April 1, 2015 01:23 PM | Permalink |

Hundreds More Likely Do the Same, Avoiding $600 Billion in U.S. Taxes

Read this report in PDF (Includes Company by Company Appendices)

Download the Company by Company PRE Data (XLS)

It’s been well documented that major U.S. multinational corporations are stockpiling profits offshore to avoid U.S. taxes. Congressional hearings over the past few years have raised awareness of tax avoidance strategies of major technology corporations such as Apple and Microsoft, but, as this report shows, a diverse array of companies are using offshore tax havens, including the pharmaceutical giant Amgen, the apparel manufacturer Nike, the supermarket chain Safeway, the financial firm American Express, banking giants Bank of America and Wells Fargo, and even more obscure companies such as Advanced Micro Devices and Group 1 Automotive.

It’s been well documented that major U.S. multinational corporations are stockpiling profits offshore to avoid U.S. taxes. Congressional hearings over the past few years have raised awareness of tax avoidance strategies of major technology corporations such as Apple and Microsoft, but, as this report shows, a diverse array of companies are using offshore tax havens, including the pharmaceutical giant Amgen, the apparel manufacturer Nike, the supermarket chain Safeway, the financial firm American Express, banking giants Bank of America and Wells Fargo, and even more obscure companies such as Advanced Micro Devices and Group 1 Automotive.

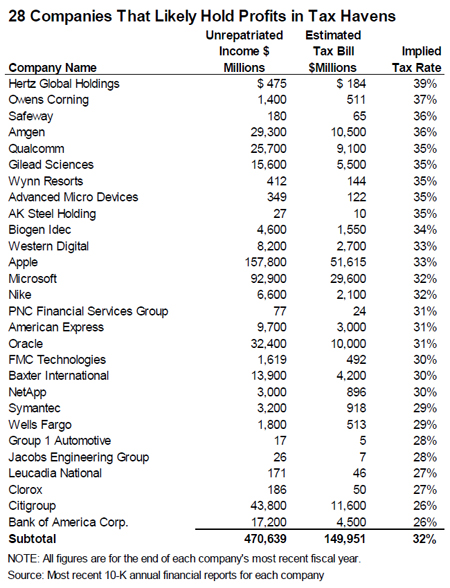

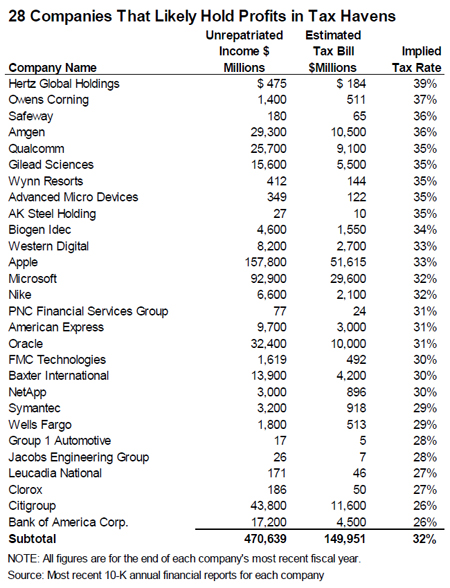

All told, American Fortune 500 corporations are avoiding up to $600 billion in U.S. federal income taxes by holding more than $2.1 trillion of “permanently reinvested” profits offshore. In their latest annual financial reports, twenty-eight of these corporations reveal that they have paid an income tax rate of 10 percent or less in countries where these profits are officially held, indicating that most of these profits are likely in offshore tax havens.

How We Know When Multinationals’ Offshore Cash is Largely in Tax Havens

Offshore profits that an American corporation “repatriates” (officially brings back to the United States) are subject to the U.S. tax rate of 35 percent minus a tax credit equal to whatever taxes the company paid to foreign governments. Thus, if an American corporation reports it would pay a U.S. tax rate of 25 percent or more on its offshore profits, that indicates it has paid foreign governments a tax rate of 10 percent or less.

Twenty-eight American corporations have acknowledged paying less than a 10 percent foreign tax rate on the $470 billion they collectively hold offshore. The table on the following page shows the disclosures made by these 28 corporations in their most recent annual financial reports.

It is almost always the case that profits reported by American corporations to the IRS as earned in tax havens were actually earned in the United States or another country with a tax system similar to ours. Most economically developed countries (places where there are real business opportunities for American corporations) have a corporate income tax rate of at least 20 percent, and typically tax rates are higher.

Countries that have no corporate income tax or a very low corporate tax — countries such as Bermuda, the Cayman Islands, and the Bahamas — provide very little in the way of real business opportunities for American corporations like Qualcomm, Safeway, and Microsoft. But large Americans corporations use accounting gimmicks (most of which are, unfortunately, allowed under current law) to make profits appear to be earned in tax haven countries. In fact, a 2014 CTJ examination of corporate financial filings found U.S. corporations collectively report earning profits in Bermuda and the Cayman Islands that are 16 times the gross domestic products of each of those countries, which is clearly impossible.

Hundreds of Other Fortune 500 Corporations Don’t Disclose Tax Rates They’d Pay if They Repatriated Their Profits

At the end of 2014, 304 Fortune 500 companies collectively held a whopping $2.15 trillion offshore. (A full list of these 304 corporations is published as an appendix to this paper.)

Clearly, the 28 companies that report the U.S. tax rate they would pay if they repatriated their profits are not alone in shifting their profits to low-tax havens—they’re only alone in disclosing it. The vast majority of these companies — 247 out of 304 —decline to disclose the U.S. tax rate they would pay if these offshore profits were repatriated. (57 corporations, including the 28 companies shown on this page, disclose this information. A full list of the 57 companies is published as an appendix to this paper.) The non-disclosing companies collectively hold $1.56 trillion in unrepatriated offshore profits at the end of 2014.

Accounting standards require publicly held companies to disclose the U.S. tax they would pay upon repatriation of their offshore profits — but these standards also provide a gaping loophole allowing companies to assert that calculating this tax liability is “not practicable.” Almost all of the 247 non-disclosing companies use this loophole to avoid disclosing their likely tax rates upon repatriation — even though these companies almost certainly have the capacity to estimate these liabilities.

Hundreds of Billions in Tax Revenue at Stake

It’s impossible to know precisely how much income tax would be paid, under current tax rates, upon repatriation by the 247 Fortune 500 companies that have disclosed holding profits overseas but have failed to disclose how much U.S. tax would be due if the profits were repatriated. But if these companies paid the same 29 percent average tax rate as the 57 disclosing companies, the resulting one-time tax would total $432 billion for these 247 companies. Added to the $169 billion tax bill estimated by the 57 companies who did disclose, this means that taxing all “permanently reinvested” foreign income of the 304 companies at the current federal tax rate could result in $601 billion in added corporate tax revenue.

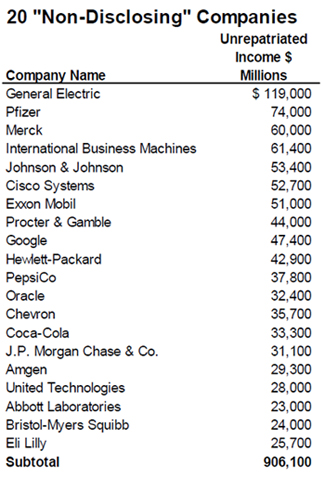

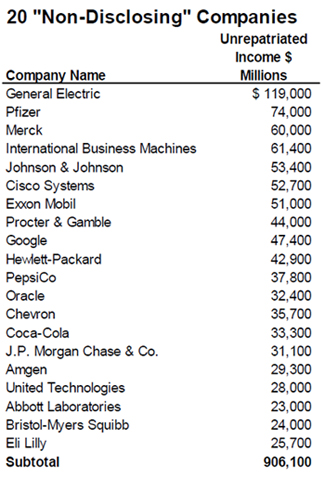

20 of the Biggest “Non-Disclosing” Companies Hold $906 Billion Offshore

While hundreds of companies refuse to disclose the tax they likely owe on their offshore cash, just a handful of these companies account for the lion’s share of the permanently reinvested foreign profits in the Fortune 500. The nearby table shows the 20 non-disclosing companies with the biggest offshore stash at the end of the most recent fiscal year. These 20 companies held $906 billion in unrepatriated offshore income — more than half of the total income held by the 247 “non-disclosing” companies. Most of these companies also disclose, elsewhere in their financial reports, owning subsidiaries in known tax havens. For example:

While hundreds of companies refuse to disclose the tax they likely owe on their offshore cash, just a handful of these companies account for the lion’s share of the permanently reinvested foreign profits in the Fortune 500. The nearby table shows the 20 non-disclosing companies with the biggest offshore stash at the end of the most recent fiscal year. These 20 companies held $906 billion in unrepatriated offshore income — more than half of the total income held by the 247 “non-disclosing” companies. Most of these companies also disclose, elsewhere in their financial reports, owning subsidiaries in known tax havens. For example:

■ General Electric disclosed holding $119 billion offshore at the end of 2014. GE has subsidiaries in the Bahamas, Bermuda, Ireland and Singapore, but won’t disclose how much of its offshore cash is in these low-tax destinations. [Some of it is clearly there; see text box below.]

■ Pfizer has subsidiaries in the Cayman Islands, Ireland, the Isle of Jersey, Luxembourg and Singapore, but does not disclose how much of its $74 billion in offshore profits are stashed in these tax havens.

■ Merck has10 subsidiaries in Bermuda alone. It’s unclear how much of its $60 billion in offshore profits are being stored (for tax purposes) in this tiny island.

Congress Should Act

While corporations’ offshore holdings have grown gradually over the past decade, there are two reasons it is vital that Congress act promptly to deal with this problem. First, a large number of the biggest corporations appear to be increasing their offshore cash significantly. Seventy-seven of the companies surveyed in this report increased their declared offshore cash by at least $500 million each in the last year alone. Seven particularly aggressive companies each increased their permanently reinvested foreign earnings by more than $5 billion in the past year. These include Apple, General Electric, Microsoft, IBM, Google, Oracle and Gilead Sciences.

A second reason for concern is that companies are aggressively seeking to permanently shelter their offshore cash from U.S. taxation by engaging in corporate inversions, through which companies acquire smaller foreign companies and reincorporate in foreign countries, thus avoiding most or all U.S. tax on their profits.

|

Even “Non-Disclosers” Slip Up Sometimes

As noted above, General Electric does not disclose the U.S. tax it would owe if its $110 billion offshore stash was repatriated. But in its 2009 annual report, GE noted that it had reclassified $2 billion of previously earned foreign profits as “permanently reinvested” offshore, and said that this change resulted “in an income tax benefit of $700 million.” Since $700 million is 35 percent of $2 billion, this is an admission that the expected foreign tax rate on this $2 billion of offshore cash was exactly zero, which in turn strongly suggests that GE’s “permanent reinvestment” plan for this $2 billion involved assigning it to one of its tax haven subsidiaries.

|

What Should Be Done?

Many large multinationals that fail to disclose whether their offshore profits are officially in tax havens are the same companies that have lobbied heavily for tax breaks on their offshore cash. These companies propose the government either enact a temporary “tax holiday” for repatriation, which would allow companies to officially bring offshore profits back to the U.S. and pay a very low tax rate on the repatriated income, or give them a permanent exemption for offshore income in the form of a “territorial” tax system. Either of these proposals would increase the incentive for multinationals to shift their U.S. profits, on paper, into tax havens.

A far more sensible solution would be to simply end “deferral,” that is, repealing the rule that indefinitely exempts offshore profits from U.S. income tax until these profits are repatriated. Ending deferral would mean that all profits of U.S. corporations, whether they are generated in the U.S. or abroad, would be taxed by the United States in the year they are earned. Of course, American corporations would continue to receive a “foreign tax credit” against any taxes they pay to foreign governments, to ensure profits are not double-taxed.

Conclusion

The limited disclosures made by a handful of Fortune 500 corporations show that corporations are brazenly using tax havens to avoid taxes on significant profits. But the scope of this tax avoidance is likely much larger, since the vast majority of Fortune 500 companies with offshore cash refuse to disclose how much tax they would pay on repatriating their offshore profits.

Lawmakers should resist calls for tax changes, such as repatriation holidays or a territorial tax system, that would reward U.S. companies for shifting their profits to tax havens. If the Securities and Exchange Commission required more complete disclosure about multinationals’ offshore profits, it would become obvious that Congress should end deferral, thereby eliminating the incentive for multinationals to shift their profits offshore once and for all.

For the full list of unrepatriated profits and taxes owed, click to read the pdf or download the Excel spreadsheet.

![]()

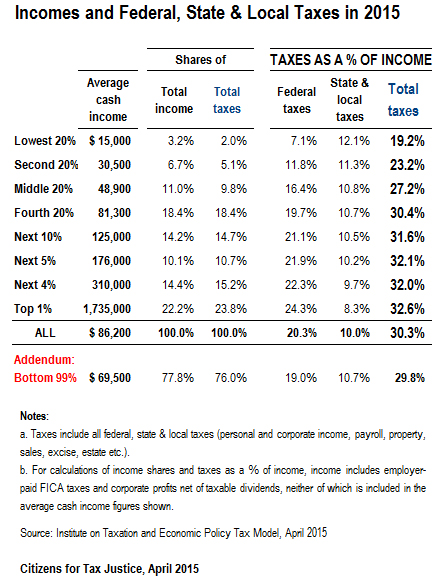

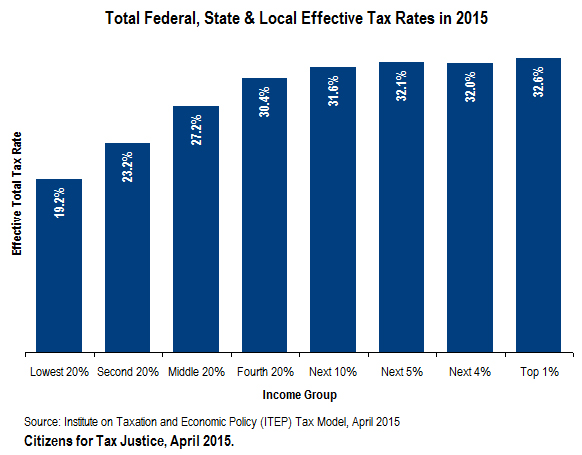

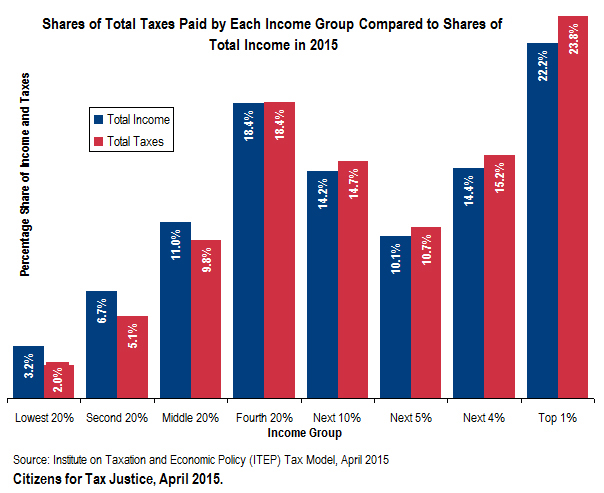

But in sum, the nation’s tax system is barely progressive. Those who advocate for top-heavy tax cuts and erroneously claim the wealthy are overtaxed focus solely on the federal personal income tax, while ignoring other taxes that Americans pay. As the table to the right illustrates, the total share of taxes (federal, state, and local) that will be paid by Americans across the economic spectrum in 2015 is roughly equal to their total share of income.

But in sum, the nation’s tax system is barely progressive. Those who advocate for top-heavy tax cuts and erroneously claim the wealthy are overtaxed focus solely on the federal personal income tax, while ignoring other taxes that Americans pay. As the table to the right illustrates, the total share of taxes (federal, state, and local) that will be paid by Americans across the economic spectrum in 2015 is roughly equal to their total share of income.

It’s been well documented that major U.S. multinational corporations are stockpiling profits offshore to avoid U.S. taxes. Congressional hearings over the past few years have raised awareness of tax avoidance strategies of major technology corporations such as Apple and Microsoft, but, as this report shows, a diverse array of companies are using offshore tax havens, including the pharmaceutical giant Amgen, the apparel manufacturer Nike, the supermarket chain Safeway, the financial firm American Express, banking giants Bank of America and Wells Fargo, and even more obscure companies such as Advanced Micro Devices and Group 1 Automotive.

It’s been well documented that major U.S. multinational corporations are stockpiling profits offshore to avoid U.S. taxes. Congressional hearings over the past few years have raised awareness of tax avoidance strategies of major technology corporations such as Apple and Microsoft, but, as this report shows, a diverse array of companies are using offshore tax havens, including the pharmaceutical giant Amgen, the apparel manufacturer Nike, the supermarket chain Safeway, the financial firm American Express, banking giants Bank of America and Wells Fargo, and even more obscure companies such as Advanced Micro Devices and Group 1 Automotive. While hundreds of companies refuse to disclose the tax they likely owe on their offshore cash, just a handful of these companies account for the lion’s share of the permanently reinvested foreign profits in the Fortune 500. The nearby table shows the 20 non-disclosing companies with the biggest offshore stash at the end of the most recent fiscal year. These 20 companies held $906 billion in unrepatriated offshore income — more than half of the total income held by the 247 “non-disclosing” companies. Most of these companies also disclose, elsewhere in their financial reports, owning subsidiaries in known tax havens. For example:

While hundreds of companies refuse to disclose the tax they likely owe on their offshore cash, just a handful of these companies account for the lion’s share of the permanently reinvested foreign profits in the Fortune 500. The nearby table shows the 20 non-disclosing companies with the biggest offshore stash at the end of the most recent fiscal year. These 20 companies held $906 billion in unrepatriated offshore income — more than half of the total income held by the 247 “non-disclosing” companies. Most of these companies also disclose, elsewhere in their financial reports, owning subsidiaries in known tax havens. For example:

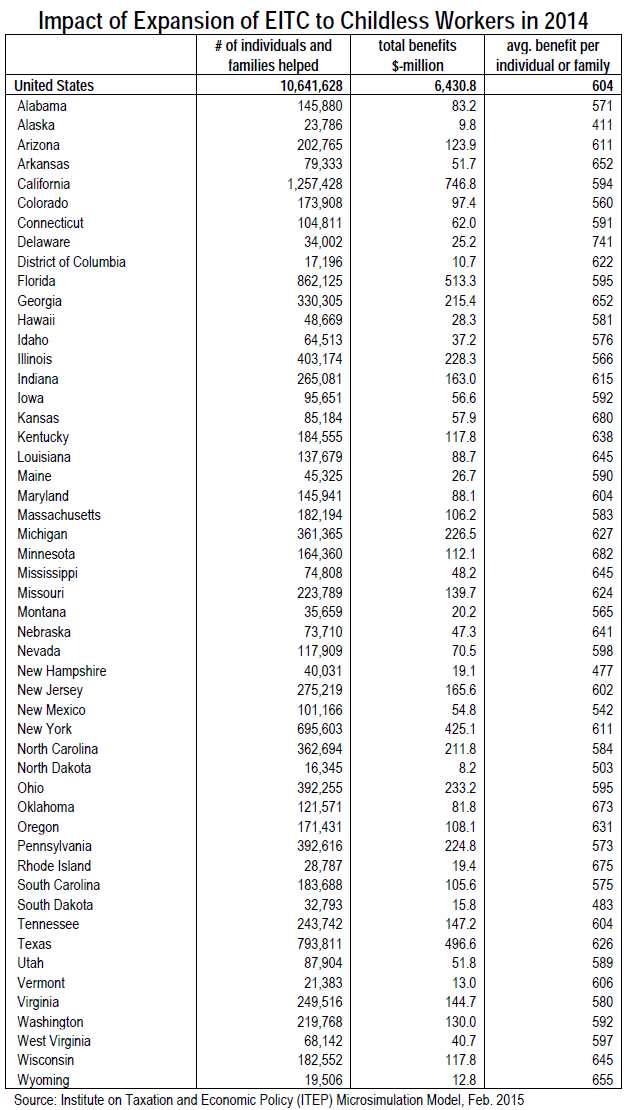

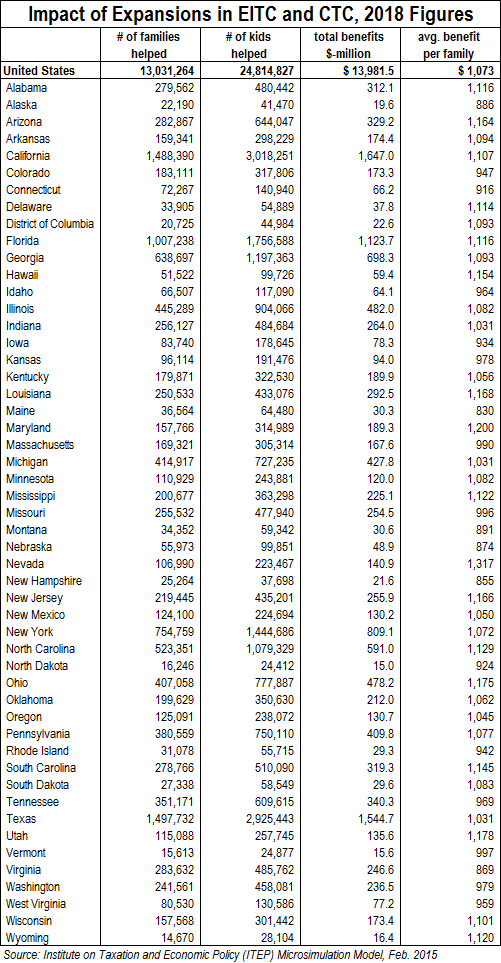

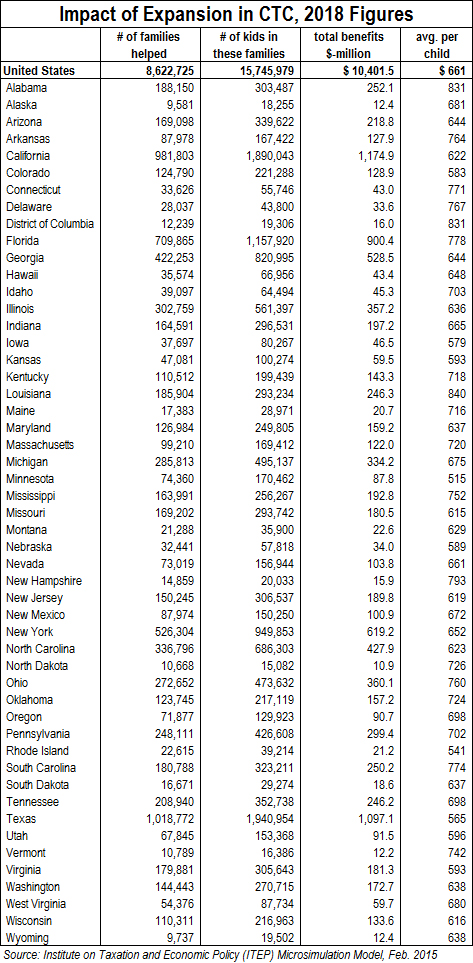

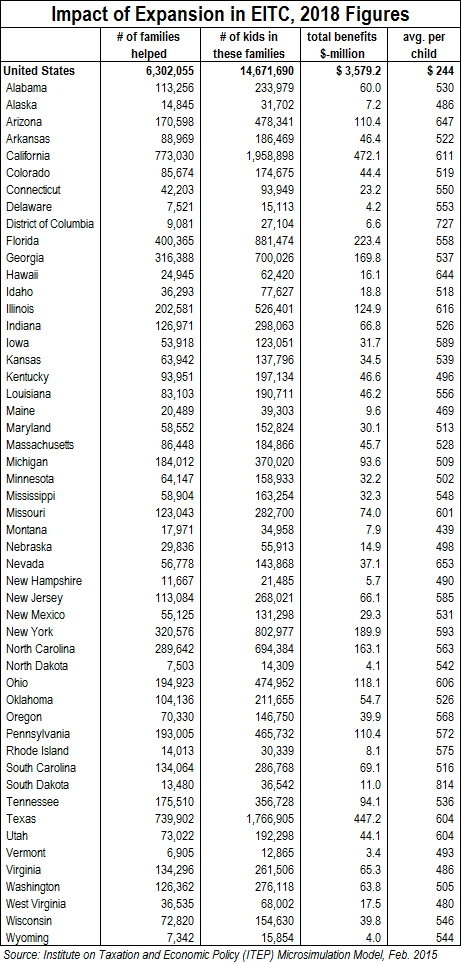

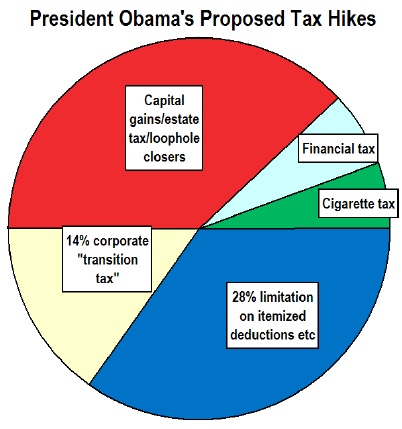

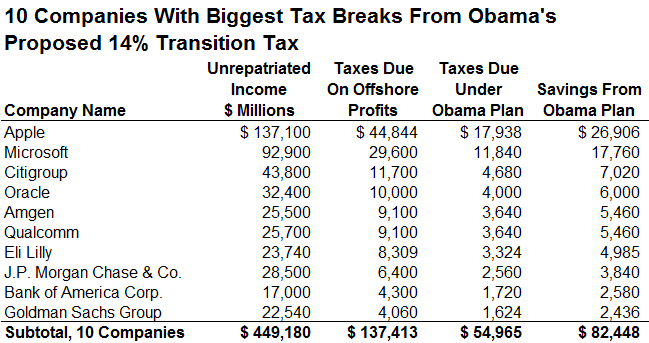

President Obama’s budget would raise about $1.7 trillion in new tax revenues over the next ten years.

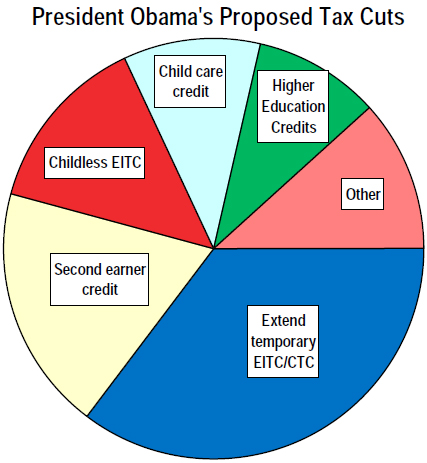

President Obama’s budget would raise about $1.7 trillion in new tax revenues over the next ten years. The president’s budget would use about a third of the revenues from his proposed tax increases to cut taxes. Almost all of these tax cuts are designed to benefit middle- and low-income working families.

The president’s budget would use about a third of the revenues from his proposed tax increases to cut taxes. Almost all of these tax cuts are designed to benefit middle- and low-income working families.

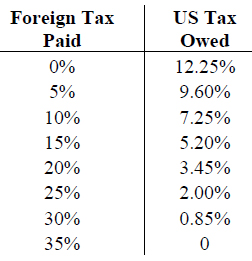

Delaney’s fallback proposal would end the deferral of U.S. taxes on offshore profits of American companies, but it would exempt a significant percentage of “active income” depending on the taxes, if any, already paid to foreign countries. For example, a companywith all of its offshore money in tax havens (with no tax paid) would pay the U.S. government only a 12.25 percent tax rate on its “active” foreign income. A company that paid a 25 percent rate on offshore income would owe the U.S. only 2 percent in taxes on “active” income. (See the table for a breakdown of the rate paid at different levels of foreign taxes.) For “passive” income, however, Delaney follows Baucus’s Option Z, and would not allow any exemption from the 35 percent U.S. corporate tax rate. “Passive income” includes income such as royalties that are very easy to shift into tax havens.

Delaney’s fallback proposal would end the deferral of U.S. taxes on offshore profits of American companies, but it would exempt a significant percentage of “active income” depending on the taxes, if any, already paid to foreign countries. For example, a companywith all of its offshore money in tax havens (with no tax paid) would pay the U.S. government only a 12.25 percent tax rate on its “active” foreign income. A company that paid a 25 percent rate on offshore income would owe the U.S. only 2 percent in taxes on “active” income. (See the table for a breakdown of the rate paid at different levels of foreign taxes.) For “passive” income, however, Delaney follows Baucus’s Option Z, and would not allow any exemption from the 35 percent U.S. corporate tax rate. “Passive income” includes income such as royalties that are very easy to shift into tax havens.