “active” income and “passive” income already is a major part of our tax code, but the discussion draft would define them differently for this option. The basic idea is that “passive” income (like interest payments, rents and royalties) is income that is extremely easy to move from one subsidiary to another and therefore easily used for tax avoidance if it’s not taxed at the full U.S. rate.

This second option has some conceptual appeal if the only goal is to try to crack down on offshore profit shifting. But the definitions of passive and active would likely lead to schemes to characterize passive income as active, as happens under current law. Moreover, this rule would do little to reduce incentives to move actual investment and jobs offshore.

Conclusion

The first problem with the Finance Committee’s discussion draft on international tax reform is that it does not attempt to raise badly needed revenue from the corporate income tax. This leads to the second problem, which is that the discussion draft passes by an opportunity to add some badly needed progressivity to America’s tax system.

The third problem with the discussion draft is that it would continue to tax corporate profits that are booked offshore more lightly than those booked in the U.S. Our position remains that a reformed code should tax corporate profits at the same time and at the same rate regardless of whether they are booked offshore or in the U.S.

In other words, our position remains that international corporate tax reform should include full repeal of deferral (along with a per-country rule for foreign tax credits) and a single tax rate for both offshore and domestic profits, as has been proposed by Senator Ron Wyden.[8] This simple approach would both solve the tax-haven problem and reduce tax incentives for moving investment and jobs offshore. And our position remains that the corporate tax rate should not be reduced significantly below the current 35 percent rate, because doing so would make it very difficult to meet the goals of raising revenue and increasing progressivity.

[1] Congressional Budget Office, “Updated Budget Projections: Fiscal Years 2013 to 2023,” May 2013, “Historical Budget Data.” http://cbo.gov/publication/44197

[2] Citizens for Tax Justice, “Corporate Taxpayers & Corporate Tax Dodgers, 2008-2010,” November 3, 2011. www.ctj.org/corporatetaxdodgers

[3] For more see Citizens for Tax Justice, “Who Pays Taxes in America in 2013?,” April 1, 2013. http://ctj.org/ctjreports/2013/04/who_pays_taxes_in_america_in_2013.php; Citizens for Tax Justice, “New Tax Laws in Effect in 2013 Have Modest Progressive Impact,” April 1, 2013. http://ctj.org/ctjreports/2013/04/new_tax_laws_in_effect_in_2013_have_modest_progressive_impact.php

[4] Julie-Anne Cronin, Emily Y. Lin, Laura Power, and Michael Cooper, “Distributing the Corporate Income Tax: Revised U.S. Treasury Methodology,” Treasury Department, 2012. http://www.treasury.gov/resource-center/tax-policy/tax-analysis/Documents/OTA-T2012-05-Distributing-the-Corporate-Income-Tax-Methodology-May-2012.pdf

[5] Joint Committee on Taxation, “Modeling The Distribution Of Taxes On Business Income,” October 16, 2013. https://www.jct.gov/publications.html?func=startdown&id=4528

[6] Citizens for Tax Justice, “Apple Is Not Alone,” June 2, 2013. http://ctj.org/ctjreports/2013/06/apple_is_not_alone.php

[7] Mark P. Keightley, “An Analysis of Where American Companies Report Profits: Indications of Profit Shifting,” Congressional Research Service, January 18, 2013.

[8] Citizens for Tax Justice, “Working Paper on Tax Reform Options,” February 4, 2013. www.ctj.org/ctjreports/2013/02/working_paper_on_tax_reform_options.php

![]()

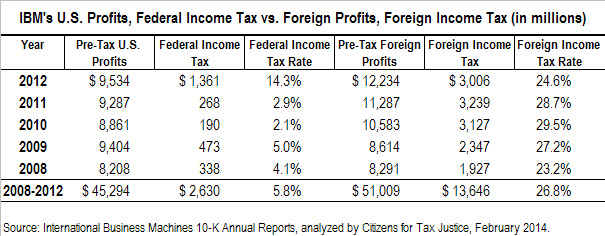

engage in accounting gimmicks to make most of its U.S. profits appear (to the IRS) to be earned in subsidiaries in Bermuda, the Cayman Islands or other countries that do not tax these profits. Of course, IBM does little or no real business in these countries and its subsidiaries there may be nothing more than post office boxes.

engage in accounting gimmicks to make most of its U.S. profits appear (to the IRS) to be earned in subsidiaries in Bermuda, the Cayman Islands or other countries that do not tax these profits. Of course, IBM does little or no real business in these countries and its subsidiaries there may be nothing more than post office boxes.

graph above, in 2011, the most recent year for which there is complete data, the U.S. collected less tax revenue as a percentage of its economy than did any other OECD country except for Chile and Mexico.

graph above, in 2011, the most recent year for which there is complete data, the U.S. collected less tax revenue as a percentage of its economy than did any other OECD country except for Chile and Mexico. The Treasury Department and the Joint Committee on Taxation (JCT) have recently confirmed that the corporate income tax is a progressive tax. It is clear that the corporate tax is, in the short-term, borne by the (mostly wealthy) owners of capital — meaning it’s paid by the owners of corporate stocks and other business and investment assets because the tax reduces what corporations can pay out as dividends to their shareholders. The Treasury Department concluded that even in the long-run, 82 percent of the tax is borne by owners of capital.

The Treasury Department and the Joint Committee on Taxation (JCT) have recently confirmed that the corporate income tax is a progressive tax. It is clear that the corporate tax is, in the short-term, borne by the (mostly wealthy) owners of capital — meaning it’s paid by the owners of corporate stocks and other business and investment assets because the tax reduces what corporations can pay out as dividends to their shareholders. The Treasury Department concluded that even in the long-run, 82 percent of the tax is borne by owners of capital.

This is an indication that the corporations’ offshore profits are held (officially, at least) in countries with no corporate income taxes — tax havens. Most of the countries that have consumer markets and developed economies where American companies can sell products also have corporate taxes. Most countries that do not have corporate income taxes are small countries like Bermuda and the Cayman Islands that provide little in the way of real business opportunities but are useful to multinational corporations as tax havens.

This is an indication that the corporations’ offshore profits are held (officially, at least) in countries with no corporate income taxes — tax havens. Most of the countries that have consumer markets and developed economies where American companies can sell products also have corporate taxes. Most countries that do not have corporate income taxes are small countries like Bermuda and the Cayman Islands that provide little in the way of real business opportunities but are useful to multinational corporations as tax havens.

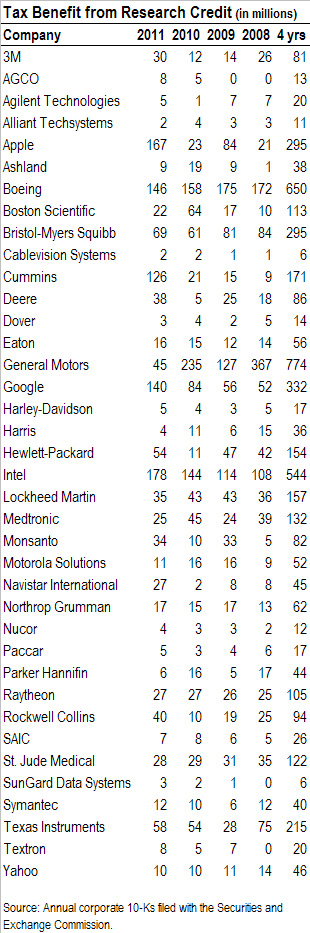

Congress should let the research credit expire, and redirect the billions of dollars that it costs into true, basic, truly scientific research, which businesses rarely engage in because the payoffs often take years to arrive.

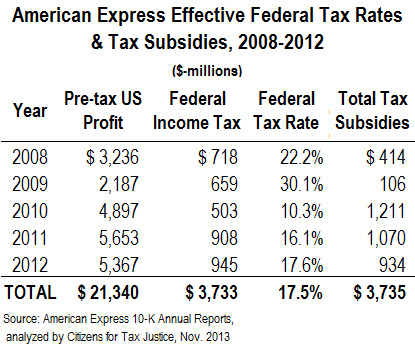

Congress should let the research credit expire, and redirect the billions of dollars that it costs into true, basic, truly scientific research, which businesses rarely engage in because the payoffs often take years to arrive. Even on the $21.3 billion in pretax profits that American Express officially earned in the U.S. over the past five years, the company has paid only half the 35 percent federal statutory tax rate. This means that over the past five years, American Express received over $3.7 billion in tax subsidies through the US tax code.

Even on the $21.3 billion in pretax profits that American Express officially earned in the U.S. over the past five years, the company has paid only half the 35 percent federal statutory tax rate. This means that over the past five years, American Express received over $3.7 billion in tax subsidies through the US tax code.

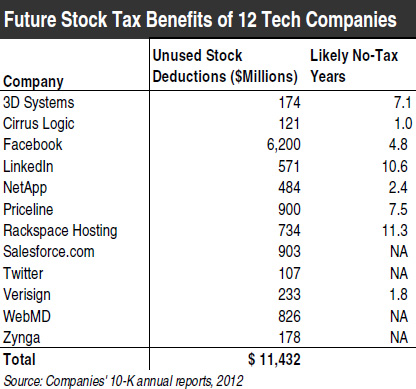

–Twitter has $107 million of unused stock option deductions—meaning that the next $107 million the company earns could be tax-free as a result of this single tax break. (Since the company has not yet reported a profitable year in the US, it’s impossible to estimate how long it will take the company to earn this amount going forward.)

–Twitter has $107 million of unused stock option deductions—meaning that the next $107 million the company earns could be tax-free as a result of this single tax break. (Since the company has not yet reported a profitable year in the US, it’s impossible to estimate how long it will take the company to earn this amount going forward.)