April 29, 2013 11:45 PM | Permalink | ![]()

Updated Figures Show 3.6% of U.S. Taxpayers would Face a Tax Increase

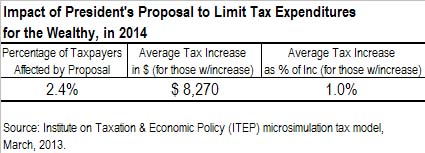

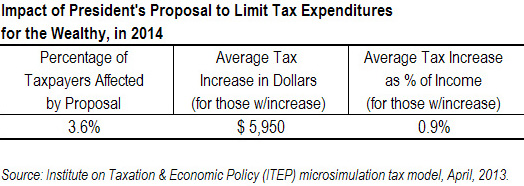

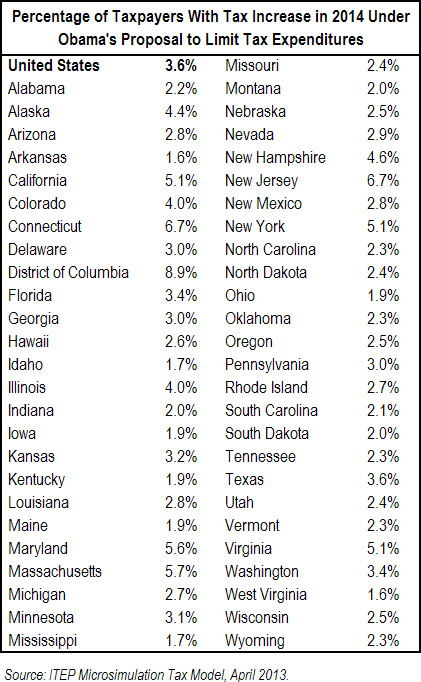

President Obama has proposed to limit the tax savings for high-income taxpayers from itemized deductions and certain other deductions and exclusions to 28 cents for each dollar deducted or excluded. This proposal would raise more than half a trillion dollars in revenue over the upcoming decade.[1] Despite this large revenue gain, only 3.6 percent of Americans would receive a tax increase under the plan in 2014, and their average tax increase would equal just less than one percent of their income.

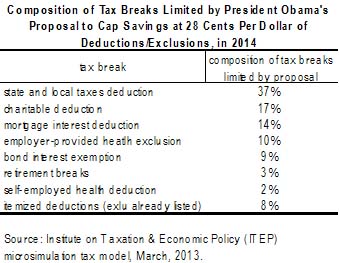

As illustrated in the table below, the deduction for state and local taxes would make up over a third of the total tax expenditures limited by the proposal. In combination, the deduction for state and local taxes and the deduction for charitable giving would make up just over half of the tax expenditures limited.

Previously published estimates from Citizens for Tax Justice of this proposal assumed that it would only affect taxpayers with adjusted gross income (AGI) above $250,000 for married couples and above $200,000 for singles.[2] Such an income threshold was included in the version of the proposal that appeared in the President’s jobs bill in 2011, the only actual legislative language for the proposal. However, documents recently released by the administration make clear that there is no longer such an income threshold. This change raises the share of U.S. taxpayers affected by the proposal by about one percentage point.

How the President’s “28 Percent Rule” Would Work

The President’s proposal is a way of limiting tax expenditures for the wealthy. The term “tax expenditures” refers to provisions that are considered to be government subsidies provided through the tax code. As such, these tax expenditures have the same effect as direct spending subsidies, because the Treasury ends up with less revenue and some individual or group receives money. But these tax subsidies are sometimes not recognized as spending programs because they are implemented through the tax code.

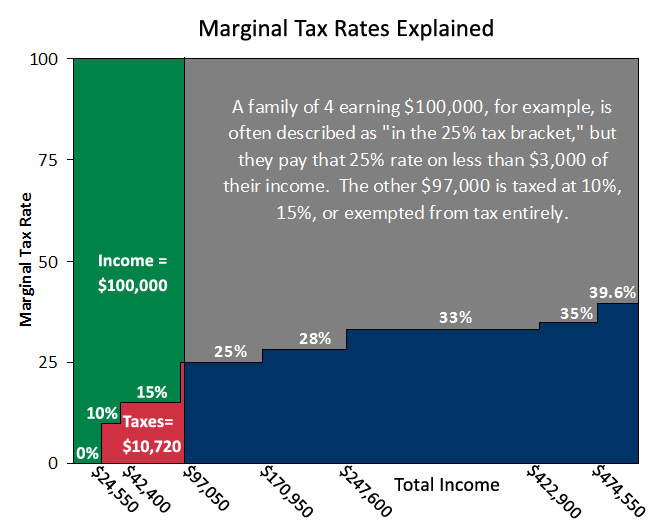

Under current law, there are three income tax brackets with rates higher than 28 percent (the 33, 35, and 39.6 percent brackets). People in these tax brackets (and people who would be in these tax brackets if not for their deductions and exclusions) could therefore lose some tax breaks under the proposal.[3]

Currently, a  high-income person in the 39.6 percent income tax bracket saves almost 40 cents for each dollar of deductions or exclusions. An individual in the 35 percent income tax bracket saves 35 cents for each dollar of deductions or exclusions, and a person in the 33 percent bracket saves 33 cents. The lower tax rates are 28 percent or less. Many middle-income people are in the 15 percent tax bracket and therefore save only 15 cents for each dollar of deductions or exclusions.

high-income person in the 39.6 percent income tax bracket saves almost 40 cents for each dollar of deductions or exclusions. An individual in the 35 percent income tax bracket saves 35 cents for each dollar of deductions or exclusions, and a person in the 33 percent bracket saves 33 cents. The lower tax rates are 28 percent or less. Many middle-income people are in the 15 percent tax bracket and therefore save only 15 cents for each dollar of deductions or exclusions.

This is an odd way to subsidize activities that Congress favors. If Congress provided such subsidies through direct spending, there would likely be a public outcry over the fact that rich people are subsidized at higher rates than low- and middle-income people. But because these subsidies are provided through the tax code, this fact has largely escaped the public’s attention.

President Obama initially presented his proposal to limit certain tax expenditures in his first budget plan in 2009, and included it in subsequent budget and deficit-reduction plans each year after that. The original proposal applied only to itemized deductions. The President later expanded the proposal to limit the value of certain “above-the-line” deductions (which can be claimed by taxpayers who do not itemize), such as the deduction for health insurance for the self-employed and the deduction for contributions to individual retirement accounts (IRA). [4]

Most recently, the proposal was also expanded to include certain tax exclusions, such as the exclusion for interest on state and local bonds and the exclusion for employer-provided health care. Exclusions provide the same sort of benefit as deductions, the only difference being that they are not counted as part of a taxpayer’s income in the first place (and therefore do not need to be deducted).

Exempting the Charitable Deduction from the 28% Limit

Would Reduce the Revenue Gain by 19 Percent

Any proposal to limit tax expenditures gives rise to a debate about which tax expenditures should be subject to such a limit and which should be exempt. For example, some charities have objected to the limit applying to the deduction for charitable giving, on the mistaken view that limiting this deduction would significantly reduce charitable giving.[5]

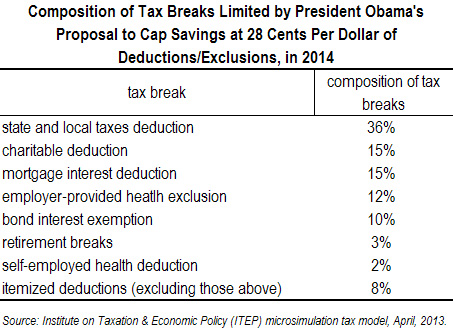

Excluding a tax expenditure from the proposed limit may reduce the revenue impact of the proposal slightly more than or less than the corresponding percentage in the table on the second page. For example, while the table on the second page illustrates that the charitable deduction makes up 15 percent of the tax breaks that would be limited under the President’s proposal, exempting the charitable deduction from the limit would actually reduce the revenue impact by 19 percent. While the table on the second page illustrates that the deduction for state and local taxes makes up 36 percent of the total tax breaks limited by the proposal, exempting this deduction from the limit would reduce the revenue impact of the proposal by 34 percent. The reason for these slight differences reflects interactions among various tax provisions.

Exempting the Charitable Deduction from the Proposed Limit would Largely Turn the

Remaining Proposal into a Limit on the Value of Deductions for State and Local Taxes

Some tax-exempt organizations, particularly universities and museums, have expressed fear that the limitation on the value of the charitable deduction will result in less charitable giving. Research suggests this fear is unfounded.[6] But another point that has received little attention is that amending the President’s proposal to “carve out” the charitable deduction would concentrate the effects of the proposal even more on the deduction for state and local taxes — which is the most justifiable of all the tax breaks the President proposes to limit.

The deduction for state and local taxes paid is sometimes seen as a subsidy for state and local governments because it effectively transfers the cost of some state and local taxes away from the residents who directly pay them and onto the federal government. For example, if a state imposes a higher income tax rate on residents who are in the 39.6 percent federal income tax bracket, that means that each dollar of additional state income taxes could reduce federal income taxes on these high-income residents by almost 40 cents. The state government may thus be more willing to enact the tax increase because its high-income residents will really only pay 60 percent of the tax increase, while the federal government will effectively pay the remaining 39.6 percent.

But viewed a different way, the deduction for state and local taxes is not a tax expenditure at all, but instead is a way to define the amount of income a taxpayer has available to pay federal income taxes. State and local taxes are an expense that reduces one’s ability to pay federal income taxes in a way that is generally out of the control of the taxpayer. A taxpayer in a high-tax state has less income to pay federal income taxes than a taxpayer with the same pre-tax income but residing in a low-tax state.

Another argument in favor of the itemized deduction for state and local taxes paid is that the public investments funded by state and local taxes produce benefits for the entire nation. This can be seen as a justification for the deduction for state and local taxes paid because it encourages state and local governments to raise the tax revenue to fund these public investments that the jurisdictions might otherwise not make.

For example, state and local governments provide roads that, in addition to serving local residents, facilitate interstate commerce. State and local governments also provide education to those who may leave the jurisdiction and boost the skill level of the nation as a whole, boosting the productivity of the national economy. State and local governments may have an incentive to provide less of these public investments than is optimal for the nation because the benefits partly go to those outside the jurisdiction. The deduction for state and local taxes may counter this inclination of state and local governments to under-invest in these areas.

[1] Citizens for Tax Justice, “President Obama’s Tax Proposals in his Fiscal 2014 Budget Plan,” April 11, 2013. http://ctj.org/ctjreports/2013/04/president_obamas_tax_proposals_in_his_fiscal_2014_budget_plan.php

[2] This report replaces the report with those previous estimates, titled “Who Loses Which Tax Breaks Under President Obama’s Proposed Limit on Tax Expenditures?” which was published on March 29, 2013.

[3] Many of the wealthy taxpayers whose deductions and exclusions are targeted by the proposal would also experience a change in their alternative minimum tax (AMT). The AMT is a backstop tax, meaning it forces well-off people who effectively reduce their taxable income with various deductions and exclusions to pay some minimal tax. If a tax change only increases the regular income tax and not the AMT, some taxpayers who currently pay AMT will not be affected at all. Very generally, one of the AMT changes in the proposal essentially ensures that the increase in a taxpayer’s regular income tax would also be applied to the AMT to ensure that the tax increase shows up on the final income tax bill. The other AMT change would limit the savings for each dollar of deductions or exclusions to 28 cents for those whose income is within the “phase-out range” for the exemption that prevents most people from being affected by the AMT. The impacts of these changes are included in the estimates shown here.

[4] The most recent description of the proposal provided by the Obama administration can be found in Department of the Treasury, “General Explanations of the Administration’s Fiscal Year 2014 Revenue Proposals,” April 2013, page 134. http://www.treasury.gov/resource-center/tax-policy/Documents/General-Explanations-FY2014.pdf

[5] For example, see Joseph Cordes, “Effects of Limiting Charitable Deductions on Nonprofit Finances,” presentation given February 28, 2013 at the Urban Institute. Cordes finds that the President’s proposal to limit the tax savings of each dollars of deductions and exclusions to just 28 cents would reduce charitable giving by individuals by between 2.2 percent and 4.1 percent, and the actual loss of total charitable giving would be smaller because some charitable contributions are made by foundations, corporations and other entities rather than individuals affected by this proposal. http://www.urban.org/taxandcharities/upload/cordesv5.pdf

[6] Id.

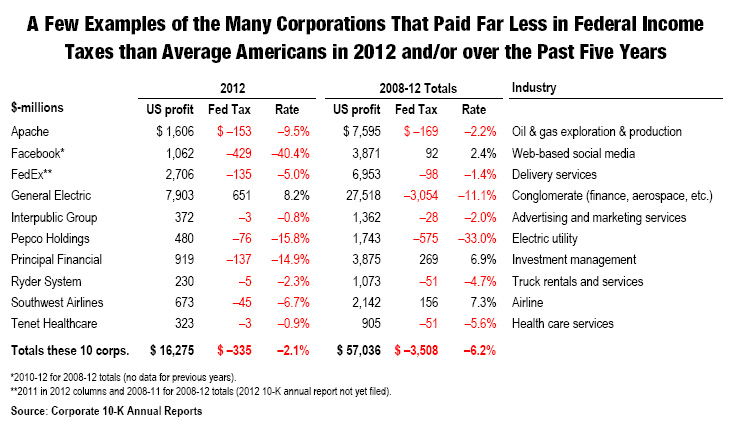

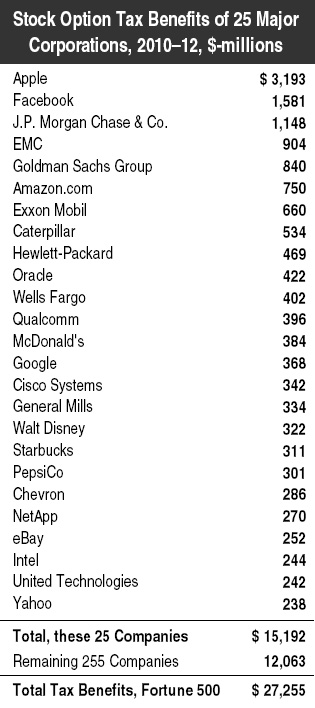

Earlier this year, Citizens for Tax Justice reported that Facebook Inc. had used a single tax break, for executive stock options, to avoid paying even a dime of federal and state income taxes in 2012. Since then, CTJ has investigated the extent to which other large companies are using the same tax break. This short report presents data for 280 Fortune 500 corporations that, like Facebook, disclose a portion of the tax benefits they receive from this tax break.

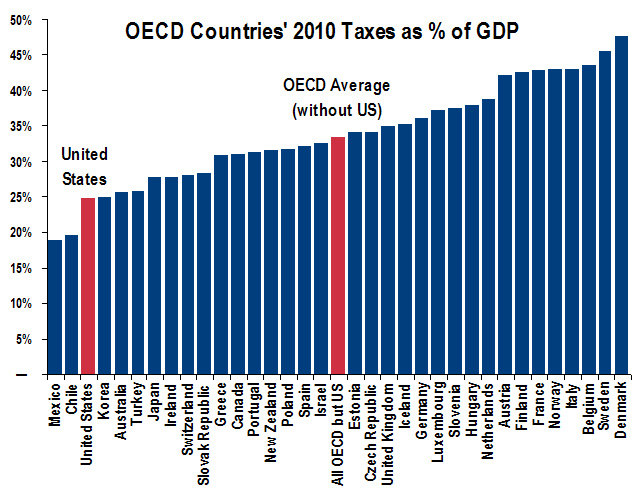

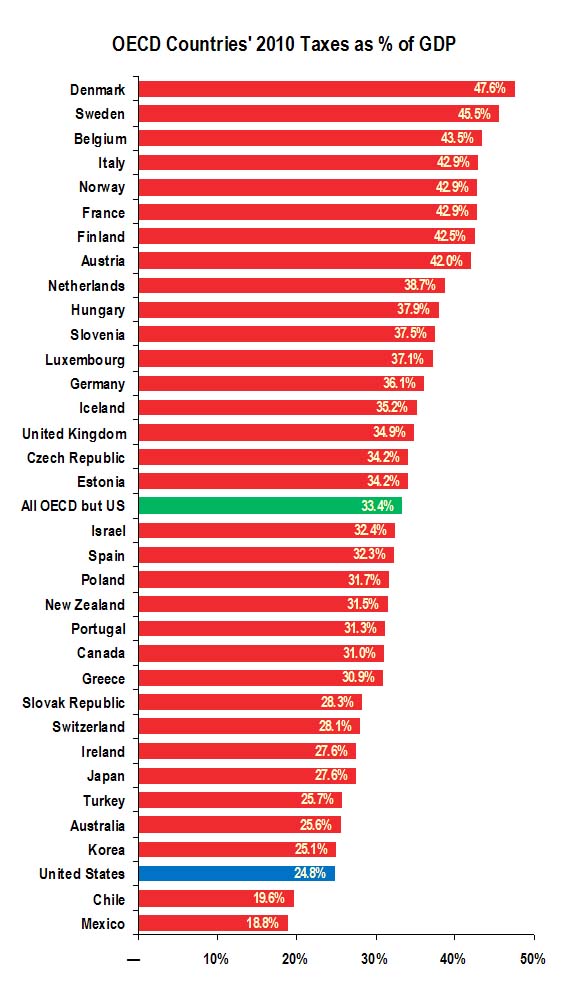

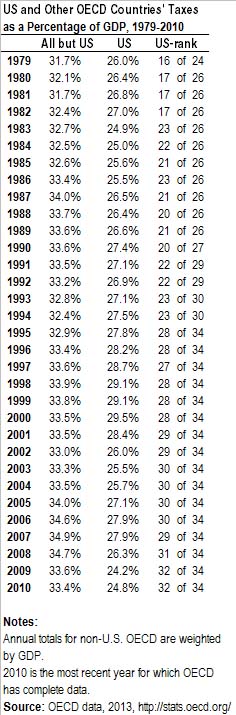

Earlier this year, Citizens for Tax Justice reported that Facebook Inc. had used a single tax break, for executive stock options, to avoid paying even a dime of federal and state income taxes in 2012. Since then, CTJ has investigated the extent to which other large companies are using the same tax break. This short report presents data for 280 Fortune 500 corporations that, like Facebook, disclose a portion of the tax benefits they receive from this tax break. Senator Bernie Sanders of Vermont recently appeared on Real Time with Bill Maher and disputed the claim by the Tax Foundation that the U.S. has the highest corporate tax in the world.

Senator Bernie Sanders of Vermont recently appeared on Real Time with Bill Maher and disputed the claim by the Tax Foundation that the U.S. has the highest corporate tax in the world.