June 2, 2013 04:43 PM | Permalink | ![]()

Dell, Microsoft and Fifteen Other Fortune-500 Corporations’ Financial Reports Indicate Their Offshore Profits Are In Tax Havens; Hundreds More Likely Do the Same

Recent Congressional hearings on the international tax-avoidance strategies pursued by the Apple corporation documented the company’s strategy of shifting U.S. profits to offshore tax havens. But Apple is hardly the only major corporation that appears to be engaging in offshore-tax sheltering: seventeen other Fortune 500 corporations disclose information, in their financial reports, that strongly suggests they have paid little or no tax on their offshore holdings. It’s likely that hundreds of other Fortune 500 companies are also engaging in similar strategies to take advantage of the rule allowing U.S. companies to “defer” paying U.S. taxes on their offshore income.

How We Know When Multinationals’ Offshore Cash is Largely in Tax Havens

Under current law, corporations can indefinitely defer paying U.S. income taxes on their offshore profits. Multinational corporations with offshore profits sometimes disclose, in their financial reports, the amount of tax they would pay if there were no “deferral” and their offshore profits were taxable in the United States.[1] But this potential tax rarely amounts to the full 35 percent U.S. corporate tax rate, since these companies typically have already paid some foreign income taxes on these foreign profits when they were earned. Companies are allowed a “foreign tax credit” against their U.S. tax when and if the profits are subject to U.S. tax. So a company that has already paid (for example) a 25 percent tax rate on its offshore income would only pay the difference between that amount and the U.S. corporate tax rate of 35 percent (in this example, 10 percent) when that income is repatriated to the U.S.

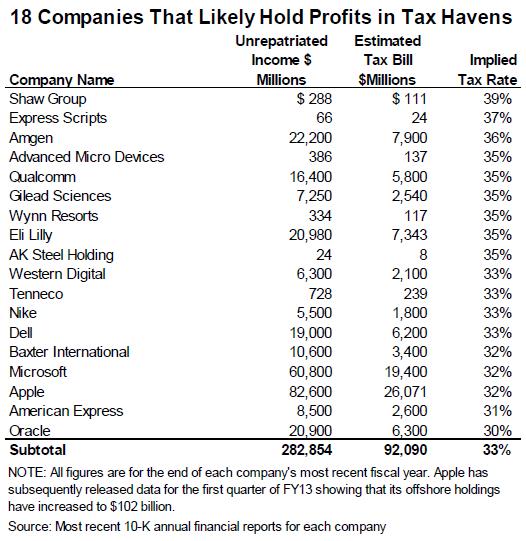

Apple is one of eighteen Fortune 500 companies that disclose, in their latest annual reports, that they would pay at least a 30 percent U.S. tax rate on their offshore income if repatriated. This figure is a clear indication that very little tax has been paid on those profits to any government—which in turn is an indicator that much of these offshore profits are being stashed in tax havens such as Bermuda and the Cayman Islands.

The table to the right shows the disclosures made by these eighteen corporations in their most recent annual financial reports. In particular:

- At the end of their most recent fiscal year, these companies collectively reported $283 billion in cash and cash equivalents parked offshore.

- Without “deferral,” however, these companies each estimate that they would pay a U.S. tax rate of at least 30 percent on their offshore stash—a clear indication that they have paid very little tax on these profits to any government.

- These companies include two of Apple’s competitors, Microsoft and Dell, but also include an array of other industries. Pharmaceutical giant Eli Lilly, the clothing manufacturer Nike, and the financial firm American Express all indicate that they would pay a tax rate of at least 30 percent on repatriation of their foreign profits.

Hundreds of Other Fortune 500 Corporations Don’t Disclose This Information

These 18 companies are not alone in shifting their profits to low-tax havens—they’re only alone in disclosing it. A total of 290 Fortune 500 corporations have disclosed, in their most recent financial reports, holding some of their income as “permanently reinvested” foreign profits. Yet the vast majority of these companies—235 out of 290—declined to disclose the U.S. tax rate they would pay if these offshore profits were repatriated. (55 corporations, including the 18 companies shown on this page, disclose this information. A full list of the 55 companies is published in the PDF of this report.) The non-disclosing companies collectively hold almost $1.3 trillion in unrepatriated offshore profits.

Accounting standards require publicly held companies to disclose the U.S. tax they would pay upon repatriation of their offshore profits—but these standards also provide a loophole allowing companies to assert that calculating this tax liability is “not practicable.” Almost all of the 235 non-disclosing companies use this loophole to avoid disclosing their likely tax rates upon repatriation—even though these companies almost certainly have the capacity to estimate these liabilities.

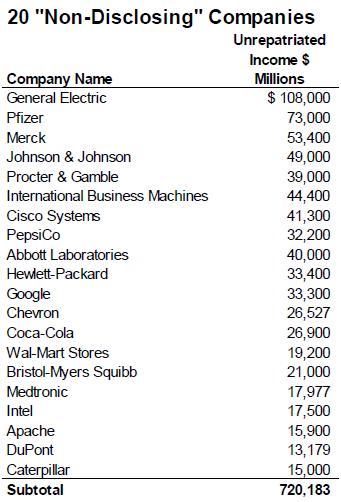

20 of the Biggest “Non-Disclosing” Companies Hold $720 Billion Offshore

The table at right shows the 20 non disclosing companies with the biggest offshore stash at the end of the most recent fiscal year. These 20 companies held $720 billion in unrepatriated offshore income—more than half of the total income held by the 235 “non-disclosing” companies. These companies also disclose, elsewhere in their financial reports, owning subsidiaries in known tax havens. For example:

- General Electric disclosed holding $108 billion offshore at the end of 2012. GE has subsidiaries in the Bahamas, Bermuda, Ireland and Singapore, but won’t disclose how much of its offshore cash is in these low-tax destinations. [Although some of it is clearly there; see text box below.]

- Pfizer has subsidiaries in Bermuda, the Cayman Islands, Ireland, the Isle of Jersey, Luxembourg and Singapore, but does not disclose how much of its $73 billion in offshore profits are stashed in these tax havens.

- Merck has 14 subsidiaries in Bermuda alone. It’s unclear how much of its $53 billion in offshore profits are being stored (for tax purposes) in this tiny island.

Hundreds of Billions in Tax Revenue at Stake

It’s impossible to know how much income tax would be paid, under current tax rates, upon repatriation by the 235 Fortune 500 companies that have disclosed holding profits overseas but have failed to disclose how much U.S. tax would be due if the profits were repatriated. But if these companies paid at the same 28 percent average tax rate as the 55 disclosing companies, the resulting one-time tax would total $363 billion for these 235 companies. Added to the $127 billion tax bill estimated by the 55 companies who did disclose, this means that taxing all the “permanently reinvested” foreign income of the 290 companies could result in almost $491 billion in added corporate tax revenue.

|

Even “Non-Disclosers” Slip Up Sometimes As noted above, General Electric does not disclose the US tax it would owe if its $108 billion offshore stash was repatriated. But in its 2009 annual report, GE noted that it had reclassified $2 billion of previously earned foreign profits as “permanently reinvested” offshore, and said that this change resulted “in an income tax benefit of $700 million.” Since $700 million is 35 percent of $2 billion, this is an admission that the expected foreign tax rate on this $2 billion of offshore cash was exactly zero, which in turn strongly suggests that GE’s “permanent reinvestment” plan for this $2 billion involved assigning it to one of its tax haven subsidiaries. |

What Should Be Done?

Many of the large multinationals that fail to disclose whether their offshore profits are stored in tax havens are the same companies that have lobbied heavily for tax breaks on their offshore cash. These companies propose either to enact a temporary “tax holiday” for repatriation, under which companies bringing offshore profits back to the U.S. would pay a very low tax rate on the repatriated income, or a permanent exemption for offshore income in the form of a “territorial” tax system. Either of these proposals would leave in place, or even increase, the incentive for multinationals to shift their U.S. profits, on paper, into tax havens.

A far more sensible solution would be to simply end “deferral,” repealing the rule that indefinitely exempts offshore profits from U.S. income tax until these profits are repatriated. Ending deferral would mean that all profits of U.S. corporations, whether they are generated in the U.S. or abroad, would be taxed by the United States. Of course, American corporations would continue to receive a “foreign tax credit” against any taxes they pay to foreign governments, to ensure that these profits are not double-taxed.

Conclusion

Long before the recent Congressional hearings on Apple’s tax avoidance, it was clear to many observers that U.S. multinational corporations are systematically sheltering income overseas. The limited disclosures made by Apple and a handful of other Fortune 500 corporations show that these companies have moved profits into tax havens—and that some of these companies have managed to avoid virtually all taxes on these profits. But the scope of this tax avoidance is likely much larger, since the vast majority of Fortune 500 companies with offshore cash refuse to disclose how much tax they would pay on repatriating their offshore profits.

Despite lobbying by large multinationals that refuse to disclose whether their offshore profits are in tax havens, lawmakers should resist calls for tax changes, such as repatriation holidays or a territorial tax system, that would keep in place the incentives encouraging U.S. companies to send their profits to tax havens. If the Securities and Exchange Commission required more complete disclosure about multinationals’ offshore profits, it would become obvious that Congress should end deferral, thereby eliminating the incentive for multinationals to shift their profits offshore once and for all.

[1] Publicly held corporations with permanently reinvested foreign earnings are obligated to either disclose the tax they would pay upon repatriation or state that they are unable to calculate this tax liability. Most corporations choose the latter option. Apple is one of 55 companies identified in this report that choose to estimate their potential tax liability.