June 25, 2013 11:45 AM | Permalink |

Latest Proposed Tax Amnesty for Repatriated Offshore Profits Would Create Infrastructure Bank Run by Corporate Tax Dodgers

Read this report in PDF

Congressman John Delaney, a Democrat from Maryland, has proposed to allow American corporations to bring a limited amount of offshore profits back to the U.S. (to “repatriate” these profits) without paying the U.S. corporate tax that would normally be due. This type of tax amnesty for repatriated offshore profits is euphemistically called a “repatriation holiday” by its supporters. The Congressional Research Service has found that a similar proposal enacted in 2004 provided no benefit for the economy and that many of the corporations that participated actually reduced employment.[1]

Rep. Delaney seems to believe his bill (H.R. 2084) can avoid that unhappy result by allowing corporations to repatriate their offshore funds tax-free only if they also fund a bank that finances public infrastructure projects, which he believes would create jobs in America. As explained below, this is a strange and problematic way to fund infrastructure projects. In addition, Delaney’s bill will provide the greatest benefits to corporations that are engaging in accounting schemes to make their U.S. profits appear to be generated in offshore tax havens, further encouraging such tax avoidance and resulting in a revenue loss in the long-run. Incredibly, a super-majority of the infrastructure bank’s board of directors would, under Delaney’s bill, be chosen by the corporations that receive the most tax breaks.

“Offshore” Profits Are Not “Locked” Offshore

Some members of Congress, pundits and corporate lobbyists claim we need a tax amnesty to lure to the U.S. the $2 trillion of “permanently reinvested earnings” that American corporations hold in foreign subsidiaries. These are profits that U.S. corporations have generated (or claim to have generated) in foreign countries and on which they have not yet paid U.S. taxes. Proponents of a repatriation tax amnesty argue that forgiving the U.S. tax that is normally due when these profits are brought to the U.S. will get this money “back” into the U.S. economy.

But much, if not most of these “offshore” profits are actually already in the U.S. economy, and nothing prevents our corporations from using them to make investments here. A December 2011 study by the Senate Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations surveyed 27 corporations, including the 15 corporations that repatriated the most offshore cash under the 2004 law, and concluded that in 2010, 46 percent of the “permanently reinvested earnings” held offshore by these corporations were invested in U.S. assets like U.S. bank deposits, U.S. stocks, U.S. Treasury bonds and similar investments.[2] In other words, U.S. corporations are free to invest their funds in the U.S. economy.

The only thing corporations are unable to use their offshore cash for are dividends to their shareholders. But even this is allowed if the corporations simply pay the U.S. tax that is due — which is equal to the U.S. corporate income tax rate of 35 percent minus whatever the corporation has already paid to the government of the foreign country where the profits are said to be generated.

“Offshore” Profits Largely Represent Profits Generated in the U.S.

Some of these offshore profits really are generated in another country. For example, an American corporation may have a subsidiary in France that makes cars and sells them to French citizens, generating profits in France that the subsidiary there is likely to reinvest in its factories and other assets there.

But in many other situations, an American corporation generates profits in the U.S. but uses accounting gimmicks to tell the IRS that they are generated by a subsidiary in a country with no corporate tax or a very low corporate tax (an offshore tax haven). Often this subsidiary company carries out no actual business and consists of little more than a post office box.

How do we know that the profits our corporations claim to have generated in low-tax or no-tax countries do not represent any real business activity? Because most countries where Americans corporations are likely to carry out real business — countries like France, Germany, Japan and others with developed economies and consumers who buy our products — have a corporate tax. On the other hand, most of the countries with a very low corporate tax or no corporate tax are tiny economies that cannot be the location for very much legitimate business.

Luxembourg and Bermuda serve as two examples of tax havens. The Congressional Research Service recently found that the profits that American corporations claim (to the IRS) to have earned through their subsidiaries in Luxembourg in 2008 equaled 208 percent of that country’s gross domestic product (GDP). That’s another way of saying American corporations claim to have earnings in Luxembourg that are twice as large as that nation’s entire economy, which is obviously impossible. The profits that American corporations claimed to have earned through subsidiaries in Bermuda equaled 1000 percent of that tiny country’s economy.[3] It is clear that most of the profits American corporations claim are earned by their subsidiaries in these tax havens are not the result of any real business activity there.

Greatest Benefits of Tax Amnesty Go to the Worst Corporate Tax Dodgers

Unfortunately, the profits artificially shifted to offshore tax havens are the profits that American corporations are most likely to “repatriate” under the type of tax amnesty enacted in 2004 and under the measure proposed by Rep. Delaney. An October 2011 study by the Senate Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations surveyed 20 corporations, including the 15 that repatriated the most offshore funds under the 2004 measure, and found the following:

The data collected by the Subcommittee survey shows that a significant amount of the repatriated funds under Section 965 flowed from tax haven jurisdictions, including the Bahamas, Bermuda, British Virgin Islands, Cayman Islands, Costa Rica, Hong Kong, Ireland, Luxembourg, Netherlands Antilles, Panama, Singapore, and Switzerland. Of the 19 corporations surveyed, seven or 37% repatriated between 90 and 100% of funds from tax haven jurisdictions… Of the remaining 12 corporations surveyed by the Subcommittee, five repatriated from 70% to 89% of their funds from tax havens; three repatriated between 30 and 69% of their funds from tax havens; two repatriated around 7%; and two repatriated less than 1%.[4]

There are at least two reasons why profits artificially shifted into offshore tax havens are the most likely to be “repatriated” under this type of tax amnesty. First, the offshore profits that result from real business activity (like the profits generated by an American car manufacturer in France in the hypothetical example given above) are typically reinvested in factories or training the French workforce or in some other way. The U.S. corporation that owns that subsidiary in France cannot easily bring the “permanently reinvested earnings” back to the U.S. because that would require selling factory equipment or other similar assets.

But the “offshore” profits that are claimed to be generated by a subsidiary that is really just a post office box in a tax haven like Bermuda or Luxembourg are much easier to “move” because they don’t represent any real investments in the foreign country.

The second reason is that profits in tax havens get a bigger tax break when “repatriated” under such a tax amnesty. Again, the U.S. tax that is normally due on repatriated offshore profits is the U.S. corporate tax rate of 35 percent minus whatever was paid to the government of the foreign country. Profits that American companies claim to generate in tax havens are not taxed at all (or taxed very little) by the foreign government, so they might be subject to the full 35 percent U.S. rate upon repatriation — and thus receive the greatest break when the U.S. tax is called off.

The Proposal Will Encourage Corporations to Shift Even More Profits into Tax Havens, Causing Revenue Loss in the Long-Run

Rep. Delaney’s bill specifically states that part of the mission of the infrastructure bank’s board of directors is “to at all times make clear that no taxpayer money supports the AIF [the infrastructure bank] or ever will.” But the infrastructure bank will cost taxpayers, and it would be far more sensible to finance the infrastructure bank with traditional direct government spending.

To understand why, note that U.S. corporations have shifted profits offshore at a greater rate since the 2004 measure was enacted.[5] This means a greater amount of corporate profits are not subject to the U.S. corporate tax.

Indeed, in 2004, many critics argued that the measure, which temporarily taxed repatriated offshore corporate profits at a tiny rate of just 5.25 percent, would encourage corporations to artificially shift even more profits into tax havens in anticipation for the next “repatriation holiday” enacted by Congress.

This fear becomes particularly warranted if Congress demonstrates that it is willing to enact such measures multiple times less than a decade apart. In 2011, as some members of Congress discussed enacting a second repatriation tax amnesty like the 2004 measure, the non-partisan Joint Committee on Taxation (JCT) concluded that this would cost $79 billion over a ten-year period partly because it would encourage American corporations to artificially shift even more profits offshore in anticipation of the next tax amnesty.[6]

Delaney’s Proposed Infrastructure Bank Would Be Controlled by the Most Aggressive Corporate Tax Dodgers

There are some peculiar features of Rep. Delaney’s bill that lawmakers should consider. Rather than temporarily allowing American corporations to pay a corporate tax rate of just 5.25 percent on repatriated profits (as the 2004 measure did), Delaney’s proposal would temporarily tax repatriated profits at a rate of zero percent — if the corporation agreed to buy bonds to fund an infrastructure bank.

Corporations would be allowed to repatriate a certain number of dollars of offshore profits for each dollar it spends on purchasing bonds. The exact ratio would be determined by a bidding process, with the bonds (and the tax amnesty) going to those corporations offering the lowest bids. (The proposal would not allow bids for repatriation of more than six dollars in offshore profits for each dollar of bonds purchased.) The total amount of bonds issued to finance the bank would be $50 billion.

The bank would be controlled by a board of directors with 11 members. Four of those members would be appointed by the President and approved by the Senate. Delaney’s bill also instructs that the board would include “Seven additional members, appointed one each by the seven entities purchasing the largest amount of bonds….” Since the amount of bonds purchased would be linked to the amount of offshore profits a corporation repatriates, this means that those corporations that repatriate the most under the proposal would effectively control the board of directors and thus the infrastructure bank.

Because the profits most likely to be repatriated under the measure are those profits artificially shifted into offshore tax havens (as explained above) this means that the most aggressive corporate tax dodgers would effectively control the infrastructure bank.

Delaney’s Proposal Shows How Far We Are from Real Tax Reform

Perhaps the worst aspect of Rep. Delaney’s proposal is that it signals an obvious misunderstanding of, or indifference to, the fundamental problems with our corporate tax system, which is in desperate need of reform and which would become more dysfunctional under this proposal.

The main reason U.S. corporations have so much in “permanently reinvested earnings” offshore is the rule allowing American corporations to “defer” paying their U.S. taxes on those profits until they are repatriated. Deferral essentially provides a benefit for holding profits offshore, or at least convincing the IRS that they are offshore.

There is a broader debate taking place right now about how the tax system could be reformed to address this problem and several others. The most logical solution would be to repeal “deferral” so that U.S. corporations pay U.S. taxes on all their profits when they are earned (minus any corporate income taxes paid on these profits to foreign governments).

Many members of Congress, including the chairman of the House Ways and Means Committee, propose to move in the opposite direction and permanently exempt the offshore profits of U.S. corporations from U.S. taxes. This type of permanent exemption for offshore corporate profits is often called a “territorial” system, whereas a temporary exemption for offshore corporate profits is called a “repatriation holiday.”

We have argued elsewhere that if allowing American corporations to “defer” paying U.S. taxes on their offshore profits has encouraged them to shift jobs and profits offshore, then completely exempting these profits from U.S. taxes will logically increase those terrible incentives.[7]

This is true even if the exemption is a temporary one (a “repatriation holiday”), because corporations will come to expect it to be repeated. Even worse, corporate CEOs will understand that Congress is not even close to enacting a real tax reform that cracks down on offshore profit-shifting by corporations.

[1] Despite provisions that were supposed to require repatriated funds to be used for investment and job creation, the Congressional Research Service concluded that the offshore profits repatriated under the 2004 tax amnesty went to corporate shareholders and not towards job creation. In fact, many of the companies that benefited the most actually reduced their U.S. workforces. Donald J. Maples, Jane G. Gravelle, Congressional Research Service, “Tax Cuts on Repatriation Earnings as Economic Stimulus: An Economic Analysis,” May 27, 2011. https://ctj.sfo2.digitaloceanspaces.com/pdf/crs_repatriationholiday.pdf

[2] United States Senate, Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations, Committee on Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs, “Offshore Funds Located Onshore: Majority Staff Report Addendum,” December 14, 2011. http://www.hsgac.senate.gov/download/report-addendum_-psi-majority-staff-report-offshore-funds-located-onshore

[3] Mark P. Keightley, “An Analysis of Where American Companies Report Profits: Indications of Profit Shifting,” Congressional Research Service, January 18, 2013.

[4] United States Senate, Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations, Committee on Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs, “Repatriating Offshore Funds: 2004 Tax Windfall for Select Multinationals: Majority Staff Report,” October 11, 2011. http://www.hsgac.senate.gov/download/report-psi-majority-staff-report_-repatriating-offshore-funds-oct-2011

[5] Citizens for Tax Justice, “Data on Top 20 Corporations Using Repatriation Amnesty Calls into Question Claims of New Democrat Network,” August 26, 2011. http://ctj.org/ctjreports/2011/08/data_on_top_20_corporations_using_repatriation_amnesty_calls_into_question_claims_of_new_democrat_ne.php; Citizens for Tax Justice, “Apple, Microsoft and Eight Other Corporations Each Increased Their Offshore Profit Holdings by $5 Billion or More in 2012,” March 11, 2013, http://ctj.org/ctjreports/2013/03/apple_microsoft_and_eight_other_corporations_each_increased_their_offshore_profit_holdings_by_5_bill.php; Citizens for Tax Justice, “Apple Is Not Alone,” June 2, 2013. http://ctj.org/ctjreports/2013/06/apple_is_not_alone.php

[6] Letter from the Thomas A. Barthold, Joint Committee on Taxation to Congressman Lloyd Doggett, April 15, 2011. https://ctj.sfo2.digitaloceanspaces.com/pdf/jct_repatriationholiday.pdf.

[7] Citizens for Tax Justice, “Congress Should End ‘Deferral’ Rather than Adopt a ‘Territorial’ Tax System,” March 23, 2011. http://ctj.org/ctjreports/2011/03/congress_should_end_deferral_rather_than_adopt_a_territorial_tax_system.php

![]()

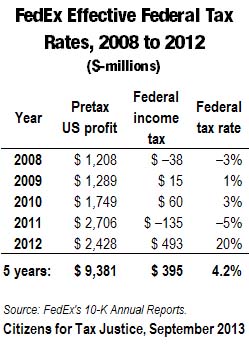

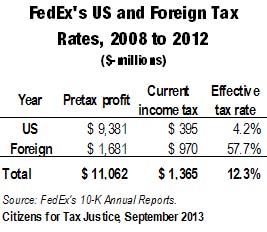

bstantially faster than they actually wear out, is the main reason for the company’s low taxes. Accelerated depreciation is a long-standing tax break that Congress has acted to expand substantially in the past decade.

bstantially faster than they actually wear out, is the main reason for the company’s low taxes. Accelerated depreciation is a long-standing tax break that Congress has acted to expand substantially in the past decade.

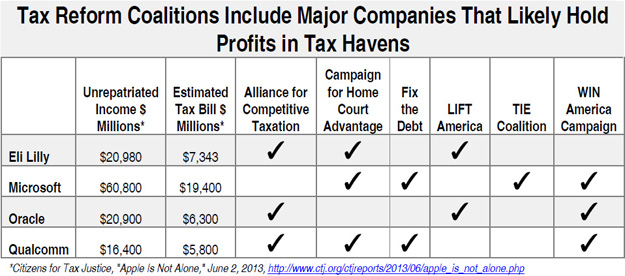

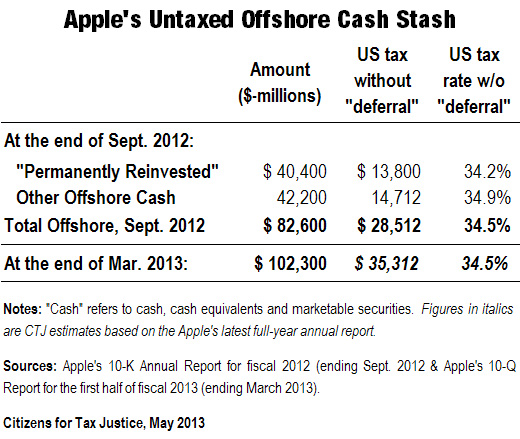

An analysis of Apple Inc.’s financial reports makes clear that Apple has paid almost no income taxes to any country on its $102 billion in offshore cash holdings. That means that this cash hoard reflects profits that were shifted, on paper, out of countries where the profits were actually earned into foreign tax havens.

An analysis of Apple Inc.’s financial reports makes clear that Apple has paid almost no income taxes to any country on its $102 billion in offshore cash holdings. That means that this cash hoard reflects profits that were shifted, on paper, out of countries where the profits were actually earned into foreign tax havens. annual report show that the company would pay almost the full 35 percent U.S. tax rate on its offshore income if repatriated. That means that virtually no tax has been paid on those profits to any government.

annual report show that the company would pay almost the full 35 percent U.S. tax rate on its offshore income if repatriated. That means that virtually no tax has been paid on those profits to any government.

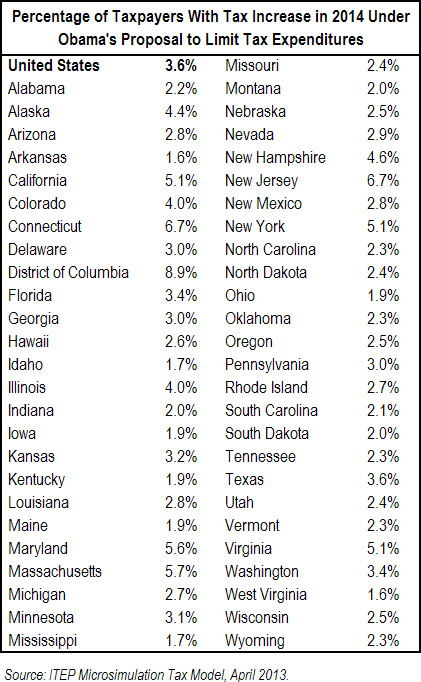

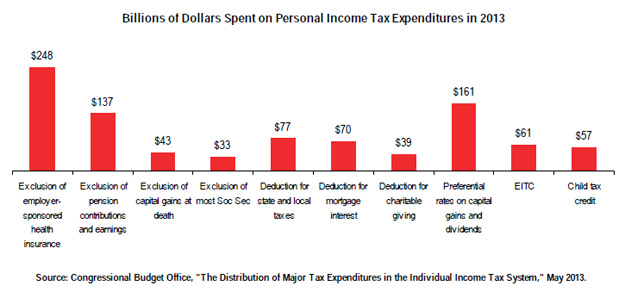

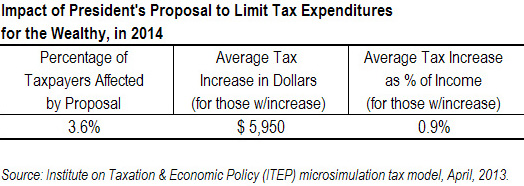

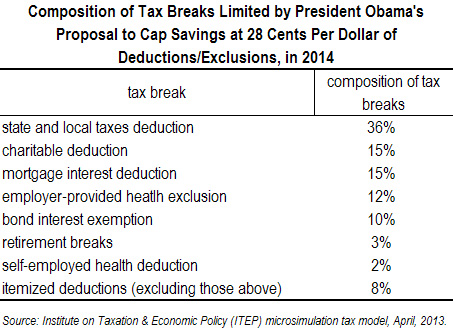

high-income person in the 39.6 percent income tax bracket saves almost 40 cents for each dollar of deductions or exclusions. An individual in the 35 percent income tax bracket saves 35 cents for each dollar of deductions or exclusions, and a person in the 33 percent bracket saves 33 cents. The lower tax rates are 28 percent or less. Many middle-income people are in the 15 percent tax bracket and therefore save only 15 cents for each dollar of deductions or exclusions.

high-income person in the 39.6 percent income tax bracket saves almost 40 cents for each dollar of deductions or exclusions. An individual in the 35 percent income tax bracket saves 35 cents for each dollar of deductions or exclusions, and a person in the 33 percent bracket saves 33 cents. The lower tax rates are 28 percent or less. Many middle-income people are in the 15 percent tax bracket and therefore save only 15 cents for each dollar of deductions or exclusions.