September 22, 2014 11:48 AM | Permalink |

Read this report in PDF.

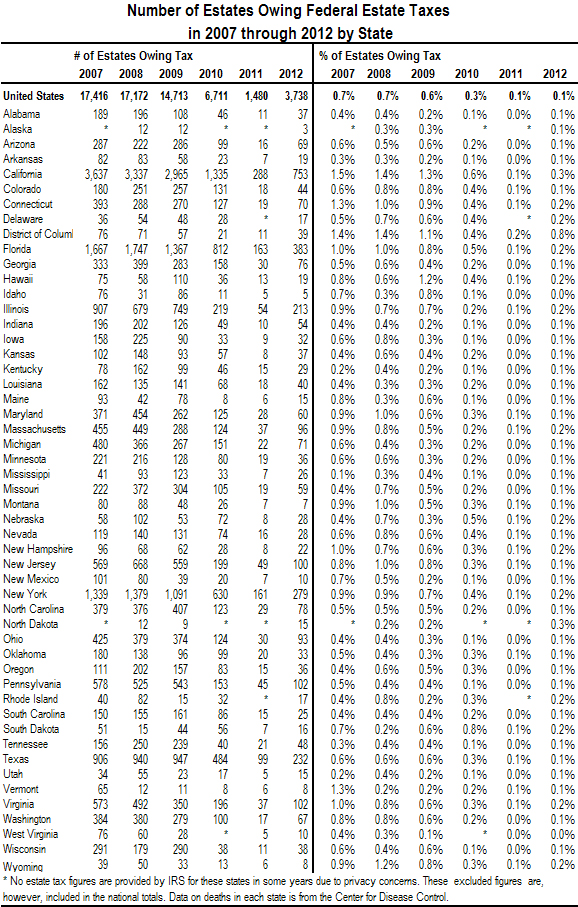

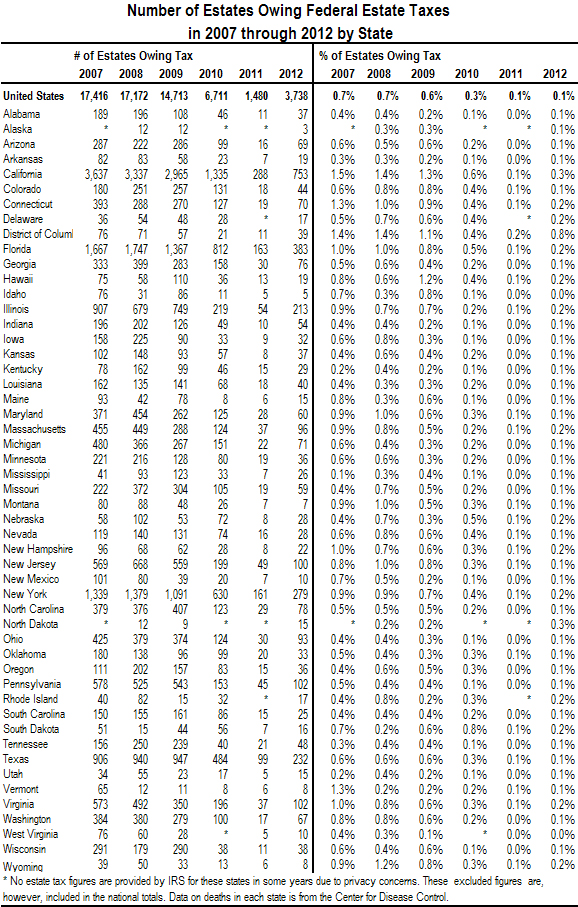

New data from the IRS show that only 0.1 percent — just one-tenth of one percent — of deaths in the U.S. in 2011 resulted in federal estate tax liability in 2012. (Estate taxes are usually filed the year after a person dies.) To restore some of the revenue lost when the estate tax was scaled back in recent years, Congress should enact a proposal from Senator Bernie Sanders that would restore exemption amounts in effect in 2009, but would subject the largest estates to higher rates. These figures show that only 0.3 percent of deaths in 2009 resulted in estate tax liability, which is an indication that under Sen. Sanders’ proposal the estate tax would still only affect the very largest estates.

Why the Estate Tax is Important

The estate tax is a way of acknowledging that the wealthiest families benefit the most from what the government provides: public investments like roads that make commerce possible, public schools that provide a productive workforce, the stability provided by our legal system and armed forces, the protection of private property. These public investments make America a place where huge fortunes can be made and sustained. None of this would be possible without taxes, so it’s reasonable that the wealthiest families contribute more to support these public services. At the same time, the estate tax has provisions to ensure that it only applies to the wealthy, encourages charitable giving and does not impact family farms and small businesses.

Just as important is the tax’s function as a mitigator of gross wealth inequality in the United States. Highly concentrated wealth threatens the essence of democracy, giving some groups greater political leverage and creating disparities in economic opportunity. Viewed this way, the estate tax is now more critical than ever: in 2010, the wealthiest 1 percent of Americans owned 35 to 37 percent of the wealth nationwide.

A Recent History of the Estate Tax

The estate tax makes use of a basic per-spouse exemption to ensure that only wealthy households are impacted. Only the portion of the estate that exceeds the exemption threshold is subject to tax. The tax also provides deductions for things like funeral expenses, mortgages and other debts, bequests to surviving spouses, and charitable donations, further reducing the amount of the estate that is actually taxable. Over the past decade, changes in the structure of the federal estate tax have drastically reduced the number of estates subject to the tax, effectively exempting even many wealthy households from taxation.

The first round of President George W. Bush’s tax cuts, enacted in 2001, included gradual repeal of the federal estate tax over several years. The amount of estate value exempt from the tax increased over time, and the tax rate decreased over time, until the federal estate tax disappeared in 2010.

In 2007 and 2008, the basic exemption was $2 million per spouse and the top estate tax rate was 45 percent. Of those who died in 2008, only 0.6 percent left estates large enough to be taxable in 2009. (Estate taxes are usually filed the year after the year of death.)

In 2009, the basic exemption rose to $3.5 million per spouse, and the top estate tax rate continued to be 45 percent. Of those who died in 2009, only 0.3 percent left estates large enough to be taxable in 2010. This is likely representative of the share of deaths that would be subject to the estate tax under Senator Sanders’ bill, which includes an exemption of $3.5 million per spouse.

In 2010, the estate tax was eliminated. (A small number of estates are not taxed the year after death but rather in the same year as death or several years later, which is why a small number of estates were taxed in 2011.)

Like all the Bush tax cuts, this break from the estate tax was scheduled to expire at the end of 2010, in which case the pre-Bush rules would come back into effect.

President Obama and Congress agreed to a compromise at the end of 2010 to (among other things) extend the Bush income tax cuts and partially extend Bush’s break from the estate tax. As part of this deal, lawmakers reinstated the estate tax but with a higher basic exemption of $5 million per spouse and a rate of just 35 percent in 2011 and 2012. A mere 0.1 percent of deaths in 2011 resulted in estate tax liability in 2012.

As part of the fiscal cliff deal reached at the end of 2012, the higher basic exemption level set during the 2010 compromise was permanently extended and indexed to inflation, and the rate was increased from 35 percent to 40 percent. When data for deaths in 2013 eventually becomes available, the extension of this exemption level should be reflected in a continuing historically low percentage of estates subject to tax.

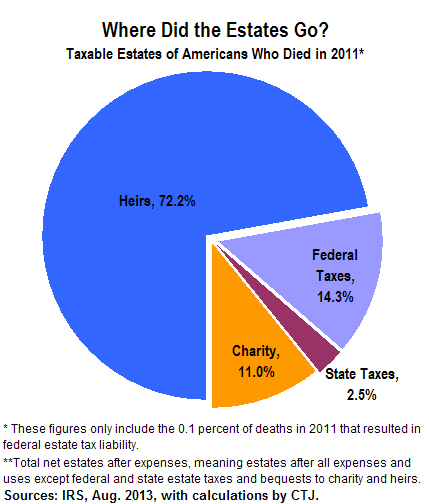

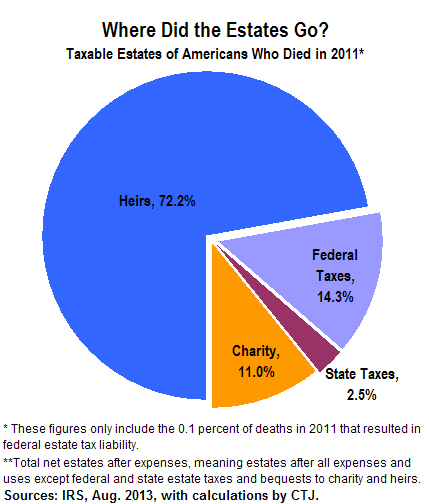

The pie chart below shows that the 0.1 percent of estates taxed in 2012 (mostly estates of people who died in 2011) were taxed at an effective rate of about 14 percent by the federal government. More than 72 percent of the value of those estates was left to heirs while 11 percent was left to charity. The increase in the tax rate effective in 2013 should be reflected beginning with estates that file in 2014 in a slightly larger share of taxable estates going toward federal taxes.

Senator Bernie Sanders’ Responsible Estate Tax Act

Like President Obama in his recent budget plans, Sen. Sanders proposes to bring back the basic estate tax exemption of $3.5 million per spouse, which was in effect in 2009. Only 0.3 percent of deaths in 2009 resulted in estate tax liability, and therefore a similar percentage of deaths would result in estate tax liability under either of these proposals.

According to the Joint Committee on Taxation, President Obama’s estate tax proposal would raise $85 billion over a decade. Senator Sanders’ proposal would likely raise more because it includes a graduated rate structure.

Rather than simply reinstate the 45 percent rate that was in effect in 2009, Sen. Sanders’ Responsible Estate Tax Act would tax the value of an estate above $3.5 million and below $10 million at 40 percent. It would tax the value of estates above $10 million and below $50 million at 50 percent, and the value of estates above $50 million at 55 percent. It would also apply an additional surtax of ten percent on estates worth over $1 billion.

Both the President’s proposal and the Responsible Estate Tax Act would close certain loopholes in the estate tax. For example, one provision in both proposals would “require a minimum term for GRATs.”

A person owning an asset with a quickly rising value may want to find some way to “lock in” its current value for purposes of calculating estate and gift taxes before it rises any further. One way is to place the asset in a certain type of trust (a Grantor Retained Annuity Trust, or GRAT) that pays an annuity for a certain time and then leaves whatever assets remain to the trust’s beneficiaries.

The gift to the trust’s beneficiaries is valued when the trust is set up, rather than when it’s received by the beneficiaries. This benefit is particularly difficult to justify when the trust has a very short term (perhaps just a couple years) and wealthy people have used such short-term trusts to aggressively reduce or even eliminate any tax on gifts to their children. The proposals would require a GRAT to have a minimum term of 10 years, increasing the chance that the grantor will die during the GRAT’s term and the assets will be included in the grantor’s estate and thus subject to the estate tax.

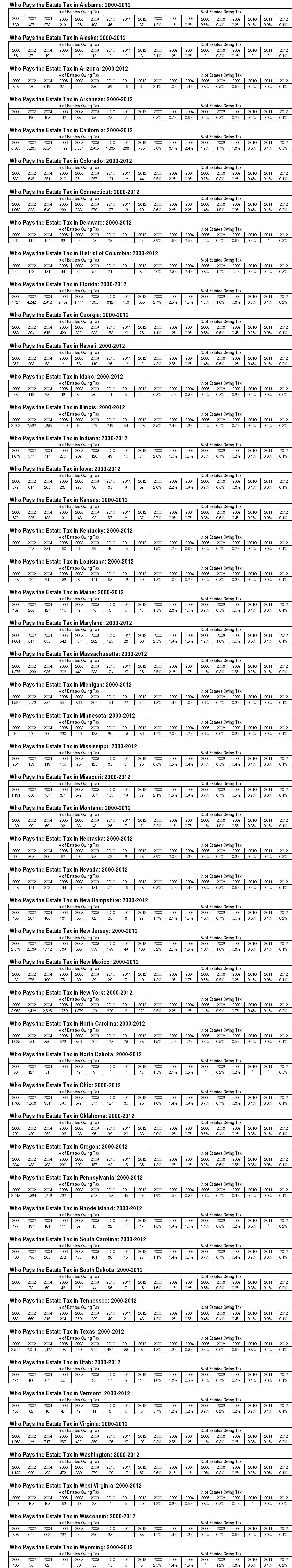

More State-by-state Figures

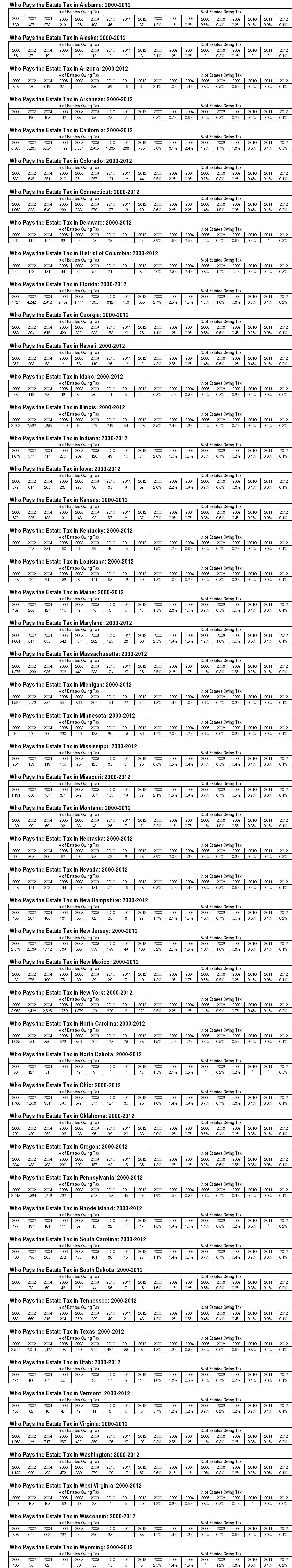

The following pages provide figures on the number and percentage of estates in each state that are subject to the federal estate tax. (For easier reading, see the PDF version of this report, which also includes these tables.)

Political leaders in New Jersey could be close to figuring out a fix for the state’s transportation funding crisis. The Transportation Trust Fund is set to run out of money soon, and Gov. Chris Christie has declared that all options are on the table — including, perhaps, an increase in the gas tax, which is currently second lowest in the nation (it has been more than 20 years since the tax was increased). The pledge represents a softening of the governor’s position; he has opposed any increase in the gas tax in recent years, and has also raided the trust fund to balance the state budget. State lawmakers could also consider indexing the gas tax to inflation, as they’ve done in Massachusetts, or applying the state’s sales tax to gasoline purchases, as advocated by New Jersey Policy Perspective, a leading nonpartisan think tank in the state.

Political leaders in New Jersey could be close to figuring out a fix for the state’s transportation funding crisis. The Transportation Trust Fund is set to run out of money soon, and Gov. Chris Christie has declared that all options are on the table — including, perhaps, an increase in the gas tax, which is currently second lowest in the nation (it has been more than 20 years since the tax was increased). The pledge represents a softening of the governor’s position; he has opposed any increase in the gas tax in recent years, and has also raided the trust fund to balance the state budget. State lawmakers could also consider indexing the gas tax to inflation, as they’ve done in Massachusetts, or applying the state’s sales tax to gasoline purchases, as advocated by New Jersey Policy Perspective, a leading nonpartisan think tank in the state.

It explains that some states in the U.S. require less identification from people forming corporations than they require from those applying for a library card. We have long noted that one result is the use of anonymous corporations formed in the U.S. for tax evasion by Americans and by people from all over the world, which in turn makes it much more difficult to persuade other countries to cooperate with the U.S. in stamping out tax evasion.

It explains that some states in the U.S. require less identification from people forming corporations than they require from those applying for a library card. We have long noted that one result is the use of anonymous corporations formed in the U.S. for tax evasion by Americans and by people from all over the world, which in turn makes it much more difficult to persuade other countries to cooperate with the U.S. in stamping out tax evasion.