December 4, 2014 04:03 PM | Permalink |

PDF of this report.

After President Barack Obama’s veto threat last week ended discussion of a $450 billion package of tax breaks mostly benefiting businesses, the House of Representatives approved a smaller bill, H.R. 5771, that would extend most of the tax cuts for one year at a cost of $42 billion. While the President deserves credit for stopping a much bigger corporate giveaway, even the $42 billion bill is an absurd waste of money from a Congress that has been unable to find a way to fund basic public investments like highways and bridges.

Here are just a few of the problems with H.R. 5771:

■ Most of the tax breaks fail to achieve any desirable policy goals. For example, they include bonus depreciation breaks for investments in equipment that the Congressional Research Service have found to be a “relatively ineffective tool for stimulating the economy,[1] a tax credit for research defined so loosely that it includes the work soft drink companies put into developing new flavors,[2] and a tax break that allows General Electric to do financial business offshore without paying U.S. taxes on the profits.

■ The tax breaks cannot possibly be effective in encouraging businesses to do anything because they are almost entirely retroactive. The tax breaks actually expired at the end of 2013 and this bill will extend them (almost entirely retroactively) through 2014. These tax provisions are supposedly justified as incentives for companies to do things Congress thinks are desirable, like investing in equipment or research, but that justification makes no sense when tax breaks are provided to businesses for things they have done in the past.

■ The bill increases the deficit by $42 billion to provide tax breaks that mostly benefit businesses, even after members of Congress have refused to enact any measure that helps working people unless the costs are offset. The measures that Congress refused to enact without offsets include everything from creating jobs by funding highway projects[3] to extending emergency unemployment benefits.[4]

It’s Smaller than the Previous Proposal — But Still a Wasteful Corporate Giveaway

If approved by the Senate and signed by the President, the bill will cap a long debate over the fate of the tax extenders, the provisions that Congress has often enacted every couple of years to extend a long list of temporary tax breaks that mostly benefit businesses. While the Senate seemed ready this year to enact an $85 billion bill to extend these breaks for two years, the House of Representatives took a different approach and approved several bills that would make some of these tax breaks permanent, increasing the budget deficit by hundreds of billions of dollars.

An attempt by lawmakers from both parties to combine these approaches — making some breaks permanent while extending the rest for two years at a total cost of $450 billion — was torpedoed by the President’s veto threat last week.[5] In response, the House Republican leadership brought to the floor the new bill to extend most of the breaks for just one year, at a cost of $42 billion.

The cost of the tax extenders will be far greater if Congress does not break its habit of extending these provisions over and over. In that scenario, the Congressional Budget Office estimates that these tax breaks will cost about $700 billion over the coming decade.[6]

Details on the Most Costly Tax Extenders

Often a lawmaker or a special interest group will argue that the tax extender legislation should be enacted because it includes some provision that seems well-intentioned but makes up only a tiny fraction of the cost of the overall package of tax breaks.

For example, some support the deduction for teachers who purchase classroom supplies out of their own pockets. Never mind that this provides a tiny benefit that hardly excuses the absurdity that teachers are forced to purchase school supplies with their own money. (A school teacher in the 15 percent income tax bracket saves less than $40 a year under this provision). The important point is that this break makes up just 0.5 percent of the cost of the tax extenders package. It cannot possibly justify enacting the entire package of tax breaks.

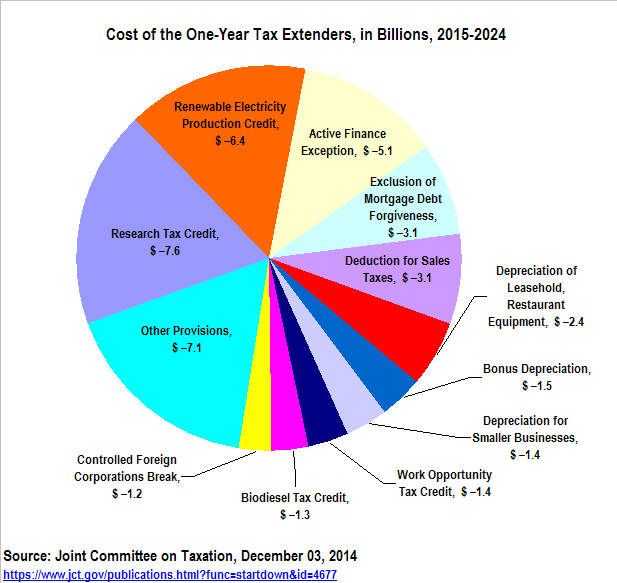

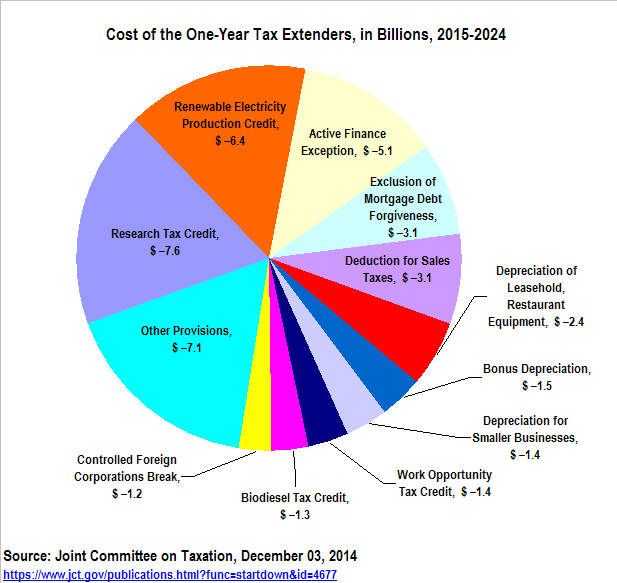

Here are some of the most costly tax provisions extended by this bill.

Bonus Depreciation

Bonus depreciation could be far more costly than it appears. The official revenue estimate provided by Congress’s Joint Committee on Taxation (JCT) shows that this tax break will reduce revenue by $1.5 billion. However, if Congress continues to extend these tax breaks throughout the coming decade — a very real possibility given Congress’s history in recent years — bonus depreciation will reduce revenue by $244 billion over that period, accounting for 35 percent of the cost of tax extenders and the most expensive provision in the package. This is explained in the box on the following page.

Bonus depreciation is a significant expansion of existing breaks for business investment. Unfortunately, Congress does not seem to understand that business people make decisions about investing and expanding their operations based on whether or not there are customers who want to buy whatever product or service they provide. A tax break subsidizing investment will benefit those businesses that would have invested anyway but is unlikely to result in much, if any, new investment.

Companies are allowed to deduct from their taxable income the expenses of running the business, so that what’s taxed is net profit. Businesses can also deduct the costs of purchases of machinery, software, buildings and so forth, but since these capital investments don’t lose value right away, these deductions are taken over time. In other words, capital expenses (expenditures to acquire assets that generate income over a long period of time) usually must be deducted over a number of years to reflect their ongoing usefulness.

In most cases firms would rather deduct capital expenses right away rather than delaying those deductions, because of the time value of money, i.e., the fact that a given amount of money is worth more today than the same amount of money will be worth if it is received later. For example, $100 invested now at a 7 percent return will grow to $200 in ten years.

Bonus depreciation is a temporary expansion of the existing breaks that allow businesses to deduct these costs more quickly than is warranted by the equipment’s loss of value or any other economic rationale.

A report from the Congressional Research Service reviews efforts to quantify the impact of bonus depreciation and explains that “the studies concluded that accelerated depreciation in general is a relatively ineffective tool for stimulating the economy.”[7]

|

Bonus Depreciation Is Actually the Most Expensive Tax Extender

The pie graph above, based on cost estimates for the provisions in H.R. 5771 provided by Congress’s Joint Committee on Taxation (JCT), puts the cost of a one-year extension of bonus depreciation at about $1.5 billion. But if Congress continues to extend these provisions instead of allowing them to expire, bonus depreciation will cost $244 over the coming decade, according to the Congressional Budget Office, making it the most expensive tax extender.

Anyone examining JCT’s estimates of the cost of bonus depreciation would find something that seems strange. The provision reduces revenue by over $45 billion in 2015 and then seems to raise some money each year after, resulting in the relatively small net cost of $1.5 billion at the end of the decade. That’s because bonus depreciation allows companies to take deductions for the cost of equipment more quickly than they otherwise would. Because those deductions will then be unavailable in later years when they would have otherwise been claimed, the Treasury will actually collect more revenue during the rest of the decade.

But if Congress keeps extending bonus depreciation through the coming decade — which seems like a real possibility — that would mean deductions are moved forward every year and the Treasury would never recoup most of those costs. The cost of bonus depreciation would balloon, making up 35 percent of the costs of the tax extenders over the coming decade.

|

Research Tax Credit

A report from Citizens for Tax Justice explains that the research credit needs to be reformed dramatically or allowed to expire.[8] One aspect of the credit that needs to be reformed is the definition of research. As it stands now, accounting firms are helping companies obtain the credit to subsidize redesigning food packaging and other activities that most Americans would see no reason to subsidize. The uncertainty about what qualifies as eligible research also results in substantial litigation and seems to encourage companies to push the boundaries of the law and often cross them.

Another aspect of the credit that needs to be reformed is the rules governing how and when firms obtain the credit. For example, Congress should bar taxpayers from claiming the credit on amended returns, because the credit cannot possibly be said to encourage research if the claimant did not even know about the credit until after the research was conducted.

As it stands now, some major accounting firms approach businesses and tell them that they can identify activities the companies carried out in the past that qualify for the research credit, and then help the companies claim the credit on amended tax returns. When used this way, the credit obviously does not accomplish the goal of increasing the amount of research conducted by businesses.

Renewable Electricity Production Tax Credit

The renewable electricity production tax credit (PTC) subsidizes the generation of electricity from wind and other renewable sources. The credit is 2.3 cents per kilowatt for electricity generated from wind turbines and less for energy produced by other types of renewable sources.

First created in 1992, the PTC has been criticized by many conservative lawmakers and organizations that tend to not object to other tax extenders, perhaps because they see wind energy as a competitor to fossil fuels.[9]

Unlike most other tax extenders, the PTC was last extended for only one year. However, the cost estimate for the PTC was larger than usual at that time because that law also expanded the PTC by allowing wind turbines (and other such facilities) to qualify so long as their construction began during 2013, whereas before the turbines had to be up and running by the end of the year.

Active Financing Exception (aka GE Loophole)

Subpart F of the tax code attempts to bar American corporations from deferring (delaying) paying U.S. taxes on certain types of offshore profits that are easily shifted out of the United States, such as interest income. The “active financing” exception to subpart F waives that rule for certain offshore financial business. The active financing exception should not be a part of the tax code.

The U.S. technically taxes worldwide corporate profits, but American corporations can defer (delay indefinitely) paying U.S. taxes on “active” profits of their offshore subsidiaries until those profits are officially brought to the U.S. “Active” profits are what most ordinary people would think of as profits earned directly from providing goods or services.

“Passive” profits, in contrast, include dividends, rents, royalties, interest and other types of income that are easier to shift from one subsidiary to another. Subpart F tries to bar deferral of taxes on such kinds of offshore income. The so-called “active financing exception” makes an exception to this rule for profits generated by offshore financial subsidiaries doing business with offshore customers.

The active financing exception was repealed in the loophole-closing1986 Tax Reform Act, but was reinstated in 1997 as a “temporary” measure after fierce lobbying by multinational corporations. President Clinton tried to kill the provision with a line-item veto; however, the Supreme Court ruled the line-item veto unconstitutional and reinstated the exception. In 1998 it was expanded to include foreign captive insurance subsidiaries. It has been extended numerous times since 1998, usually for only one or two years at a time, as part of the tax extenders.

As explained in a report from Citizens for Tax Justice, the active financing exception provides a tax advantage for expanding operations abroad. It also allows multinational corporations to avoid tax on their worldwide income by creating “captive” foreign financing and insurance subsidiaries.[10] The financial products of these subsidiaries, in addition to being highly fungible and highly mobile, are also highly susceptible to manipulation or “financial engineering,” allowing companies to manipulate their tax bill as well.

As the report explains, the exception is one of the reasons General Electric paid, on average, only a 1.8 percent effective U.S. federal income tax rate over ten years. G.E.’s federal tax bill is lowered dramatically with the use of the active financing exception provision by its subsidiary, G.E. Capital, which Forbes noted has an “uncanny ability to lose lots of money in the U.S. and make lots of money overseas.”[11]

Exclusion of Mortgage Debt Forgiveness

The exclusion of mortgage debt forgiveness waives the normal rule that canceled debt is income that is taxable just as any other income, in the case of homeowners who have received debt relief in the wake of the housing recession.

Under the normal tax rules, when a person takes out a loan and that loan is then forgiven, the cancelled debt is considered income and is taxable like any other kind of income. If loan forgiveness was not counted as income, then a person making $50,000 a year would simply ask his employer to change the form of compensation to a $50,000 annual loan that would be forgiven. Anyone would be able to avoid taxes this way and the tax system would break down.

However, with the Mortgage Forgiveness Debt Relief Act of 2007 Congress made a temporary exception to this rule, and has extended that exception several times since then. Mortgage modifications or restructures provided by lenders are one source of relief to borrowers struggling to make payments. Congress decided that this relief would be more effective if the canceled debt was not taxed.

The provision allows taxpayers to exclude up to $2 million in mortgage debt forgiven on a primary residence from income for tax purposes.

Deduction for State and Local Sales Taxes

Permanent provisions in the federal personal income tax allow taxpayers to claim itemized deductions for property taxes and income taxes paid to state and local governments. Long ago, a deduction was allowed for state and local sales taxes, but that was repealed as part of the 1986 tax reform. In 2004, the deduction for sales taxes was brought back temporarily and extended several times since then.

Because the deduction for state and local sales taxes cannot be taken along with the deduction for state and local income taxes, in most cases, taxpayers will take the sales tax deduction only if they live in one of the handful of states that have no state income tax.

Taxpayers can keep their receipts to substantiate the amount of sales taxes paid throughout the year, but in practice most people use rough calculations provided by the IRS for their state and income level. People who make a large purchase, such as a vehicle or boat, can add the tax on such purchases to the IRS calculated amount.

There are currently nine states that have no broad-based personal income tax and rely more on sales taxes to fund public services. Politicians from these states argue that it’s unfair for the federal government to allow a deduction for state income taxes, but not for sales taxes. But this misses the larger point. Sales taxes are inherently regressive and this deduction cannot remedy that since it is itself regressive.

To be sure, lower-income people pay a much higher percentage of their incomes in sales taxes than the wealthy. But lower-income people also are unlikely to itemize deductions and are thus less likely to enjoy this tax break. In fact, the higher your income, the more the deduction is worth, since the amount of tax savings depends on your tax bracket.

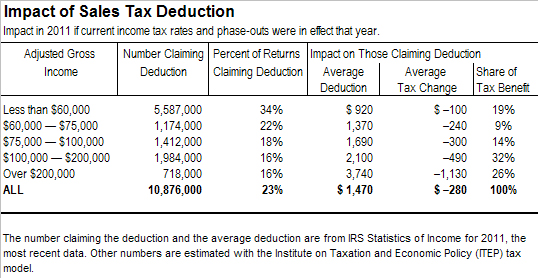

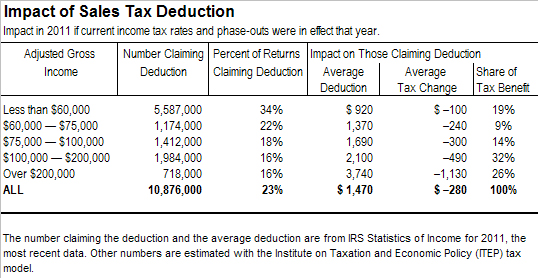

The table above includes taxpayer data from the IRS for 2011, the most recent year available, along with data generated from the Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy (ITEP) tax model to determine how different income groups would be affected by the deduction for sales taxes in the context of the federal income tax laws in effect today.

As illustrated in the table, people making less than $60,000 a year who take the sales-tax deduction receive an average tax break of just $100, and receive less than a fifth of the total tax benefit. Those with incomes between $100,000 and $200,000 enjoy a break of almost $500 and receive a third of the deduction, while those with incomes exceeding $200,000 save $1,130 and receive just over a fourth of the total tax benefit.

15-Year Cost Recovery Break for Leasehold, Restaurants, and Retail

Congress has showered businesses with all sorts of depreciation breaks, which allow them to deduct the cost of developing capital assets more quickly than they actually wear out. This particular tax extender allows certain businesses to write off the cost of improvements made to restaurants and stores over 15 years rather than the 39 years that would normally be required.

It is unclear why helping restaurant owners and store owners improve their properties should be seen as more important than nutrition and education for low-income children or unemployment assistance or any of the other benefits that lawmakers insist cannot be enacted if they increase the deficit.

Depreciation Breaks for Smaller Businesses (Section 179 Expensing)

Section 179, a depreciation break, allows smaller businesses to write off most of their capital investments immediately (up to certain limits).

A report from the Congressional Research Service reviews efforts to quantify the impact of depreciation breaks and explains that “the studies concluded that accelerated depreciation in general is a relatively ineffective tool for stimulating the economy.”[12]

One positive thing that can be said about section 179 is that it is more targeted towards small business investment than any of the other tax breaks that are alleged to help small businesses.

Section 179 allows firms to deduct the entire cost of a capital purchase (to “expense” the cost of a capital purchase) up to a limit. The provision allows expensing of up to $500,000 of purchases of certain capital investments (generally, equipment but not land or buildings). The deduction is reduced a dollar for each dollar of capital purchases exceeding $2 million, and the total amount expensed cannot exceed the business income of the taxpayer.

These limits mean that section 179 generally does not benefit large corporations like General Electric or Boeing, even if the actual beneficiaries are not necessarily what ordinary people think of as “small businesses.”

There is little reason to believe that business owners, big or small, respond to anything other than demand for their products and services. But to the extent that a tax break could possibly prod small businesses to invest, section 179 is somewhat targeted to accomplish that goal.

Work Opportunity Tax Credit

The Work Opportunity Tax Credit ostensibly helps businesses hire welfare recipients and other disadvantaged individuals. But a report from the Center for Law and Social Policy concludes that it mainly provides a tax break to businesses for hiring they would have done anyway:[13]

WOTC is not designed to promote net job creation, and there is no evidence that it does so. The program is designed to encourage employers to increase hiring of members of certain disadvantaged groups, but studies have found that it has little effect on hiring choices or retention; it may have modest positive effects on the earnings of qualifying workers at participating firms. Most of the benefit of the credit appears to go to large firms in high turnover, low-wage industries, many of whom use intermediaries to identify eligible workers and complete required paperwork. These findings suggest very high levels of windfall costs, in which employers receive the tax credit for hiring workers whom they would have hired in the absence of the credit.

Controlled Foreign Corporations Look-Through Rule (aka Apple Loophole)

Another exception to the general Subpart F rules requiring current taxation of passive income, the “CFC look-thru rules” allow a U.S. multinational corporation to defer tax on passive income, such as royalties, earned by a foreign subsidiary (a “controlled foreign corporation” or “CFC”) if the royalties are paid to that subsidiary by a related CFC and can be traced to the active income of the payer CFC.[14]

The closely watched Apple investigation by the Senate Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations a year ago resulted in a memorandum — signed by the subcommittee’s chairman and ranking member, Carl Levin and John McCain — that listed the CFC look-through rule as one of the loopholes used by Apple to shift profits abroad and avoid U.S. taxes.[15]

[1] Gary Guenther, “Section 179 and Bonus Depreciation Expensing Allowances: Current Law, Legislative Proposals in the 112th Congress, and Economic Effects,” September 10, 2012.

http://www.fas.org/sgp/crs/misc/RL31852.pdf

[2] Steve Wamhoff, “‘Research’ Tax Credit Used to Develop Soft Drink Flavors and Machines to Replace Workers,” Citizens for Tax Justice, November 20, 2014. http://www.taxjusticeblog.org/archive/2014/11/research_tax_credit_used_to_de.php

[3] Steve Wamhoff, “On Highway Bill, Congress Moves to the Right of Grover Norquist,” Citizens for Tax Justice, August 1, 2014. http://www.taxjusticeblog.org/archive/2014/08/on_highway_bill_congress_moves.php

[4] Citizens for Tax Justice, “Congress Is About to Shower More Tax Breaks on Corporations After Telling the Unemployed to Drop Dead,” February 14, 2014. http://www.taxjusticeblog.org/archive/2014/02/congress_is_about_to_shower_mo.php

[5] Citizens for Tax Justice, press statement, Out-of-Touch Congress Moves to Pass Deficit-Financed Corporate Tax Breaks, November 26, 2014. http://ctj.org/ctjreports/2014/11/press_statement_out-of-touch_congress_moves_to_pass_deficit-financed_corporate_tax_breaks.php

[6] Congressional Budget Office, “An Update to the Budget and Economic Outlook: 2014 to 2024,” August 27, 2014.

http://www.cbo.gov/publication/45653

[7] Gary Guenther, Section 179 and Bonus Depreciation Expensing Allowances: Current Law, Legislative Proposals in the 112th Congress, and Economic Effects, September 10, 2012. http://www.fas.org/sgp/crs/misc/RL31852.pdf

[8] Citizens for Tax Justice, “Reform the Research Credit — Or Let It Die,” December 4, 2013. http://ctj.org/ctjreports/2013/12/reform_the_research_tax_credit_–_or_let_it_die.php

[9] “Coalition to Congress: End the Wind Production Tax Credit,” September 24, 2013, http://www.eenews.net/assets/2013/09/24/document_pm_02.pdf; Nicolas Loris, “Let the Wind PTC Die Down Immediately,” October 8, 2013. http://www.heritage.org/research/reports/2013/10/wind-production-tax-credit-ptc-extension

[10] Citizens for Tax Justice, “Don’t Renew the Offshore Tax Loopholes,” August 2, 2012. www.ctj.org/ctjreports/2012/08/dont_renew_the_offshore_tax_loopholes.php

[11] Christopher Helman, “What the Top U.S. Companies Pay in Taxes,” Forbes, April 1, 2010, http://www.forbes.com/2010/04/01/ge-exxon-walmart-business-washington-corporate-taxes.html.

[12] Gary Guenther, “Section 179 and Bonus Depreciation Expensing Allowances: Current Law, Legislative Proposals in the 112th Congress, and Economic Effects,” Congressional Research Service, September 10, 2012. http://www.fas.org/sgp/crs/misc/RL31852.pdf

[13] Elizabeth Lower-Basch, “Rethinking Work Opportunity: From Tax Credits to Subsidized Job Placements,” Center for Law and Social Policy, November 2011. http://www.clasp.org/resources-and-publications/files/Big-Ideas-for-Job-Creation-Rethinking-Work-Opportunity.pdf

[14] Citizens for Tax Justice, “Don’t Renew the Offshore Tax Loopholes,” August 2, 2012. www.ctj.org/ctjreports/2012/08/dont_renew_the_offshore_tax_loopholes.php

[15] Senators Carl Levin and John McCain, Memorandum to Members of the Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations, May 21, 2013. http://www.hsgac.senate.gov/download/?id=CDE3652B-DA4E-4EE1-B841-AEAD48177DC4

![]()

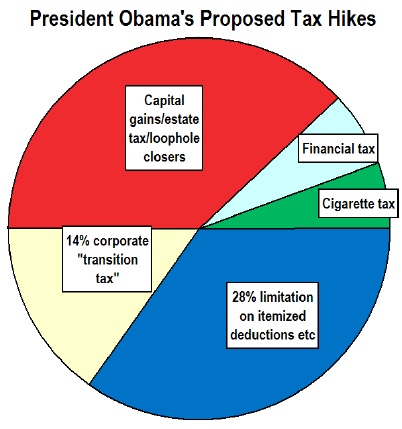

President Obama’s budget would raise about $1.7 trillion in new tax revenues over the next ten years.

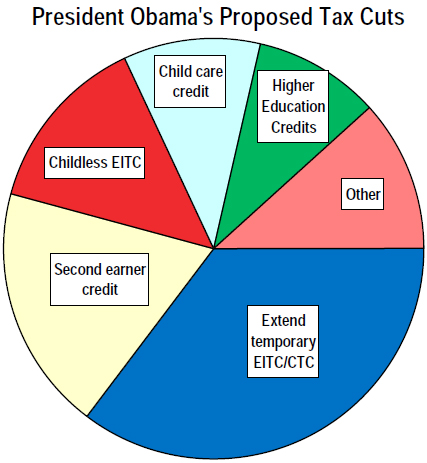

President Obama’s budget would raise about $1.7 trillion in new tax revenues over the next ten years. The president’s budget would use about a third of the revenues from his proposed tax increases to cut taxes. Almost all of these tax cuts are designed to benefit middle- and low-income working families.

The president’s budget would use about a third of the revenues from his proposed tax increases to cut taxes. Almost all of these tax cuts are designed to benefit middle- and low-income working families.

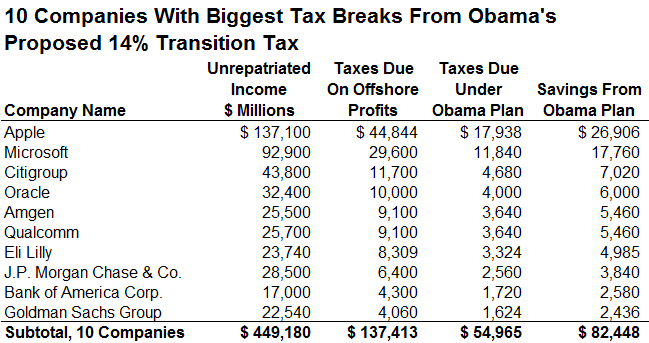

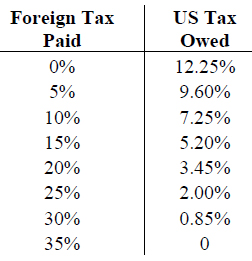

Delaney’s fallback proposal would end the deferral of U.S. taxes on offshore profits of American companies, but it would exempt a significant percentage of “active income” depending on the taxes, if any, already paid to foreign countries. For example, a companywith all of its offshore money in tax havens (with no tax paid) would pay the U.S. government only a 12.25 percent tax rate on its “active” foreign income. A company that paid a 25 percent rate on offshore income would owe the U.S. only 2 percent in taxes on “active” income. (See the table for a breakdown of the rate paid at different levels of foreign taxes.) For “passive” income, however, Delaney follows Baucus’s Option Z, and would not allow any exemption from the 35 percent U.S. corporate tax rate. “Passive income” includes income such as royalties that are very easy to shift into tax havens.

Delaney’s fallback proposal would end the deferral of U.S. taxes on offshore profits of American companies, but it would exempt a significant percentage of “active income” depending on the taxes, if any, already paid to foreign countries. For example, a companywith all of its offshore money in tax havens (with no tax paid) would pay the U.S. government only a 12.25 percent tax rate on its “active” foreign income. A company that paid a 25 percent rate on offshore income would owe the U.S. only 2 percent in taxes on “active” income. (See the table for a breakdown of the rate paid at different levels of foreign taxes.) For “passive” income, however, Delaney follows Baucus’s Option Z, and would not allow any exemption from the 35 percent U.S. corporate tax rate. “Passive income” includes income such as royalties that are very easy to shift into tax havens.