What Fortune 500 Firms Pay (or Don’t Pay) in the USA And What they Pay Abroad — 2008 to 2012

Read the Report in PDF (Includes Company by Company Appendices and Footnotes)

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

Profitable corporations are supposed to pay a 35 percent federal income tax rate on their U.S. profits. But many corporations pay far less, or nothing at all, because of the many tax loopholes and special breaks they enjoy. This report documents just how successful many Fortune 500 corporations have been at using these loopholes and special breaks over the past five years.

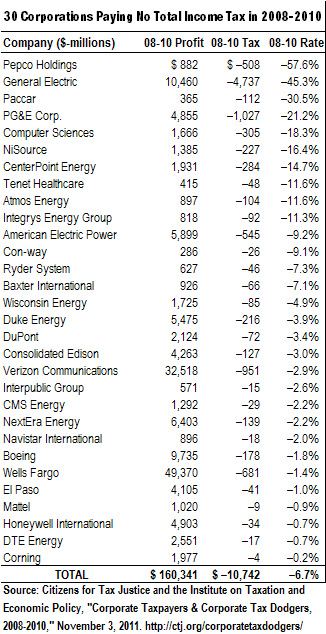

The report looks at the profits and U.S. federal income taxes of the 288 Fortune 500 companies that have been consistently profitable in each of the five years between 2008 and 2012, excluding companies that experienced even one unprofitable year during this period. Most of these companies were included in our November 2011 report, Corporate Taxpayers and Corporate Tax Dodgers, which looked at the years 2008 through 2010. Our new report is broader, in that it includes companies, such as Facebook, that have entered the Fortune 500 since 2011, and narrower, in that it excludes some companies that were profitable during 2008 to 2010 but lost money in 2011 or 2012.

Some Key Findings:

- As a group, the 288 corporations examined paid an effective federal income tax rate of just 19.4 percent over the five-year period — far less than the statutory 35 percent tax rate.

- Twenty-six of the corporations, including Boeing, General Electric, Priceline.com and Verizon, paid no federal income tax at all over the five year period. A third of the corporations (93) paid an effective tax rate of less than ten percent over that period.

- Of those corporations in our sample with significant offshore profits, two thirds paid higher corporate tax rates to foreign governments where they operate than they paid in the U.S. on their U.S. profits.

These findings refute the prevailing view inside the Washington, D.C. Beltway that America’s corporate income tax is more burdensome than the corporate income taxes levied by other countries, and that this purported (but false) excess burden somehow makes the U.S. “uncompetitive.”

Other Findings:

- One hundred and eleven of the 288 companies (39 percent of them) paid zero or less in federal income taxes in at least one year from 2008 to 2012.

- The sectors with the lowest effective corporate tax rates over the five-year period were utilities (2.9 percent), industrial machinery (4.3 percent), telecommunications (9.8 percent), oil, gas and pipelines (14.4 percent), transportation (16.4 percent), aerospace and defense (16.7 percent) and financial (18.8 percent).

- The tax breaks claimed by these companies are highly concentrated in the hands of a few very large corporations. Just 25 companies claimed $174 billion in tax breaks over the five years between 2008 and 2012. That’s almost half the $364 billion in tax subsidies claimed by all of the 288 companies in our sample.

- Five companies — Wells Fargo, AT&T, IBM, General Electric, and Verizon — enjoyed over $77 billion in tax breaks during this five-year period.

Recommendations for Reform:

- Congress should repeal the rule allowing American multinational corporations to indefinitely “defer” their U.S. taxes on their offshore profits. This reform would effectively remove the tax incentive to shift profits and jobs overseas.

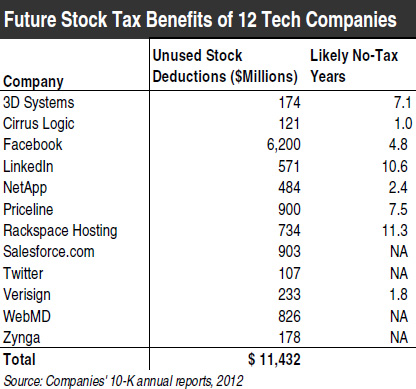

- Limit the ability of tech and other companies to use executive stock options to reduce their taxes by generating phantom “costs” these companies never actually incur.

- Having allowed “bonus depreciation” to expire at the end of 2013, Congress could take the next step and repeal the rest of accelerated depreciation, too.

- Reinstate a strong corporate Alternative Minimum Tax that really does the job it was originally designed to do.

- Require more complete and transparent geography-specific public disclosure of corporate income and tax payments than the Securities and Exchange Commission’s regulations currently mandate.

INTRODUCTION

Last year, a U.S. Senate committee wrapped up an extensive investigation into techniques used by giant technology firms, including Apple and Microsoft, to avoid paying corporate income taxes in the United States and abroad. The committee’s findings showed that some of the most profitable U.S.-based multinationals are finding ways to artificially shift their profits, on paper, from the United States to low-tax havens where they do little or no real business. At the same time, corporate lobbyist groups have engaged in an aggressive push on Capitol Hill to reduce the federal corporate income tax rate, based on the claim that our corporate tax is uncompetitively high compared to other developed nations.

Do American corporations really pay higher taxes in the United States than they do abroad? Do they pay anything close to the 35 percent U.S. tax rate that corporate lobbyists have complained about so vocally? This study takes a hard look at federal income taxes paid or not paid by 288 of America’s largest and most profitable corporations in the five years between 2008 and 2012 — and compares these tax payments to the foreign taxes that a multinational subset of these same companies pay on their activities in the rest of the world. The companies in our report are all from Fortune’s annual list of America’s 500 largest corporations, and all of them were profitable in the United States in each of the five years analyzed. Over five years, the 288 companies in our survey reported total pretax U.S. profits of more than $2.3 trillion.

While the federal corporate tax law ostensibly requires big corporations to pay a 35 percent corporate income tax rate, the 288 corporations in our study on average paid barely more than half that amount: 19.4 percent over the 2008-12 period. Many companies paid far less, including 26 that paid nothing at all over the entire five-year period.

We also find that for most of the multinationals in our survey — companies that engage in significant business both in the United States and abroad — the U.S. tax rates these companies pay are lower than the rates they face abroad. Two-thirds of the multinationals in our survey enjoyed lower U.S. tax rates on their U.S. profits than the foreign tax rates they paid on their foreign profits.

There is wide variation in the tax rates paid by the companies surveyed. A quarter of the companies in this study paid effective federal income tax rates on their U.S. profits close to the full 35 percent official corporate tax rate. But almost one-third paid less than 10 percent. One hundred and eleven of these profitable companies found ways to zero out every last dime of their federal income tax in at least one year during the five-year period.

There is plenty of blame to share for today’s sad situation. Corporate apologists will correctly point out that loopholes and tax breaks that allow low-tax corporations to minimize or eliminate their income taxes are generally legal, and that they stem from laws passed over the years by Congress and signed by various Presidents. But that does not mean that low tax corporations bear no responsibility. The tax laws were not enacted in a vacuum; they were adopted in response to relentless corporate lobbying, threats and campaign support.

|

PREVIOUS CTJ & ITEP CORPORATE TAX STUDIES • Corporate Income Taxes in the Reagan Years (Citizens for Tax Justice 1984) • The Failure of Corporate Tax Incentives (CTJ 1985) • Corporate Taxpayers and Corporate Freeloaders (CTJ 1985) • Money for Nothing (CTJ & the Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy 1986) • 130 Reasons Why We Need Tax Reform (CTJ & ITEP1986) • The Corporate Tax Comeback (CTJ & ITEP 1986) • It’s Working, But… (CTJ & ITEP 1989) • Corporate Income Taxes in the 1990s (ITEP 2000) • Corporate Income Taxes in the Bush Years (CTJ & ITEP 2004) • Corporate Taxpayers and Corporate Tax Dodgers (CTJ & ITEP 2011) |

The good news is that the corporate income tax can be repaired. The parade of industry-specific and even company-specific tax breaks that lard the corporate tax can — and should — be repealed. This includes tax giveaways as narrow as the NASCAR depreciation tax break and as broad as the manufacturing deduction. High-profile multinational corporations that have shifted hundreds of billions of their U.S. income into tax havens for tax purposes, without actually engaging in any meaningful activity in those tiny countries, will stop doing so if Congress acts to end indefinite deferral of U.S. taxes on their offshore profits. As Congress considers these steps, lawmakers and the Securities and Exchange Commission should take steps to ensure that they, and the public, have access to basic information about how much big companies are paying in taxes and which tax breaks they’re claiming.

This study is the latest in a series of comprehensive corporate tax reports by Citizens for Tax Justice and the Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, beginning in 1984. Our most recent prior report, issued in 2011, covered corporate taxes in 2008 through 2010. The methodological appendix at the end of the study explains in more detail how we chose the companies and calculated their effective tax rates. The notes on specific companies beginning on page 62 add more details.

WHO’S PAYING CORPORATE TAXES — AND WHO’S NOT

On paper at least, the federal tax law requires corporations to pay 35 percent of their profits in federal income taxes. In fact, some of the 288 corporations in this study did pay close to the 35 percent official tax rate. But the vast majority paid considerably less. And some paid nothing at all. Over the five years covered by this study, the average effective tax rate (that is, the percentage of U.S. pretax profits paid in federal corporate income taxes) for all 288 companies was only 19.4 percent.

Overview:

The table on this page summarizes what the 288 companies paid (or didn’t pay) in effective U.S. income tax rates on their pretax U.S. profits.

- The good news is that 62 companies (about a fifth of the companies in this report), paid effective five year tax rates of more than 30 percent. Their average effective tax rate was 33.6 percent.

- The bad news is that even more companies, 67, paid effective five-year tax rates between zero and 10 percent. Their average effective tax rate was 1.5 percent.

- Even worse news is that 26 companies paid less than zero percent over the five-year period. Their effective tax rate averaged –5.1 percent.

A more detailed look:

Over the 2008-2012 period, five-year effective tax rates for the 288 companies ranged from a low of –33.0 percent for PEPCO Holdings to a high of 41.2 percent for St. Jude Medical. Here are some startling statistics:

- One hundred and eleven of the 288 companies paid zero or less in federal income taxes in at least one year from 2008 to 2012. Fifty-five of these companies enjoyed multiple no-tax years, bringing the total number of no tax years to 203. In the years they paid no income tax, these 111 companies earned $227 billion in pretax U.S. profits. But instead of paying $79 billion in federal income taxes, as the 35 percent corporate tax rate seems to require, these companies generated so many excess tax breaks that they reported negative taxes (often receiving tax rebate checks from the U.S. Treasury), totaling $28 billion. These companies’ “negative tax rates” mean that they made more after taxes than before taxes in those no-tax years.1

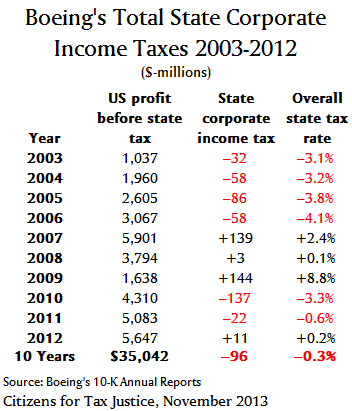

- Twenty six of these corporations paid less than nothing in aggregate federal income taxes over the 2008-12 period. These companies, whose pretax U.S. profits totaled $170 billion over the five years, included: Pepco Holdings (–33.0% tax rate), General Electric (–11.1%), Priceline.com (–3.0%), Ryder System (–4.7%), Verizon (–1.8%) and Boeing (–1.0%).

- In 2012, 43 companies paid no federal income tax, and got $2.9 billion in tax rebates. In 2011, 44 companies paid no income tax, and got $3.3 billion in rebates. (See Appendices with year-by-year results.)

- 119 of the 288 companies paid less than half the 35 percent statutory corporate tax rate for the five-year period as a whole. And more than two-thirds of the companies, 189 of the 288, paid effective tax rates of less than half the 35 percent statutory corporate income tax rate in at least one of the five years.

THE SIZE OF THE CORPORATE TAX SUBSIDIES

Over the 2008-12 period, the 288 companies earned more than $2.3 trillion in pretax profits in the United States. Had all of those profits been reported to the IRS and taxed at the statutory 35 percent corporate tax rate, then the 288 companies would have paid $816 billion in income taxes over the five years. But instead, the companies as a group paid just more than half of that amount. The enormous amount they did not pay was due to hundreds of billions of dollars in tax subsidies that they enjoyed.

- Tax subsidies for the 288 companies over the five years totaled a staggering $364 billion, including $56 billion in 2008, $70 billion in 2009, $80 billion in 2010, $87 billion in 2011, and $70 billion in 2012. These amounts are the difference between what the companies would have paid if their tax bills equaled 35 percent of their profits and what they actually paid.

- Almost half of the total tax-subsidy dollars over the five years — $173.7 billion — went to just 25 companies, each with more than $3.7 billion in tax subsidies.

- Wells Fargo topped the list of corporate tax-subsidy recipients, with nearly $21.6 billion in tax subsidies over the five years.

- Other top tax subsidy recipients included AT&T ($19.2 billion), IBM ($13.2 billion), General Electric ($12.7 billion), Verizon ($11.1 billion), Exxon Mobil ($8.7 billion), and Boeing ($7.4 billion).

TAX RATES (AND SUBSIDIES) BY INDUSTRY

The ffective tax rates in our study varied widely by industry. Over the 2008 12 period, effective industry tax rates (for our 288 corporations) ranged from a low of 2.9 percent to a high of 29.6 percent. In the year 2012 alone, the range of industry tax rates was even greater, from a low of –1.8 percent (a negative rate) up to a high of 28 percent.

- Gas and electric utility companies enjoyed the lowest effective federal tax rate over the five years, paying a tax rate of only 2.9 percent. This industry’s taxes declined steadily over the five years, from 12.8 percent in 2008 to –1.8 percent in 2012. These results were largely driven by the ability of these companies to claim accelerated depreciation tax breaks on their capital investments. Only one of the 27 utilities in our sample paid more than half the 35 percent statutory tax rate during the 2008-12 period.

- Other low-tax industries, paying less than half the statutory 35 percent tax rate over the entire 2008-12 period, included: industrial machinery (4.3%), telecommunications (9.8%), oil, gas & pipelines (14.4%), transportation (16.4%), and aerospace & defense (16.7%).

- None of the industries surveyed paid an effective tax rate of 30 percent or more over the full five-year period.

Effective tax rates also varied widely within industries. For example, over the five-year period, average tax rates on oil, gas & pipeline companies ranged from –2.4 percent for Apache Corporation up to 29.1 percent for HollyFrontier. Among aerospace and defense companies, five-year effective tax rates ranged from a low of –1.0 percent for Boeing up to a high of 29.5 percent for SAIC. Pharmaceutical giant Baxter paid only 3.5 percent, while its competitor Biogen Idec paid 32.9 percent. In fact, as the detailed industry table starting on page 32 of this report illustrates, effective tax rates were widely divergent in almost every industry.

Tax Subsidies by Industry:

We also looked at the size of the total tax subsidies received by each industry for the 288 companies in our study. Among the notable findings:

- 55 percent of the total tax subsidies went to just four industries: financial, utilities, telecommunications, and oil, gas & pipelines — even though these companies only enjoyed 39 percent of the U.S. profits in our sample.

- Other industries receive a disproportionately small share of tax subsidies. Companies engaged in retail and wholesale trade, for example, represented 16 percent of the five year U.S. profits in our sample, but enjoyed less than 6 percent of the tax subsidies.

It seems rather odd, not to mention highly wasteful, that the industries with the largest subsidies are ones that would seem to need them least. Regulated utilities, for example, make investment decisions in concert with their regulators based on needs of communities they serve. Oil and gas companies are so profitable that even President George W. Bush said they did not need tax breaks. He could have said the same about telecommunications companies. Financial companies get so much federal support that adding huge tax breaks on top of that seems unnecessary.

HISTORICAL COMPARISONS OF TAX RATES AND TAX SUBSIDIES

How do our results for 2008 to 2012 compare to corporate tax rates in earlier years? The answer illustrates how corporations have managed to get around some of the corporate tax reforms enacted back in 1986, and how tax avoidance has surged with the help of our political leaders.

By 1986, President Ronald Reagan fully repudiated his earlier policy of showering tax breaks on corporations. Reagan’s Tax Reform Act of 1986 closed tens of billions of dollars in corporate loopholes, so that by 1988, our survey of large corporations (published in 1989) found that the overall effective corporate tax rate was up to 26.5 percent, compared to only 14.1 percent in 1981-832. That improvement occurred even though the statutory corporate tax rate was cut from 46 percent to 34 percent as part of the 1986 reforms.3

In the 1990s, however, many corporations began to find ways around the 1986 reforms, abetted by changes in the tax laws as well as by tax-avoidance schemes devised by major accounting firms. As a result, in our 1996-98 survey of 250 companies, we found that their average effective corporate tax rate had fallen to only 21.7 percent. Our September 2004 study found that corporate tax cuts adopted in 2002 had driven the effective rate down to only 17.2 percent in 2002 and 2003. The five-year average rate found in the current study is only slightly higher, at 19.4 percent.

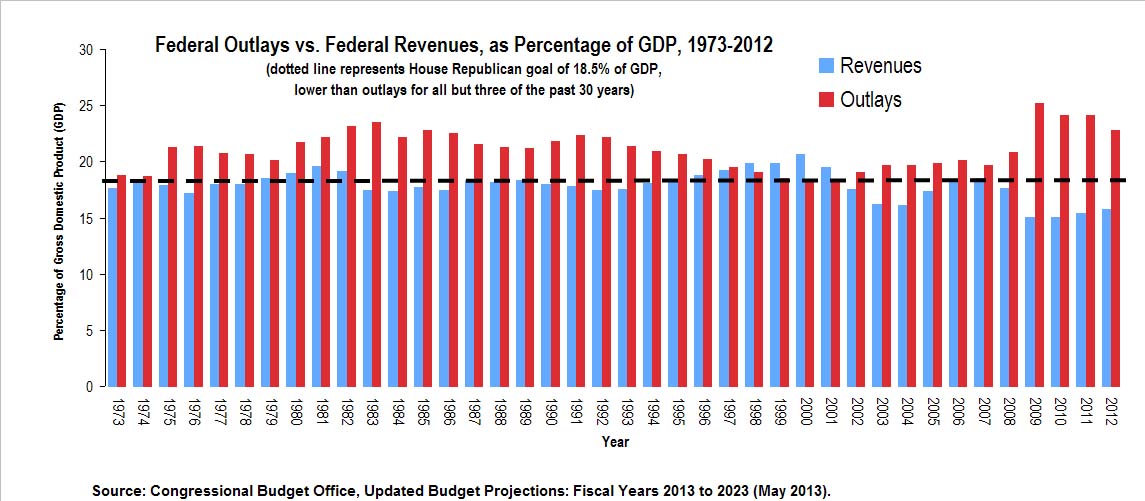

As a share of GDP, overall federal corporate tax collections in fiscal 2002 and 2003 fell to only 1.24 percent. At the time, that was their lowest sustained level as a share of the economy since World War II. Corporate taxes as a share of GDP recovered somewhat in the mid 2000s after the 2002-enacted tax breaks expired, averaging 2.3 percent of GDP from fiscal 2004 through fiscal 2008. But over the past five fiscal years (2009-13), total corporate income tax payments fell back to only 1.39 percent of the GDP.

Corporate taxes paid for more than a quarter of federal outlays in the 1950s and a fifth in the 1960s. They began to decline during the Nixon administration, yet even by the second half of the 1990s, corporate taxes still covered 11 percent of the cost of federal programs. But in fiscal 2012, corporate taxes paid for a mere 7 percent of the federal government’s expenses.

In this context, it seems odd that anyone would insist that corporate tax reform should be “revenue neutral.” If we are going to get our nation’s fiscal house back in order, increasing corporate income tax revenues should play an important role.

U.S. CORPORATE INCOME TAXES VS. FOREIGN INCOME TAXES

Corporate lobbyists relentlessly tell Congress that companies need tax subsidies from the government to be successful. They promise more jobs if they get the subsidies, and threaten economic harm if they are denied them. A central claim in the lobbyists’ arsenal is the assertion that their clients need still more tax subsidies to “compete” because U.S. corporate taxes are allegedly much higher than foreign corporate taxes. But the figures that most of these corporations report to their shareholders indicate the exact opposite, that they pay higher corporate income taxes in the other countries where they do business than they pay here in the U.S.

We examined the 125 companies in our survey that had significant pretax foreign profits (i.e., equal to at least 10 percent of their total worldwide pretax profits), and compared their 2008-12 U.S. (federal & state) effective tax rates to the foreign effective tax rates they paid. Here is what we found:

- About two-thirds (66 percent) of these U.S. companies paid higher foreign tax rates on their foreign profits than they paid in U.S. taxes on their U.S. profits.

- Overall, the effective foreign tax rate on the 125 companies was 2.7 percentage points higher than their U.S. effective tax rate.4

A table showing U.S. and foreign tax rates for each of the 125 companies begins on page 59.

How do these figures square with the well-known practice of corporations shifting their profits to countries like the Cayman Islands where they are not taxed at all? The figures here show what corporations report to their shareholders as U.S. profits and foreign profits, and therefore are likely to reflect profits genuinely earned in the U.S. and those genuinely earned offshore, respectively. But many of these corporations are likely to report something very different to the IRS by using various legal but arcane accounting maneuvers. Some of the profits correctly reported to shareholders as U.S. profits are likely to be reported to the IRS as profits earned in tax-haven countries like Bermuda or the Cayman Islands, where they are not taxed at all. Indeed, this partly explains the low effective U.S. income tax rates that many corporations enjoy. This “profit-shifting” problem will exist so long as our tax laws allow corporations to “defer” paying U.S. taxes on their “offshore” profits, providing an incentive to make U.S. profits appear to be earned in offshore tax havens.

The figures make clear that most American corporations are paying higher taxes in other countries where they engage in real business activities than they pay in U.S. taxes on their true U.S. profits.

One might note that paying higher foreign taxes to do business in foreign countries rather than in the United States has not stopped American corporations from shifting operations and jobs overseas over the past several decades. But this is just more evidence that corporate income tax levels are usually not a significant determinant of what companies do. Instead, companies have shifted jobs overseas for a variety of non-tax reasons, such as low wages and weaker labor and environmental regulations in some countries, a desire to serve growing foreign markets, and the development of vastly cheaper costs for shipping goods from one country to another than used to be the case.

HOW COMPANIES PAY LOW TAX BILLS

Why do we find such low tax rates on so many companies and industries? The company-by-company notes starting on page 62 detail, where available, reasons why particular corporations paid low taxes. Here is a summary of several of the major tax-lowering items that are revealed in the companies’ annual reports — plus some that aren’t disclosed.

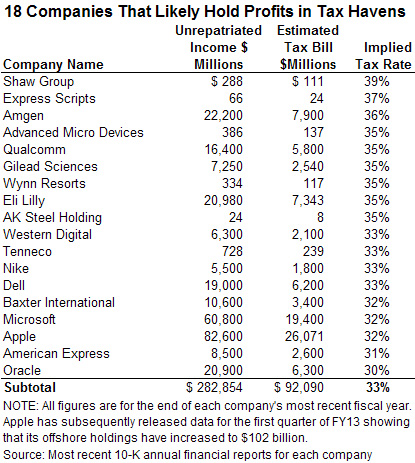

Offshore tax sheltering. The high-profile congressional hearings on tax dodging strategies of Apple and other tech companies over the past couple of years told lawmakers and the general public what some of us have been pointing out for years: multinational corporations and their accounting firms have become increasingly aggressive in seeking ways to shift their U.S. profits, on paper, to offshore tax havens to avoid their U.S. tax obligations. This typically involves various artificial transactions between U.S. corporations and their foreign subsidiaries, in which revenues are shifted to low- or no-tax jurisdictions (where these corporations are not actually doing any real business), while deductions are created in the United States.5

The cost of this tax-sheltering is difficult to determine precisely, but is thought to be enormous. In November 2010, the congressional Joint Committee on Taxation estimated that international corporate tax reforms proposed by Sen. Ron Wyden (D-Ore.) would increase U.S. corporate taxes by about $70 billion a year.6 Other analysts have pegged the cost of corporate offshore tax sheltering as even higher than that. Presumably, the effects of these offshore shelters in reducing U.S. taxes on U.S. profits are reflected in bottom-line U.S. corporate taxes reported in this study, even though companies do not directly disclose them.

Sadly, most Republicans in Congress, along with some Democrats, seem intent on making the problem of offshore tax sheltering even worse by replacing our current system, under which U.S. taxes on offshore profits are indefinitely “deferred,” with a so-called “territorial” system in which profits that companies can style as “foreign” are permanently exempt from U.S. taxes. This terrible approach, along with its cousin, a “repatriation holiday,” would encourage even more offshore tax avoidance.

Accelerated depreciation. The tax laws generally allow companies to write off their capital investments considerably faster than the assets actually wear out. This “accelerated depreciation” is technically a tax deferral, but so long as a company continues to invest, the tax deferral tends to be indefinite.

While accelerated depreciation tax breaks have been available for decades, temporary tax provisions have increased their cost in the past five years. In early 2008, in an attempt at economic stimulus for the flagging economy, Congress and President George W. Bush dramatically expanded depreciation tax breaks by creating a supposedly temporary “50 percent bonus depreciation” provision that allowed companies to immediately write off as much as 75 percent of the cost of their investments in new equipment right away.7 This provision was repeatedly extended and expanded through the end of 2013 under President Barack Obama. These changes to the depreciation rules, on top of the already far too generous depreciation deductions allowed under pre-existing law, certainly did reduce taxes for many of the companies in this study by tens of billions of dollars. But limited financial reporting makes it hard to calculate exactly how much of the tax breaks we identify are depreciation-related tax breaks.

Even without bonus depreciation, the tax law allows companies to take much bigger accelerated depreciation write-offs than is economically justified. This subsidy distorts economic behavior by favoring some industries and some investments over others, wastes huge amounts of resources, and has little or no effect in stimulating investment. A recent report from the Congressional Research Service, reviewing efforts to quantify the impact of depreciation breaks, found that “the studies concluded that accelerated depreciation in general is a relatively ineffective tool for stimulating the economy.”8

Combined with rules allowing corporations to deduct interest expenses, accelerated depreciation can result in very low, or even negative, tax rates on profits from particular investments. A corporation can borrow money to purchase equipment or a building, deduct the interest expenses on the debt and quickly deduct the cost of the equipment or building thanks to accelerated depreciation. The total deductions can then make the investments more profitable after-tax than before-tax.

Stock options. Most big corporations give their executives (and sometimes other employees) options to buy the company’s stock at a favorable price in the future. When those options are exercised, companies can take a tax deduction for the difference between what the employees pay for the stock and what it’s worth9. Paying executives with options took off in the mid 1990s, in part because this kind of compensation was exempt from a law enacted in 1993 that tried to reduce income inequality by limiting corporate deductions for executive pay to $1 million per top executive.

Stock options were also attractive because companies didn’t have to reduce the profits they report to their shareholders by the amount that they deducted on their tax returns as the “cost” of the stock options. Many people complained (rightly) that it didn’t make sense for companies to treat stock options inconsistently for tax purposes versus shareholder-reporting or “book” purposes. Some of us argued that this noncash “expense” should not be deductible for either tax or book purposes. We didn’t win that argument, but nevertheless, as a result of the complaints about inconsistency, rules in place since 2006 now require companies to lower their “book” profits to take some account of options. But the book write-offs are still usually considerably less than what the companies take as tax deductions. That’s because the oddlydesigned rules require the value of the stock options for book purposes to be calculated — or guessed at — when the options are issued, while the tax deductions reflect the actual value when the options are exercised. Because companies low-ball the estimated values for book purposes, they usually end up with bigger tax deductions than they deduct from the profits they report to shareholders.10

Some members of Congress have taken aim at this remaining inconsistency. In February of 2013, Senator Carl Levin (D-MI) introduced the “Cut Unjustified Loopholes Act,” which includes a provision requiring companies to treat stock options the same for both book and tax purposes, as well as making stock option compensation subject to the $1 million cap on corporate tax deductions for top executives’ pay. Levin calculates that over the past five years U.S. companies have consistently taken far higher stock-option tax write-offs than they reported as book expenses.

Of our 288 corporations, 204 fully disclosed their “excess stock-option tax benefits” for at least one year in the 2008-12 period, which lowered their taxes by a total of $27.1 billion over five years. (Some other companies enjoyed stock option benefits, but did not disclose them fully.) The tax benefits ranged from as high as $1.6 billion for Goldman Sachs over the five years to only tiny amounts for a few companies. Just 25 companies enjoyed 55 percent of the total excess tax benefits from stock options disclosed by all of our 288 companies, getting $15.3 billion of the $27.1 billion total.

|

SOME COMPANIES ZEROED OUT While most of the companies in our |

Industry-specific tax breaks. The federal tax code also provides tax subsidies to companies that engage in certain activities. For example: research (very broadly defined); drilling for oil and gas; providing alternatives to oil and gas; making video games; ethanol production; maintaining railroad tracks; building NASCAR race tracks; making movies; and a wide variety of activities that special interests have persuaded Congress need to be subsidized through the tax code.

One of these special interest tax breaks is of particular importance to long-time tax avoider General Electric. It is oxymoronically titled the “active financing exception” (the joke is that financing is generally considered to be a quintessentially passive activity). This tax break allows financial companies (GE has a major financial branch) to pay no taxes on foreign (or ostensibly foreign) lending and leasing, apparently while deducting the interest expenses of engaging in such activities from their U.S. taxable income. (This is an exception to the general rule that U.S. corporations can defer their U.S. taxes on offshore profits only if they take the form of active income rather than passive income.) This tax break was repealed in 1986, which helped put GE back on the tax rolls. But the tax break was reinstated, allegedly “temporarily,” in 1997, and has been periodically extended ever since, at a current cost of more than $5 billion a year. We don’t know how much of this particular tax subsidy goes to GE, but in its annual report, GE singles out the potential expiration of the “active financing” loophole as one of the significant “Risk Factors” the company faces.11

Notably, the “active financing” loophole is one of dozens of narrowly targeted temporary tax giveaways that expired at the end of calendar year 2013. These tax breaks, known collectively as the “extenders,” have been routinely renewed temporarily for decades. If Congressional tax writers could restrain them-selves from passing a new “extenders” bill that brings the active financing loophole back to life — that is, if Congress could simply do nothing on this front — that would constitute a major step forward toward corporate tax fairness.

|

“MANUFACTURING” DOES NOT MEAN WHAT YOU THINK IT MEANS When Congressional tax writers signaled their intention to enact a new tax break for domestic manufacturing income in 2004, lobbyists began a feeding frenzy to define both “domestic” and “manufacturing” as expansively as possible. As a result, current beneficiaries of the tax break include mining and oil, coffee roasting (a special favor to Starbucks, which lobbied heavily for inclusion) and even Hollywood film production. The Walt Disney corporation has disclosed receiving $720 million in tax breaks from this provision over the past five years, presumably from its film production work. World Wrestling Entertainment has disclosed receiving tax breaks for its “domestic manufacturing” of wrestling-related films. And we were surprised to find that Silicon Valley-based OpenTable, which “manufactures” only online restaurant reservations, has somehow found a way to claim this tax break. President Obama has sensibly proposed scaling back the domestic manufacturing deduction to prevent big oil and gas companies from claiming it, but a better approach would be to simply repeal this tax break. At a minimum, Congress and the Obama Administration should take steps to ensure that the companies claiming this misguided giveaway are engaged in something that can at least plausibly be described as manufacturing |

Details about companies that used specific tax breaks to lower their tax bills — often substantially — can be found in the company-by-company notes.

What about the AMT? The corporate Alternative Minimum Tax (AMT) was revised in 1986 to ensure that profitable corporations pay some substantial amount in income taxes no matter how many tax breaks they enjoy under the regular corporate tax. The corporate AMT (unlike the much maligned personal AMT) was particularly designed to curb leasing tax shelters that had allowed corporations such as General Electric to avoid most or all of their regular tax liabilities.

But laws enacted in 1993 and 1997 at the behest of corporate lobbyists sharply weakened the corporate AMT, and now hardly any companies pay the tax. In fact, many are getting rebates for past AMT payments. In late 2001, U.S. House of Representatives leaders attempted to repeal the corporate AMT entirely and give companies instant refunds for any AMT they had paid since 1986. Public outcry stopped that outrageous plan, but the AMT remains a shell of its former self that will require substantial reform if it is to once again achieve its goal of curbing corporate tax avoidance.

WHO LOSES FROM CORPORATE TAX AVOIDANCE?

Low- and no-tax companies may be happy about their ability to avoid huge amounts in taxes every year, but our current corporate income tax mess is not good for the rest of us. The losers under this system include:

The general public. As a share of the economy, corporate tax payments have fallen dramatically over the last quarter century. So one obvious group of losers from growing corporate tax avoidance is the general public, which has to pay more for — and/or get less in — public services, or else face mounting national debt burdens that must be paid for in the future.

Disadvantaged companies. Almost as obvious is how the wide variation in tax rates among industries, and among companies within particular industries, gives relatively high-tax companies and industries a legitimate complaint that federal tax policy is helping their competitors at their expense. The table on page 7 showed how widely industry tax rates vary. The detailed industry tables starting on page 32 show that discrepancies within industries also abound. For example:

- Honeywell International and Deere both produce industrial machinery. But over the 2008-12 period, Deere paid 29.8 percent of its profits in U.S. corporate income taxes, while Honeywell paid a tax rate of only 7.5 percent.

- Aerospace giant Boeing paid a five-year federal tax rate of –1.0 percent, while competitor General Dynamics paid 29.0 percent.

- Household products maker Kimberly-Clark paid a five-year rate of 13.9 percent, while competitor Clorox paid 28.6 percent.

- Pharmaceutical firm Baxter International paid just 5.6 percent of its five year U.S. profits in federal income taxes, while Becton Dickinson paid 23.5 percent.

- Time Warner Cable paid 3.9 percent over five years, while its competitor Comcast paid 24.0 percent.

The U.S. economy. Besides being unfair, the fact that the government is offering much larger tax subsidies to some companies and industries than others is also poor economic policy. Such a system artificially boosts the rate of return for tax-favored industries and companies and reduces the rate of return for those industries and companies that are less favored. To be sure, companies that push for tax breaks argue that the “incentives” will encourage useful activities. But the idea that the government should tell businesses what kinds of investments to make conflicts with our basic economic philosophy that consumer demand and free markets should be the test of which private investments make sense.

To be sure, most of the time, tax breaks don’t have much effect on business behavior. After all, companies don’t lobby to have the government tell them what to do. Why would they? Instead, they ask for subsidies to reward them for doing what they would do anyway. Thus, to a large degree, corporate tax subsidies are simply an economically useless waste of resources.

Indeed, corporate executives (as opposed to their lobbyists) often insist that tax subsidies are not the basis for their investment decisions. Other things, they say, usually matter much more, including demand for their products, production costs and so forth.

But not all corporate tax subsidies are merely useless waste. Making some kinds of investments more profitable than others through tax breaks will sometimes shift capital away from what’s most economically beneficial and into lower-yield activities. As a result, the flow of capital is diverted in favor of those industries that have been most aggressive in the political marketplace of Washington, D.C., at the expense of long-term economic growth.

State governments and state taxpayers. The loopholes that reduce federal corporate income taxes cut state corporate income taxes, too, since state corporate tax systems generally take federal taxable income as their starting point in computing taxable corporate profits.12Thus, when the federal government allows corporations to write off their machinery faster than it wears out or to shift U.S. profits overseas or to shelter earnings from oil drilling, most states automatically do so, too. It’s a mathematical truism that low and declining state revenues from corporate income taxes means higher state taxes on other state taxpayers or diminished state and local public services.

The integrity of the tax system and public trust therein. Ordinary taxpayers have a right to be suspicious and even outraged about a tax code that seems so tilted toward politically well-connected companies. In a tax system that by necessity must rely heavily on the voluntary compliance of tens of millions of honest taxpayers, maintaining public trust is essential — and that trust is endangered by the specter of widespread corporate tax avoidance. The fact that the law allows America’s biggest companies to shelter almost half of their U.S. profits from tax, while ordinary wage earners have to report every penny of their earnings, has to undermine public respect for the tax system.

A PLEA FOR BETTER DISCLOSURE

Determining tax rates paid by the nation’s biggest and most profitable corporations shouldn’t be hard. Lawmakers, the media and the general public should all have a straightforward way of knowing whether our tax system requires companies like General Electric to pay their fair share. But in fact, it’s an incredibly difficult enterprise. Even veteran analysts struggle to understand the often cryptic disclosures in corporate annual reports. And many amateurs come up with (and unfortunately publish) hugely mistaken results. The fact that it took us so much time and effort to complete this report illustrates how desirable it would be if companies would provide the public with clearer and more detailed information about their federal income taxes.

We need a straightforward statement of what they paid in federal taxes on their U.S. profits, and the reasons why those taxes differed from the statutory 35 percent corporate tax rate. This information would be a major help, not only to analysts but also to policy makers.

TAX REFORM (& DEFORM) OPTIONS

More than a quarter century after major loophole-closing corporate tax reforms were enacted under Ronald Reagan in 1986, many of the problems that those reforms were designed to address have re-emerged — along with a dizzying array of new corporate tax-avoidance techniques. But these problems can be resolved. The discussion of tax giveaways elsewhere in this report provides a clear roadmap to the types of reforms lawmakers should consider:

- Repealing the rule allowing U.S. corporations to “defer” their U.S. taxes on their offshore profits so there would be no tax incentive to shift profits to offshore tax havens or jobs to lower-tax countries.

- Limiting the ability of tech and other companies to use executive stock options to reduce their taxes by generating phantom “costs” these companies never actually incur.

- Having sensibly allowed “bonus depreciation” to expire at the end of 2013, Congress could take the next step and repeal the rest of accelerated depreciation, too.

- Reinstating a strong corporate Alternative Minimum Tax that really does the job it was originally designed to do.

- Require more complete and transparent geography-specific public disclosure of corporate income and tax payments than the Securities and Exchange Commission’s regulations currently mandate (see page 19).

Sadly, these sensible proposals bear little resemblance to the “reform” ideas put forth by some members of Congress. Corporate tax legislation now being promoted by many on Capitol Hill seems fixated on the misguided notion that as a group, corporations are now either paying the perfect amount in federal income taxes or are paying too much. Many members of the tax writing committees in Congress seem intent on making changes that would actually make it easier (and more lucrative) for companies to shift taxable profits, and potentially jobs, overseas.13

Real, revenue-raising corporate tax reform, however, is what most Americans want and what our country needs.14 Our elected officials should stop kowtowing to the loophole lobbyists and stand up for the vast majority of Americans.

YEAR-BY-YEAR DETAILS ON COMPANIES PAYING NO INCOME TAXES:

APPENDIX 1:

Why the “current” federal income taxes that corporations disclose in their annual reports are the best (and only) measure of what corporations really pay (or don’t pay) in federal income tax

Some analysts and journalists, along with some corporations, have complained that the “current income taxes” reported by corporations under oath in their annual reports are not a true measure of the income taxes that corporations actually pay. This complaint is mostly incorrect. In fact, “current income taxes,” with a sometimes important downward adjustment that we make for “excess stock option tax benefits,” are a good assessment of companies’ tax situations, and are the only available measure of what corporations pay in income taxes broken down by payments to the federal government, state governments and foreign governments.

Our report focuses on the federal income tax that companies are currently paying on their U.S. profits. So we look at the current federal tax expense portion of the income tax provision in the financial statements. The “deferred” portion of the tax provision is tax based on the current year income but not due yet because of the differences between calculating income for financial statement purposes and for tax purposes. When those timing differences turn around, if they ever do, the related taxes will be reflected in the current tax expense.15

The federal current tax expense is just exactly what the company expects its current year tax bill to be when it files its tax return. If the calculation of the income tax provision was done perfectly, the current tax expense (after adjusting for excess stock option tax benefits) would exactly equal the total amount of tax shown on the tax return. But the income tax provision is calculated in February as the company is preparing its 10-K for filing with the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), and the company’s tax return isn’t usually filed until September. While the company’s tax return is prepared over those several months, things will be found that weren’t accounted for in the financial statement income tax provision, and numbers that were estimated in February will be refined for the actual return. Those small differences will be included in the following year’s current tax expense, but the impact on our calculations is minimal (especially because we look at the rates over a period of years). If the differences in any one year were material, accounting rules would require the company to restate their prior year financials.

The complaints that “current income taxes” are not an accurate measure of taxes actually paid make two main points:

- Excess stock option tax benefits:The first, easily dismissed complaint is that “current income taxes” do not include some of the tax benefits that corporations enjoy when employees exercise stock options. That is certainly true. But our study does subtract those “excess stock option tax benefits” from current income taxes in the tax results we report.

- Dubious tax benefits:A more interesting, but also flawed argument against the use of current income taxes (less stock option tax benefits) involves the accounting treatment of dubious tax benefits that companies claim on their tax returns but are not allowed to report on their books until and if these claimed tax benefits are allowed.

Dubious tax benefits, officially known as “uncertain tax positions” and “unrecognized tax benefits,” are tax reductions that corporations claim when they file their tax returns but which they expect the IRS (or other taxing authority) to disallow.

For example, suppose a corporation on its 2008 tax return tells the IRS that it owes $700 million in federal income tax for the year. But the corporation’s tax staff believes that on audit, the corporation will most likely owe an additional $300 million, because $300 million in tax benefits that the company claimed on its tax return are unlikely to be approved by the IRS. As a result, the corporation’s current income tax for 2008 that it reports to shareholders (and that we calculate in our reports) will be $1,000 million, the amount that the corporation expects to actually owe in income taxes.16

After that, two things, in general, can happen:

- More often than not.Suppose that, as the corporation’s tax staff predicted, the IRS in 2012 disallows the $300 million in dubious tax benefits claimed on the company’s 2008 tax return. In this case, the $1,000 million in reported current income tax for 2008 will turn out to have been correct. In

2012, when the dubious tax benefits are disallowed, the company will have to pay back the $300 million (plus interest and penalties) to the IRS. Reasonably enough, the corporation will not report that 2012 payback in its 2012 annual report to shareholders, since it had already reported it as paid back in 2008.

- Occasionally.Suppose instead that to the surprise of the corporation’s tax staff, the IRS in 2012 allows some or part of the $300 million in dubious tax benefits claimed back in 2008. In this case, the corporation will reduce its 2012 “current income tax” reported to shareholders by the allowed amount of the dubious tax benefits previously claimed on the corporation’s 2008 tax return. But, argue some analysts, isn’t the right answer to go back and reassign the eventually allowed dubious tax benefits to 2008, the year they were claimed on the corporation’s tax return? The answer is no, for two reasons:

First, booking the corporation’s tax windfall in 2012, the year it was allowed by the IRS makes logical sense. That’s because until the IRS allowed the dubious tax benefits, it was the judgment of the company’s tax experts that the company was probably not legally entitled to those tax benefits. In essence, the IRS’s allowance of all or part of the dubious tax benefits claimed on the company’s 2008 tax return is the same as the corporation receiving an unexpected tax refund in 2012.

It’s as if the company had initially borrowed the money from the IRS, but expected to pay it back (with interest). When and if the IRS “forgives” part or all of the “loan,” then the company recognizes the tax benefit. Likewise, suppose you borrow money from you employer with the expectation that you’ll pay it back. But later, your employer forgives your debt. You didn’t have to declare the loan as income when you borrowed the money, but you do have to declare it as income when the loan is forgiven.

Second, even if one believed that the 2012 tax windfall ought to be reassigned to 2008, there is simply no way to do so. That’s because corporations do not disclose sufficient information in their annual reports to make such a retroactive reallocation.17

- A final point here, regarding a potentially useful measure called “cash income taxes paid”:

In their annual reports to shareholders, corporations also report something called “cash income taxes paid.” Cash income taxes paid is net of stock option tax benefits and does not include “deferred” taxes.18 Unlike current taxes, however, cash income taxes paid subtracts dubious tax benefits that are likely to be reversed later (and adds those dubious tax benefits if and when they are later reversed).

“Cash income taxes paid” is sometimes interesting, but it is useless for purposes of measuring the federal income taxes that U.S. multinational corporations pay on their U.S. profits. That’s because “cash income taxes paid” are not broken down by taxing jurisdiction. Instead, this measure lumps together U.S. federal income taxes, U.S. state income taxes, and foreign income taxes. Since most big corporations are multinationals these days, and almost all are subject to both federal and state income taxes, that’s a fatal defect.19

Even for purely domestic corporations, “cash income taxes paid” is a problematic measure. It often fails to match income in a given year with the taxes paid for that year (since companies don’t settle up with the IRS until after a given year is over). The cash payments made during the year include quarterly estimated tax payments for the current year, balances due on tax returns for prior years, and any refunds or additional taxes due as a result of tax return examinations or loss carrybacks.

To be sure, if “cash income taxes paid” were reported by taxing jurisdiction and better linked with the pretax income in a given year, then this measure could be useful. But as of now, it is not, except in one way: it supports our use of current taxes as a measure of how much in taxes corporations are really paying. If you compare a company’s total current taxes (after subtracting the excess stock benefits) to cash taxes paid over a period of years, you will see that they are generally very close. The differences, if any, suggest that the effective rate corporations are paying may be even less than what we’ve calculated.

APPENDIX 2:

Seventeen multinational corporations that do not provide plausible geographic breakdowns of their pretax profits

Noticeably missing from our sample of 288 profitable companies are some well-known multinational corporations, such as Apple and Microsoft. They are excluded because we do not believe the geographic breakdown of their profits between the U.S. and foreign countries that they report to shareholders.

For multinational companies, we are at the mercy of companies accurately allocating their pretax profits between U.S. and foreign in their annual reports. Hardly anyone but us cares about this geographic book allocation, yet fortunately for us, it appears that the great majority of companies were reasonably honest about it. Even companies that are shifting U.S. profits to offshore tax havens generally do not make the implausible claim to their shareholders that such U.S. profits were actually “foreign.”

Some companies, however, report geographic profit allocations that we find to be obviously ridiculous. Indicators of ridiculousness include:

- A company reports that all or even more than all of its pretax profits were foreign, even though most of its revenues and assets are in the United States.

- A company reports U.S. taxes that are a very high share of what it calls its U.S. profits, while its foreign taxes are a very low share of what it calls its foreign profits.

- A company admits that it has used tax schemes to move profits to low- or no-tax jurisdictions.

- A company has a large amount of “unrecognized tax benefits” relative to the current income taxes it reports. These “UTBs” are tax reductions that companies have claimed on their tax returns but do not expect to be allowed when their returns are audited (and are thus not allowed to be reported as tax savings to their shareholders). A substantial portion of UTBs involve schemes to shift profits to tax havens.

In our previous corporate studies, we generally left out such suspicious companies. In a few cases, with grave reservations, we included some potential “liar companies” that we highly suspected made a lot more in the U.S. and less overseas than they reported to their shareholders.

In our current report, we have done better. We have left out of our main analysis 17 companies whose geographic allocations we do not trust (and that we highly suspect have shifted a significant portion of their U.S. profits, on paper, into tax havens). We have included in this appendix some information on these 17 companies. In a table on this page, we show the worldwide pretax profits for these suspicious companies over the 2008-12 period, along with their worldwide income taxes and worldwide effective tax rates.

Here are some of the specific reasons why we are suspicious of the 17 multinational companies we excluded from our main study:

- Abbott Laboratories says that only 3 percent of its 2008-12 pretax profits were earned in the United States, despite the fact that it says 44 percent of its revenues were in the U.S. The company also says that its current U.S. federal and state income tax rate on that tiny share of its profits was 276 percent! In contrast, Abbott says its foreign current tax rate on its purported foreign profits was only 15.5 percent.

- Amgen says that only 40 percent of its profits were earned in the U.S., despite the fact that it says 78 percent of its revenues were in the U.S. It claims to have paid a 31.4 percent tax rate in the U.S. on its U.S. profits, while paying a mere 5.2 percent tax rate on its foreign profits.

- Apple claims to have paid a 36.5 percent U.S. tax rate on its claimed U.S. profits, but only 3.4 percent on its foreign profits. The low “foreign” rate mainly reflects the fact that Apple, for tax purposes, has moved about two thirds of its worldwide profits to Ireland, where those profits are taxed neither by Ireland nor by the U.S. or any other government.

- Broadcom claims to have lost money in the United States over the 2008-12 period. On the profits it says were “foreign,” it claims to have paid a foreign tax rate of only 2.8 percent.

- Celgene says that 61 percent of its revenues were in the U.S., but only 24 percent of its profits were U.S. Using Celgene’s breakdown of profit, its U.S. tax rate on U.S. profits would be 35.1 percent, while its foreign tax rate on “foreign” profits would be only 4.5 percent.

- Cisco says that its U.S. taxes were 79 percent of its U.S. profits, while its foreign tax rate was a mere 6.5 percent.

- Dell says it earned only 11 percent of its pretax profits in the U.S., even though it reports that U.S. revenues were more than half of its worldwide total. Dell’s reported U.S. tax rate on what it claims were its U.S. profits was 175 percent. In contrast, its reported foreign tax rate on foreign profits was a mere 6.9 percent.

- eBay claims to have paid a U.S. tax rate of 42.3 percent on its U.S. profits, while paying only a 4.8 percent foreign tax rate on its purported foreign profits. (eBay says only a quarter of its worldwide profits were earned in the U.S., even though it says half of its revenues were in the U.S.).

- EMC claims to have paid a 23.9 percent U.S. tax rate on its claimed U.S. profits, versus a foreign tax rate on foreign profits of only 7.8 percent.

- Gilead Sciences claims to have paid a 33.5 percent U.S. tax rate on its U.S. profits, versus a foreign tax rate of only 3.2 percent.

- Google claims to have paid a U.S. tax rate of 47.4 percent, versus a foreign tax rate of only 3.3 percent.

- Johnson & Johnson says it paid a U.S. tax rate of 39.3 percent, versus a foreign tax rate of 14.2 percent. In its annual report, the company mentions some of the profit-shifting techniques it uses, such as its “intangible assets in low tax jurisdictions” and “the CFC look-through provisions,” which can allow companies to create “nowhere income,” untaxed by any government.

- Medtronic told its shareholders that only a third of its profits were earned in the U.S., even though three-fifths of its revenues are in the U.S. It says its U.S. taxes were 30.9 percent of its U.S. profits, while its foreign taxes were 10.5 percent of its foreign profits.

- Microsoft says that only a quarter of its profits are in the U.S., even though it says that more than half its revenues are in the U.S. Microsoft would like us to believe that its U.S. tax rate on its U.S. profits was 47.5 percent, while it foreign tax rate on foreign profits was only 8.8 percent.

- NetApp claims to have paid a 32.3 percent tax rate on its U.S. profits, but only 5.9 percent on its purported foreign profits. It says that half of its revenues are in the U.S., but only a sixth of its profits.

- Western Digital claims to have paid a U.S. tax rate of 31.9 percent, versus a foreign tax rate of only 2.1 percent.

- Western Union claims a U.S. tax rate of 57.9 percent on its U.S. profits, versus a foreign tax rate of only 6.0 percent.

METHODOLOGY

This study is an in-depth look at corporate taxes over the past five years. It is similar to a series of widely-cited and influential studies by Citizens for Tax Justice and the Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, starting in the 1980s and most recently in 2011. The new report covers 288 large Fortune 500 corporations, and analyzes their U.S. profits and corporate income taxes from 2008 to 2012. Over the five-year period, these companies reported $2.3 trillion in pretax U.S. profits, and, on average, paid tax on just over half that amount.

- Choosing the Companies:

Our report is based on corporate annual reports to shareholders and the similar 10-K forms that corporations are required to file with the Securities and Exchange Commission. We relied on electronic versions of these reports from the companies’ web sites or from the SEC web site.

As we pursued our analysis, we gradually eliminated companies from the study based on two criteria: either (1) a company lost money in any one of the five years; or (2) a company’s report did not provide sufficient information for us to accurately determine its domestic profits, current federal income taxes, or both. This left us with the 288 companies in our report.

Some companies did not report data for all of the five years between 2008 and 2012, either because their initial public offering occurred after 2008 or because they were spun off of parent companies after 2008. We included these companies in the sample only if they reported data for at least 3 of the 5 years.

The total net federal income taxes reported by our 288 companies over the five years amounted to 43 percent of all net federal corporate income tax collections in that period.

- Method of Calculation

Conceptually, our method for computing effective corporate tax rates was straightforward. First, a company’s domestic profit was determined and then current state and local taxes were subtracted to give us net U.S. pretax profits before federal income taxes. (We excluded foreign profits since U.S. income taxes rarely apply to them, because the taxes are indefinitely “deferred” or are offset by credits for taxes paid to foreign governments.) We then determined a company’s federal current income taxes. Current taxes are those that a company is obligated to pay during the year; they do not include taxes “deferred” due to various federal “tax incentives” such as accelerated depreciation. Finally, we divided current U.S. taxes by pretax U.S. profits to determine effective tax rates.1

- Issues in measuring profits.

The pretax U.S. profits reported in the study are generally as the companies disclosed them. In a few cases, if companies did not separate U.S. pretax profits from foreign, but foreign profits were obviously small, we made our own geographic allocation, based on a geographic breakdown of operating profits minus a prorated share of any expenses not included therein (e.g., overhead or interest), or we estimated foreign profits based on reported foreign taxes or reported foreign revenues as a share of total worldwide profits.

Many companies report “noncontrolling interest” income, which is usually included in total reported pretax income. This is income of a subsidiary that is not taxable income of the parent company. When substantial noncontrolling income was disclosed, we subtracted it from US and/or foreign pretax income.

Where significant, we adjusted reported pretax profits for several items to reduce distortions. In the second half of 2008, the U.S. financial system imploded, taking our economy down with it. By the fourth quarter of 2008, no one knew for sure how the federal government’s financial rescue plan would work. Many banks predicted big future loan losses, and took big book write-offs for these pessimistic estimates. Commodity prices for things like oil and gas and metals plummeted, and many companies that owned such assets booked “impairment charges” for their supposed long-term decline in value. Companies that had acquired “goodwill” and other “intangible assets” from mergers calculated the estimated future returns on these assets, and if these were lower than their “carrying value” on their books, took big book “impairment charges.” All of these book write-offs were non-cash and had no effect on either current income taxes or a company’s cash flow.

As it turned out, the financial rescue plan, supplemented by the best parts of the economic stimulus program adopted in early 2009, succeeded in averting the Depression that many economists had worried could have happened. Commodity prices recovered, the stock market boomed, and corporate profits zoomed upward. But in one of the oddities of book accounting, the impairment charges could not be reversed.

Here is how we dealt with these extraordinary non-cash charges, plus “restructuring charges,” that would otherwise distort annual reported book profits and effective tax rates:

- Smoothing adjustments

Some of our adjustments simply reassign booked expenses to the year’s that the expenses were actually incurred. These “smoothing” adjustments avoid aberrations in one year to the next.

- “Provisions for loan losses”by financial companies: Rather than using estimates of future losses, we generally replaced companies’ projected future loan losses with actual loan charge-offs less recoveries. Over time, these two approaches converge, but using actual loan charge-offs is more accurate and avoids year-to-year distortions. Typically, financial companies provide sufficient information to allow this kind of adjustment to be allocated geographically.

- “Restructuring charges”:Sometimes companies announce a plan for future spending (such as the cost of laying off employees over the next few years) and will book a charge for the total expected cost in the year of the announcement. In cases where these restructuring charges were significant and distorted year-by-year income, we reallocated the costs to the year the money was actually spent (allocated geographically).

- “Impairments”

Companies that booked “impairment” charges typically went to great lengths to assure investors and stock analysts that these charges had no real effect on the companies’ earnings. Some companies simply excluded impairment charges from the geographic allocation of their pretax income. For example, Conoco-Phillips assigned its 2008 pretax profits to three geographic areas, “United States,” “Foreign,” and “Goodwill impairment,” implying that the goodwill impairment charge, if it had any real existence at all, was not related to anything on this planet. In addition, many analysts have criticized these non-cash impairment charges as misleading, and even “a charade.”2 Here is how we treated “impairment charges.”

- Impairment charges for goodwill (and intangible assets with indefinite lives) do not affect future book income, since they are not amortizable over time. We added these charges back to reported profits, allocating them geographically based on geographic information that companies supplied, or as a last resort by geographic revenue shares.

- Impairment charges to assets (tangible or intangible) that are depreciable or amortizable on the books will affect future book income somewhat (by reducing future book write-offs, and thus increasing future book profits). But big impairment charges still hugely distort current year book profit. So as a general rule, we also added these back to reported profits if the charges were significant.

- Caveat: Impairments of assets held for sale soon were not added back.

All significant adjustments to profits made in the study are reported in the company-by-company notes.

- Issues in measuring federal income taxes.

The primary source for current federal income taxes was the companies’ income tax notes to their financial statements. From reported current taxes, we subtracted “excess tax benefits” from stock options (if any), which reduced companies’ tax payments but which are not reported as a reduction in current taxes, but are instead reported separately (typically in companies’ cash-flow statements). We divided the tax benefits from stock options between federal and state taxes based on the relative statutory tax rates (using a national average for the states). All of the non-trivial tax benefits from stock options that we found are reported in the company-by-company notes.

- Negative tax rates :

A “negative” effective tax rate means that a company enjoyed a tax rebate. This can occur by carrying back excess tax deductions and/or credits to an earlier year or years and receiving a tax refund check from the U.S. Treasury Department. Negative tax rates can also result from recognition of tax benefits claimed on earlier years’ tax returns, but not reported as tax reduction in earlier annual reports because companies did not expect that the IRS would allow the tax benefits. If and when these “uncertain tax benefits” are recognized, they reduce a companies reported current income tax in the year that they are recognized. See the appendix on page 25 for a fuller discussion of “uncertain tax benefits.”

- High effective tax rates:

Ten of the companies in our study report effective five-year U.S. federal income tax rates that are slightly higher than the 35 percent official corporate tax rate. Indeed, in particular years, some companies report effective U.S. tax rates that are much higher than 35 percent. This phenomenon is usually due to taxes that were deferred in the past but that eventually came due. Such “turnarounds” often involve accelerated depreciation tax breaks, which usually do not turn around so long as companies are continuing to increase or maintain their investments in plant and equipment. But these tax breaks can turn around if new investments fall off (for example, because a bad economy makes continued new investments temporarily unprofitable).

- Industry classifications:

Because some companies do business in multiple industries, our industry classifications are far from perfect. We generally, but not always, based them on Fortune’s industry classifications.

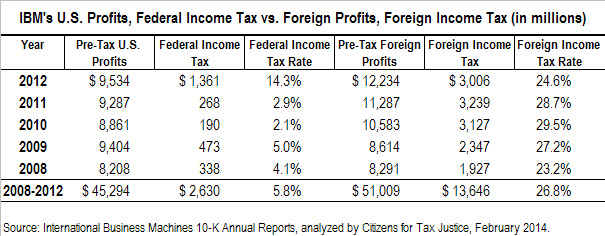

engage in accounting gimmicks to make most of its U.S. profits appear (to the IRS) to be earned in subsidiaries in Bermuda, the Cayman Islands or other countries that do not tax these profits. Of course, IBM does little or no real business in these countries and its subsidiaries there may be nothing more than post office boxes.

engage in accounting gimmicks to make most of its U.S. profits appear (to the IRS) to be earned in subsidiaries in Bermuda, the Cayman Islands or other countries that do not tax these profits. Of course, IBM does little or no real business in these countries and its subsidiaries there may be nothing more than post office boxes.

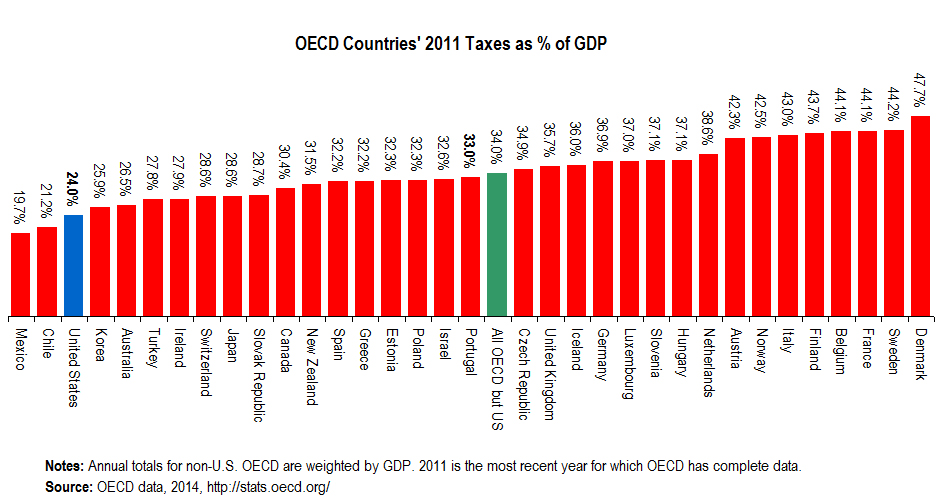

graph above, in 2011, the most recent year for which there is complete data, the U.S. collected less tax revenue as a percentage of its economy than did any other OECD country except for Chile and Mexico.

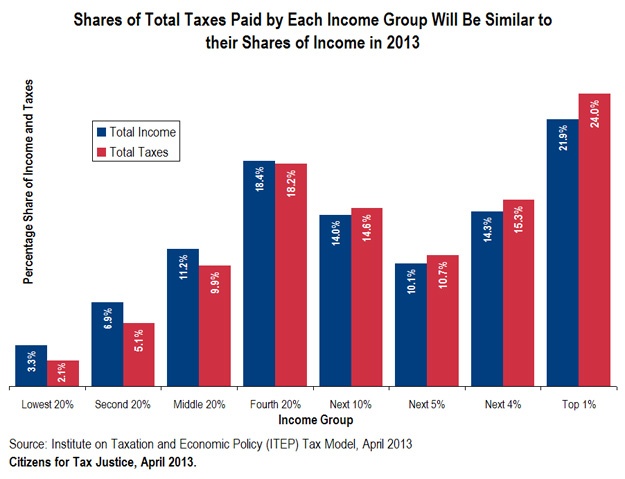

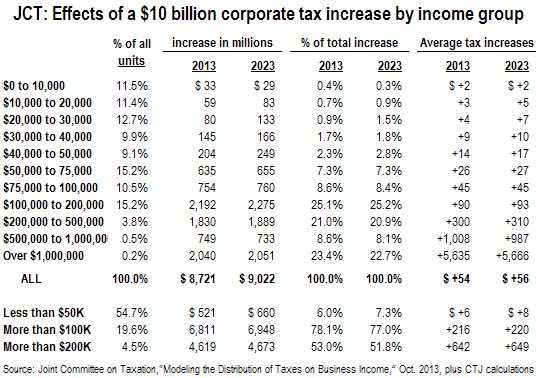

graph above, in 2011, the most recent year for which there is complete data, the U.S. collected less tax revenue as a percentage of its economy than did any other OECD country except for Chile and Mexico. The Treasury Department and the Joint Committee on Taxation (JCT) have recently confirmed that the corporate income tax is a progressive tax. It is clear that the corporate tax is, in the short-term, borne by the (mostly wealthy) owners of capital — meaning it’s paid by the owners of corporate stocks and other business and investment assets because the tax reduces what corporations can pay out as dividends to their shareholders. The Treasury Department concluded that even in the long-run, 82 percent of the tax is borne by owners of capital.

The Treasury Department and the Joint Committee on Taxation (JCT) have recently confirmed that the corporate income tax is a progressive tax. It is clear that the corporate tax is, in the short-term, borne by the (mostly wealthy) owners of capital — meaning it’s paid by the owners of corporate stocks and other business and investment assets because the tax reduces what corporations can pay out as dividends to their shareholders. The Treasury Department concluded that even in the long-run, 82 percent of the tax is borne by owners of capital.

This is an indication that the corporations’ offshore profits are held (officially, at least) in countries with no corporate income taxes — tax havens. Most of the countries that have consumer markets and developed economies where American companies can sell products also have corporate taxes. Most countries that do not have corporate income taxes are small countries like Bermuda and the Cayman Islands that provide little in the way of real business opportunities but are useful to multinational corporations as tax havens.

This is an indication that the corporations’ offshore profits are held (officially, at least) in countries with no corporate income taxes — tax havens. Most of the countries that have consumer markets and developed economies where American companies can sell products also have corporate taxes. Most countries that do not have corporate income taxes are small countries like Bermuda and the Cayman Islands that provide little in the way of real business opportunities but are useful to multinational corporations as tax havens.

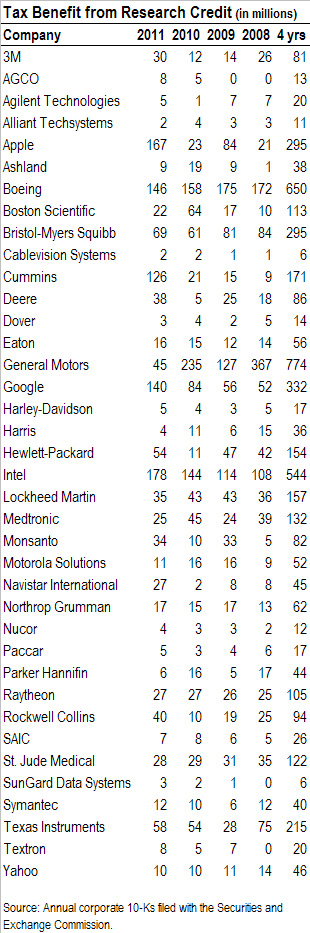

Congress should let the research credit expire, and redirect the billions of dollars that it costs into true, basic, truly scientific research, which businesses rarely engage in because the payoffs often take years to arrive.

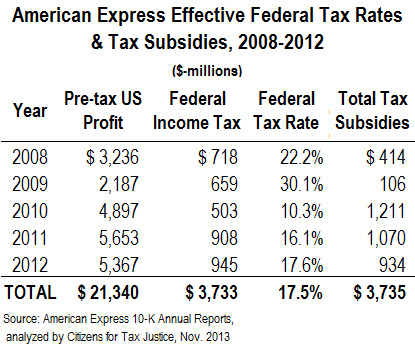

Congress should let the research credit expire, and redirect the billions of dollars that it costs into true, basic, truly scientific research, which businesses rarely engage in because the payoffs often take years to arrive. Even on the $21.3 billion in pretax profits that American Express officially earned in the U.S. over the past five years, the company has paid only half the 35 percent federal statutory tax rate. This means that over the past five years, American Express received over $3.7 billion in tax subsidies through the US tax code.

Even on the $21.3 billion in pretax profits that American Express officially earned in the U.S. over the past five years, the company has paid only half the 35 percent federal statutory tax rate. This means that over the past five years, American Express received over $3.7 billion in tax subsidies through the US tax code.

–Twitter has $107 million of unused stock option deductions—meaning that the next $107 million the company earns could be tax-free as a result of this single tax break. (Since the company has not yet reported a profitable year in the US, it’s impossible to estimate how long it will take the company to earn this amount going forward.)

–Twitter has $107 million of unused stock option deductions—meaning that the next $107 million the company earns could be tax-free as a result of this single tax break. (Since the company has not yet reported a profitable year in the US, it’s impossible to estimate how long it will take the company to earn this amount going forward.)