July 8, 2014 03:08 PM | Permalink |

Read this report in PDF.

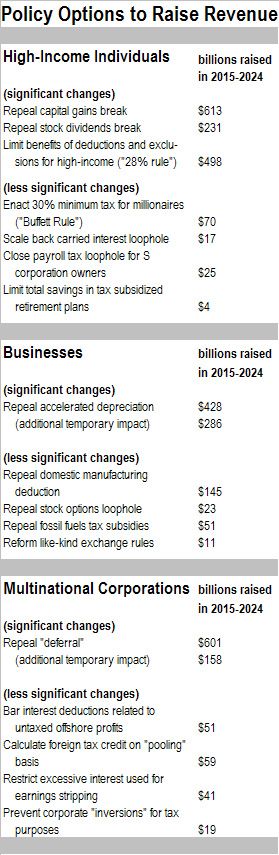

America is undertaxed, and the result is underfunding of public investments that would improve our economy and the overall welfare of Americans. Fortunately, Congress has several straightforward policy options to raise revenue, mostly by closing or limiting loopholes and special subsidies imbedded in the tax code that benefit wealthy individuals and profitable businesses.

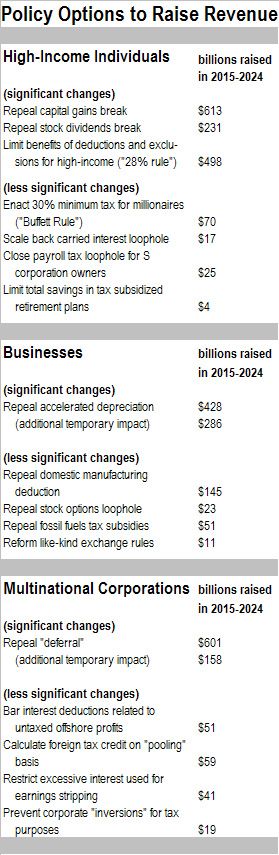

Part I of this report explains why Congress needs to raise the overall amount of federal revenue collected. Contrary to many politicians’ claims, the United States is much less taxed than other countries, and wealthy individuals and corporations are particularly undertaxed. This means that lawmakers should eschew enacting laws that reduce revenue (including the temporary tax breaks that Congress extends every couple of years), and they should proactively enact new legislation that increases revenue available for public investments. Parts II, III, and IV of this report describe several policy options that would accomplish this. This information is summarized in the table to the right.

Even when lawmakers agree that the tax code should be changed, they often disagree about how much change is necessary. Some lawmakers oppose altering one or two provisions in the tax code, advocating instead for Congress to enact such changes as part of a sweeping reform that overhauls the entire tax system. Others regard sweeping reform as too politically difficult and want Congress to instead look for small reforms that raise whatever revenue is necessary to fund given initiatives.

The table to the right illustrates options that are compatible with both approaches. Under each of the three categories of reforms, some provisions are significant, meaning they are likely to happen only as part of a comprehensive tax reform or another major piece of legislation. Others are less significant, would raise a relatively small amount of revenue, and could be enacted in isolation to offset the costs of increased investment in (for example) infrastructure, nutrition, health or education.

For example, in the category of reforms affecting high-income individuals, Congress could raise $613 billion over 10 years by eliminating an enormous break in the personal income tax for capital gains income. This tax break allows wealthy investors like Warren Buffett to pay taxes at lower effective rates than many middle-class people. Or Congress could raise just $17 billion by addressing a loophole that allows wealthy fund managers like Mitt Romney to characterize the “carried interest” they earn as “capital gains.” Or Congress could raise $25 billion over ten years by closing a loophole used by Newt Gingrich and John Edwards to characterize some of their earned income as unearned income to avoid payroll taxes.

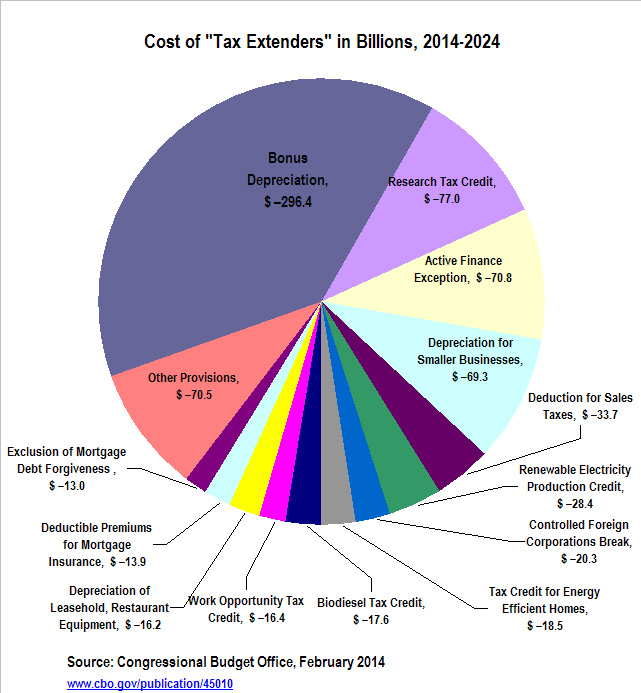

In the category of reforms affecting businesses, Congress could raise $428 billion by repealing accelerated depreciation. (This reform would also raise an additional $286 billion in the first decade, but this impact would be temporary.) Accelerated depreciation is the most significant break for domestic businesses and a major reason some companies can avoid paying taxes. Or Congress could take much less dramatic steps and repeal smaller breaks that benefits businesses, such as the domestic manufacturing deduction. Proponents of accelerated depreciation and the domestic manufacturing deduction claim that they encourage investment and job creation in the United States, but neither seems to be accomplishing this goal.

In the category of reforms affecting multinational corporations, Congress could raise $601 billion over 10 years by closing the huge loophole in the corporate income tax that allows U.S. corporations to indefinitely “defer” paying U.S. taxes on profits that they generate offshore or that appear to be generated offshore because of dodgy accounting methods. (This reform would also raise an additional $158 billion in the first decade, but this impact would be temporary.) Or Congress could raise smaller amounts of revenue by curbing the worst abuses of deferral. President Obama has put forward several proposals to do this by closing loopholes in the deferral rules, and several of these proposals have been introduced as legislation by members of Congress.

These are just a few examples among many that are described in more detail in this report.

I. Why Congress Should Raise Revenue

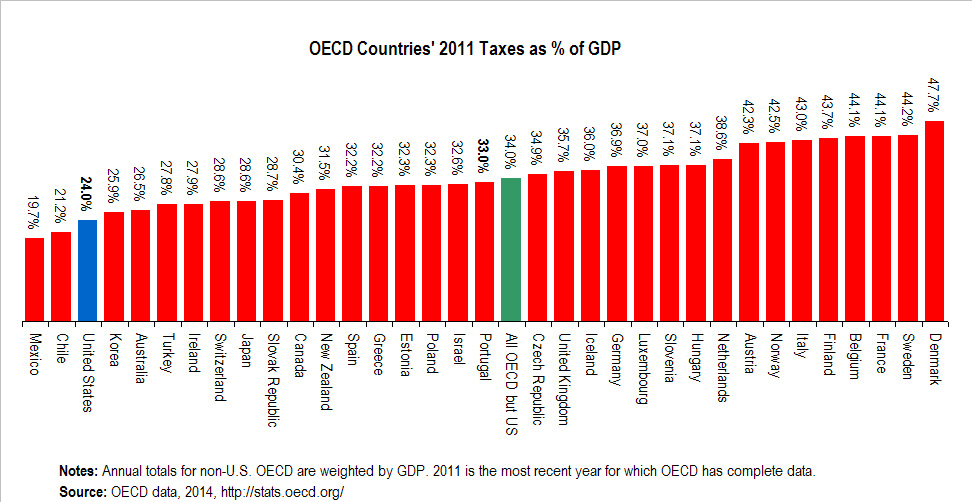

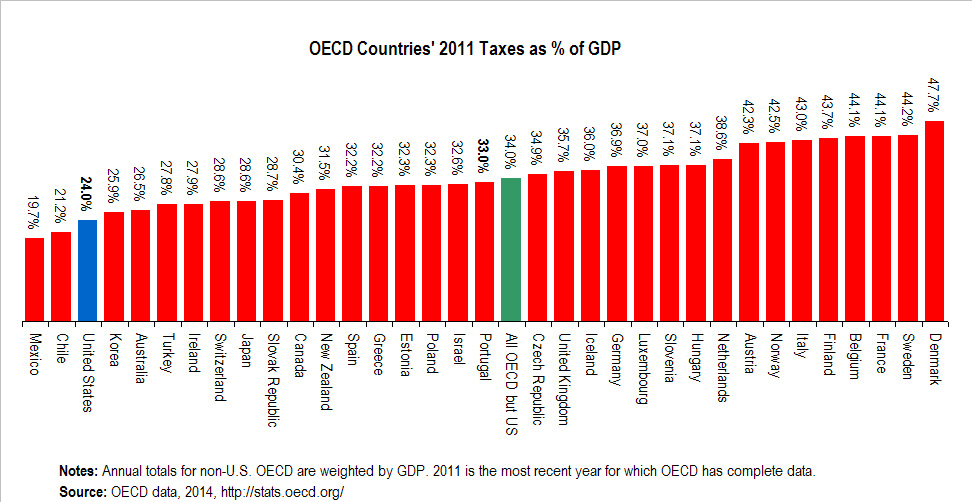

America Is Not Overtaxed

The belief that Americans pay too much, rather than too little, in taxes has so permeated our society that Microsoft Word’s spellchecker recognizes the word “overtaxed” but not its obvious antonym, “undertaxed.” As a result, some anti-government activists and politicians insist that no tax loopholes should be closed unless tax rates are also reduced so that the net result is no increase in federal revenue. This approach is entirely unwarranted, because America is actually one of the least taxed countries in the developed world. According to the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), the Unites States collects less tax revenue as a percentage of gross domestic product than all but two other industrial countries (Chile and Mexico), as illustrated in the graph below.[1]

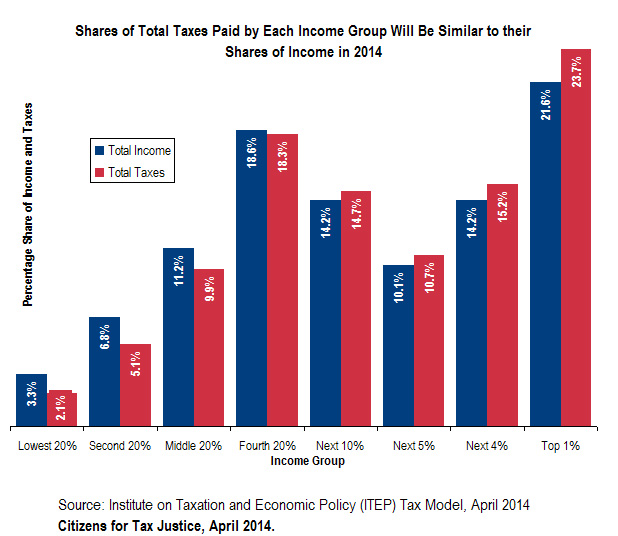

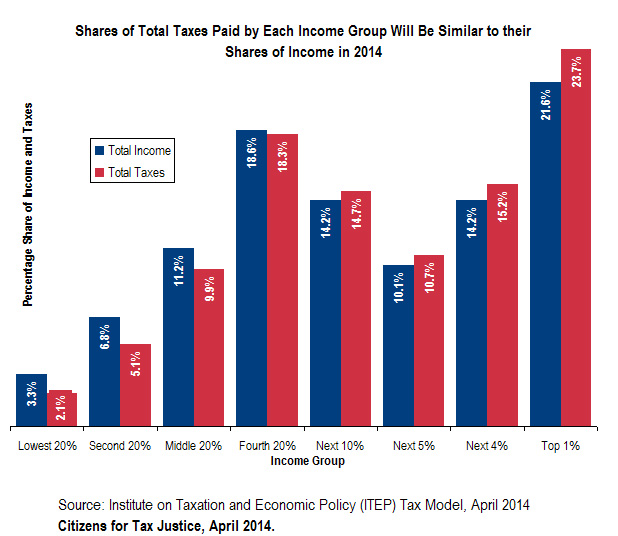

Wealthy Individuals Are Not Overtaxed

Another anti-tax argument is that the richest 1 percent or richest 5 percent of Americans are already paying more than their fair share of taxes, but this is also false. America’s tax system is just barely progressive, meaning it does very little to address the growing income inequality our nation has experienced over the last several decades.[2] The share of total taxes paid by each income group is very similar to the share of total income received by each group.

For example, the share of total taxes (including federal, state and local taxes) paid by the richest 1 percent (23.7 percent) is not significantly different from the share of total income this group receives (21.6 percent). Similarly, the share of total taxes paid by the poorest fifth (2.1 percent) is only slightly lower than the share of total income this group receives (3.3 percent).

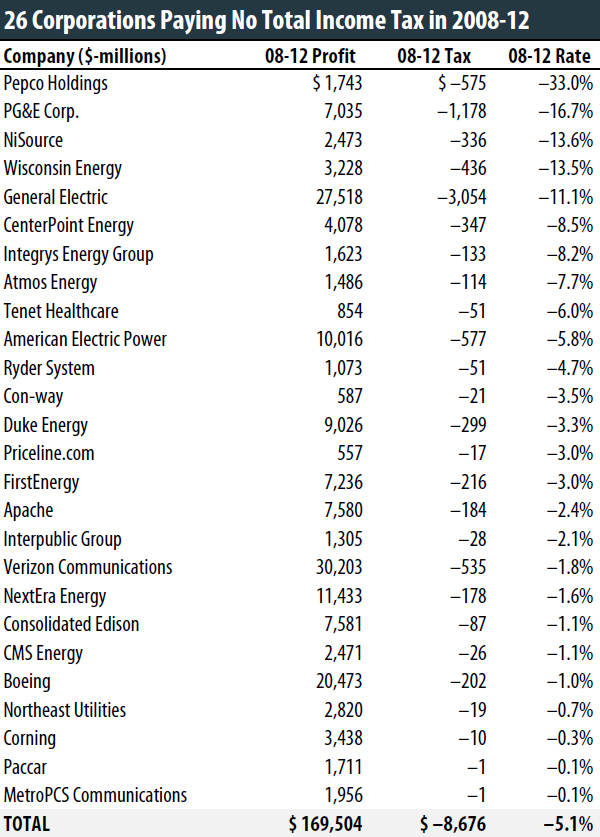

Corporations Are Not Overtaxed

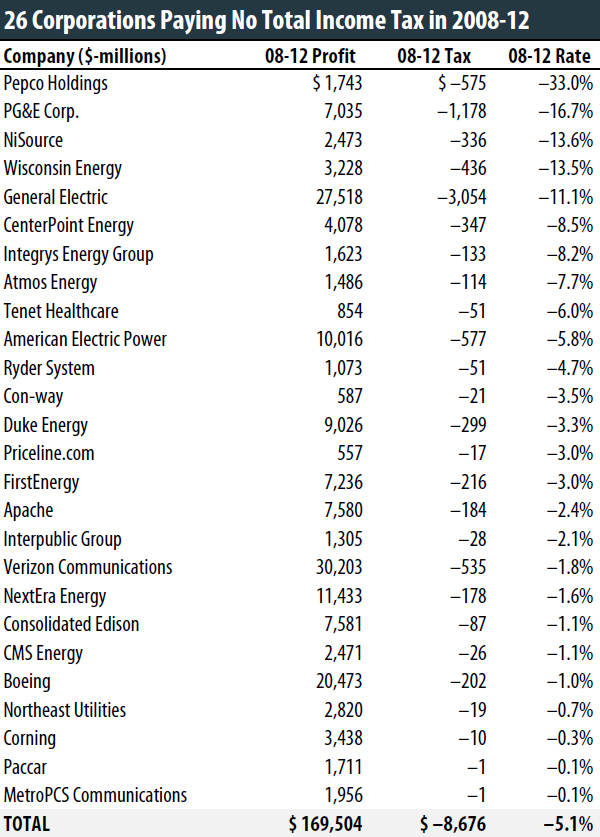

Some corporate lobbyists complain that the 35 percent U.S. statutory corporate income tax rate is one of the highest in the word. They fail to mention that the effective corporate income tax rate, the percentage of profits that corporations actually pay, is far lower due to loopholes that reduce their taxes. In fact, some corporate profits are not taxed at all. A recent report from CTJ examined 288 corporations (most of the Fortune 500 corporations that were profitable each year from 2008 through 2012) and found that over that five-year period they collectively paid 19.4 percent of their profits in federal corporate income taxes, and 26 of these companies paid nothing at all over that period.[3]

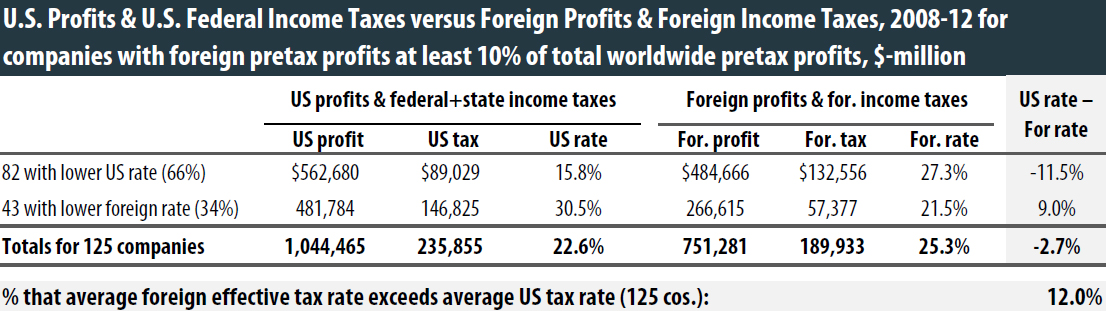

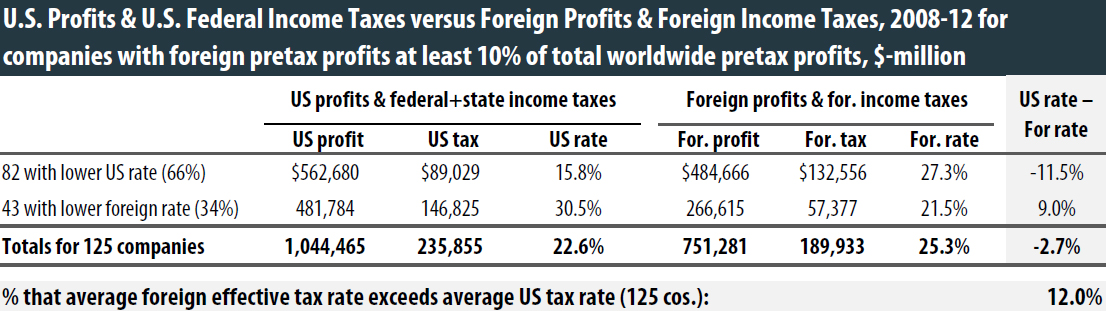

Corporate CEOs and their lobbyists often argue that the federal corporate income tax makes the nation “uncompetitive” because it causes companies not to invest in the United States, but this claim is not borne out by evidence. The CTJ study found that of those corporations with significant offshore profits (meaning at least one-tenth of profits were reported to be earned offshore) about two-thirds paid higher effective corporate income tax rates in the other countries where they did business than they paid in the U.S.

Of course, corporate income taxes are ultimately borne by human beings — primarily the corporate shareholders and owners of business assets, who are concentrated among the wealthiest Americans. As already explained, the richest Americans are not overtaxed, even when you account for all of the taxes, including corporate income taxes, that they ultimately pay.

Some opponents of higher corporate taxes have recently argued that the corporate income tax actually is borne by workers because it chases investment out of the United States and leaves working people with fewer job opportunities and lower wages. But corporate investment is not perfectly mobile and as a result, Congress’s non-partisan Joint Committee on Taxation has concluded that 82 percent of the corporate income tax is paid by owners of corporate stocks and other business assets.[4]

II. Revenue Options Affecting High-Income Individuals

Eliminate the special low income tax rates for capital gains

10-year revenue gain: $613 billion[5]

The federal personal income tax currently taxes the income of people who live off their wealth at lower rates than the income of people who work. This is particularly problematic because income from wealth (investment income) is largely concentrated among the richest Americans.

The unfairness of the existing preference for capital gains can best be illustrated with an example. Imagine an heiress who owns so much stock and other assets that she does not have to work. When she sells assets (through her broker) for more than their original purchase price, she enjoys the profit, which is called a capital gain. (Most of these gains are long-term capital gains, which we often refer to as “capital gains” for simplicity.) On this income she pays tax rate of only 23.8 percent. (This includes the personal income tax at a rate of 20 percent and a tax enacted as part of health care reform at a rate of 3.8 percent.)

Now consider a receptionist who works at the brokerage firm that handles some of the heiress’s dealings. Let’s say this receptionist earns $50,000 a year. Unlike the heiress, his income comes in the form of wages, because, alas, he has to work for a living. His wages are taxed at progressive income tax rates, and a portion of his income is actually taxed at 25 percent. (In other words, he faces a marginal income tax rate of 25 percent, meaning each additional dollar he earns is taxed at that amount).

Now consider a receptionist who works at the brokerage firm that handles some of the heiress’s dealings. Let’s say this receptionist earns $50,000 a year. Unlike the heiress, his income comes in the form of wages, because, alas, he has to work for a living. His wages are taxed at progressive income tax rates, and a portion of his income is actually taxed at 25 percent. (In other words, he faces a marginal income tax rate of 25 percent, meaning each additional dollar he earns is taxed at that amount).

On top of that, he also pays the federal payroll tax of around 15 percent. (He pays only half of the payroll tax directly, while his employer directly pays the other half, but economists generally agree that the full tax is ultimately borne by the employee in the form of reduced compensation.) So he pays taxes on his income at a higher rate than the heiress who lives off her wealth.

What makes this situation even worse are the various loopholes that allow wealthy individuals to receive these tax breaks for income that is not really even capital gains. As Warren Buffett has explained, fund managers use the “carried interest” loophole to have their compensation treated as capital gains and taxed at the low 20 percent rate, while the “60/40 rule” benefits traders who “own stock index futures for 10 minutes and have 60 percent of their gain taxed at 15 percent [now 20 percent], as if they’d been long-term investors.”[6]

The tax reform signed into law by President Reagan in 1986 eliminated such preferences for investment income from the personal income tax and taxed all income at the same rates. During the administrations of George H.W. Bush and Bill Clinton, Congress raised rates on “ordinary” income (income that does not take the form of long-term capital gains) but reduced the rates for capital gains in 1997.

When George W. Bush took office, the top tax rate on long-term capital gains was 20 percent, and the tax changes he signed into law in 2003 reduced that top rate to 15 percent. At the start of 2013, Congress extended most of the Bush-era tax cuts but allowed the top 20 percent tax rate for capital gains to come back into effect for the richest Americans.

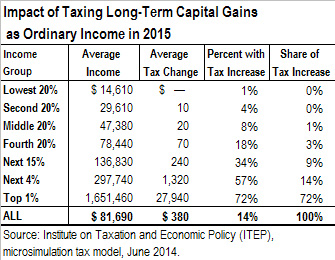

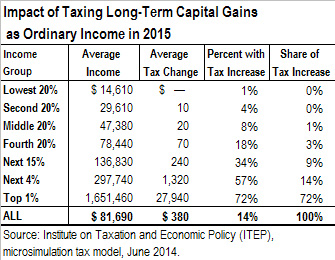

Congress should go much further and repeal the capital gains break that still exists. Under this proposal, capital gains would simply be taxed at ordinary income tax rates. This would raise at least $613 billion over a decade. The table on the previous page shows that the richest 1 percent of taxpayers would pay 72 percent of the tax increase resulting from eliminating the capital gains preference in 2015, and the richest 5 percent of taxpayers would pay 86 percent of the tax increase.

Some commentators, including The Wall Street Journal editorial board and many anti-tax activists, claim that if the income tax rate for capital gains reaches a certain point, investors will respond by selling assets less often and the revenue yield from the tax will be reduced as a result. They often claim that these behavioral responses are so strong that tax revenue will actually decrease if Congress raises the tax rate for capital gains, and revenue will actually increase if Congress reduces the tax rate.[7]

The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) and the Joint Committee on Taxation (JCT) also assume that this behavioral response exists, to a lesser but still significant degree. It is likely that if JCT estimated the revenue impact of eliminating the income tax preferences for capital gains, they would assume that these behavioral responses limit the amount of revenue raised to a much smaller figure than we calculate.[8]

We agree with the conclusion of the Congressional Research Service that JCT likely overestimates these behavioral responses and therefore underestimates how much revenue will result from raising income tax rates on capital gains.[9] It seems that people with investments do respond to changes in capital gains rates mostly in the short-term, but JCT relies on research that seems to mistake much of the short-term responses for long-term changes in investment behavior.

A previous CTJ report explains this in detail and explains that we use JCT’s methodology to quantify the way investors respond to tax changes, but we assume smaller behavioral responses based on rigorous studies cited and analyzed by the Congressional Research Service.[10]

Eliminate the special low income tax rates for stock dividends

10-year revenue gain: $231 billion[11]

Corporate stock dividends are subject to the same special low rates as capital gains, which provide another unjustified break that mostly goes to the well-off. Lawmakers introduced this break as part of 2003 legislation enacted under President Bush, which taxed both capital gains and stock dividends at a top rate of 15 percent. The 2013 legislation that extended most, but not all, of the Bush-era tax cuts allowed the top rate for dividends and capital gains both to rise to 20 percent for the richest Americans.

The unfairness of the dividends tax preference is straightforward. The wealthy heiress in the example above who lives off her wealth would likely receive income in the form of stock dividends just as she receives income in the form of capital gains, and in both cases she is taxed much less than someone who works to earn the same (or a much lower) amount of income.

The unfairness of the dividends tax preference is straightforward. The wealthy heiress in the example above who lives off her wealth would likely receive income in the form of stock dividends just as she receives income in the form of capital gains, and in both cases she is taxed much less than someone who works to earn the same (or a much lower) amount of income.

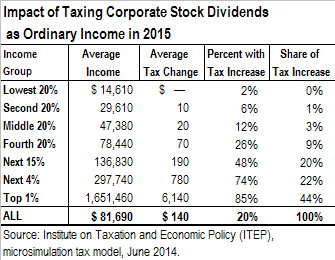

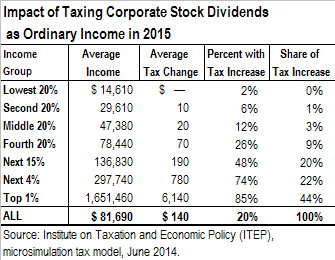

The table to the right shows that two-thirds of the tax increase resulting from taxing stock dividends as ordinary income would be paid by the richest 5 percent of taxpayers.

Some corporate lobbyists have argued that taxing stock dividends at higher rates (at the same rates as other types of income) would cause corporations to pay out less in dividends, which would harm all investors. The gaping hole in this logic is that two-thirds of stock dividends are not paid to individuals subject to the personal income tax but rather are paid to tax-exempt entities like pension funds.[12] There is no reason why stock prices would be affected by a tax that only applies to one-third of the dividends paid on them.

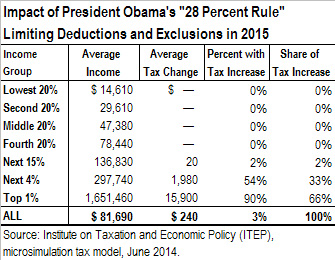

Limit certain deductions and exclusions for the wealthy (President Obama’s “28 Percent Rule”)

10-year revenue gain: $498 billion[13]

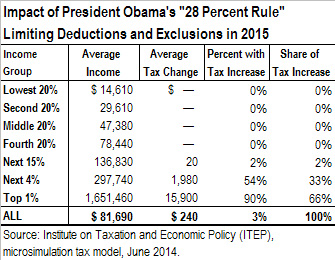

This proposal, often called the “28 percent rule,” would limit tax savings for high-income taxpayers from itemized deductions and certain other deductions and exclusions to 28 cents for each dollar deducted or excluded. If this reform was in effect in 2015, it would result in a tax increase for only 3.3 percent of Americans.

This proposal, which was offered in different forms over the past several years by President Obama, is a way of limiting tax expenditures for the wealthy. The term “tax expenditures” refers to provisions that are government subsidies provided through the tax code. As such, tax expenditures have the same effect as direct spending subsidies, because the Treasury ends up with less revenue and some individual or group receives money. But tax subsidies are sometimes not recognized as spending programs because they are implemented through the tax code.

Tax expenditures that take the form of deductions and exclusions are used to subsidize all sorts of activities. For example, deductions allowed for charitable contributions and mortgage interest payments subsidize philanthropy and home ownership. Exclusions for interest from state and local bonds subsidize lending to state and local governments.

Under current law, three income tax brackets have rates higher than 28 percent (the 33, 35, and 39.6 percent brackets). People in these tax brackets (and people who would be in these tax brackets if not for their deductions and exclusions) could therefore lose some tax breaks under the proposal.

Currently, a high-income person in the 39.6 percent income tax bracket saves almost 40 cents for each dollar of deductions or exclusions. An individual in the 35 percent income tax bracket saves 35 cents for each dollar of deductions or exclusions, and a person in the 33 percent bracket saves 33 cents. The lower tax rates are 28 percent or less. Many middle-income people are in the 15 percent tax bracket and therefore save only 15 cents for each dollar of deductions or exclusions.

This is an odd way to subsidize activities that Congress favors. If Congress provided such subsidies through direct spending, there would likely be a public outcry over the fact that rich people are subsidized at higher rates than low- and middle-income people. But because these subsidies are provided through the tax code, this fact has largely escaped the public’s attention.

This is an odd way to subsidize activities that Congress favors. If Congress provided such subsidies through direct spending, there would likely be a public outcry over the fact that rich people are subsidized at higher rates than low- and middle-income people. But because these subsidies are provided through the tax code, this fact has largely escaped the public’s attention.

President Obama initially presented his proposal to limit certain tax expenditures in his first budget plan in 2009, and included it in subsequent budget and deficit-reduction plans each year after. The original proposal applied only to itemized deductions. The President later expanded the proposal to limit the value of certain “above-the-line” deductions (which can be claimed by taxpayers who do not itemize), such as the deduction for health insurance for the self-employed and the deduction for contributions to individual retirement accounts (IRA).

More recently, the proposal was also expanded to include certain tax exclusions, such as the exclusion for interest on state and local bonds and the exclusion for employer-provided health care. Exclusions provide the same sort of benefit as deductions, the only difference being that they are not counted as part of a taxpayer’s income in the first place (and therefore do not need to be deducted).

Minimum 30 percent tax for millionaires to implement the “Buffett Rule”

10-year revenue gain: $70 billion[14]

The “Buffett Rule” began as a principle, proposed by President Obama, that the tax system should be reformed to reduce or eliminate situations in which millionaires pay lower effective tax rates than many middle-income people. This principle was inspired by billionaire investor Warren Buffett, who declared publicly that it was a travesty that his effective tax rate is lower than his secretary’s.

At the time, Citizens for Tax Justice argued that the most straightforward way to implement this principle would be to eliminate the special low personal income tax rate for capital gains and stock dividends (the main reason why wealthy investors like Mitt Romney and Warren Buffett can pay low effective tax rates) and tax all income at the same rates.[15]

The proposal offered by President Obama in his most recent budget plan and by Senate Democrats to fund a recent student loan proposal would implement the Buffett Rule in a more round-about way by applying a minimum tax of 30 percent to millionaires’ income. This would raise much less revenue than simply ending the break for capital gains and dividends, for several reasons.

First, taxing capital gains and dividends as ordinary income would subject them to a top income tax rate of 39.6 percent while the proposed minimum tax would have a rate of just 30 percent. Second, the proposed minimum income tax rate on capital gains and dividend income would effectively be less than 30 percent because it would take into account the 3.8 percent Medicare tax on investment income that was enacted as part of health care reform. Third, even though most capital gains and dividend income goes to the richest one percent of taxpayers, there is still a great deal that goes to taxpayers who are among the richest five percent or even one percent but are not millionaires and therefore not subject to the proposed minimum tax.

Other reasons for the lower revenue impact of this proposal (compared to repealing the preference for capital gains and dividends) have to do with how it is designed. For example, the minimum tax would be phased in for people with incomes between $1 million and $2 million. Otherwise, a person with adjusted gross income of $999,999 who has effective tax rate of 15 percent could make $2 more and see his effective tax rate shoot up to 30 percent. Tax rules are generally designed to avoid this kind of unreasonable result.

The legislation also accommodates those millionaires who give to charity by applying the minimum tax of 30 percent to adjusted gross income less charitable deductions.

Scale back the carried interest loophole

10-year revenue gain: $17 billion[16]

If Congress does not eliminate the tax preference for capital gains (as explained earlier) then it should at least eliminate the loopholes that allow the tax preference for income that is not truly capital gains. The most notorious of these loopholes is the one that allows “carried interest” to be taxed as capital gains.

Some businesses, primarily private equity, real estate and venture capital, use a technique called a “carried interest” to compensate their managers. Instead of receiving wages, the managers get a share of the profits from investments that they manage, without having to invest their own money. The tax effect of this arrangement is that the managers pay taxes on their compensation at the special, low rates for capital gains (up to 20 percent) instead of the ordinary income tax rates that normally apply to wages and other compensation (up to 39.6 percent). This arrangement also allows them to avoid payroll taxes, which apply to wages and salaries but not to capital gains.

Income in the form of carried interest can run into the hundreds of millions (or even in excess of a billion dollars) a year for individual fund managers. How do we know that “carried interest” is compensation, and not capital gain? There are several reasons:

The fund managers don’t invest their own money. They get a share of the profits in exchange for their financial expertise. If the fund loses money, the managers can walk away without any cost.[17]

A “carried interest” is much like executive stock options. When corporate executives get stock options, it gives them the right to buy their company’s stock at a fixed price. If the stock goes up in value, the executives can cash in the options and pocket the difference. If the stock declines, then the executives get nothing. But they never have a loss. When corporate executives make money from their stock options, they pay both income taxes at the regular rates and payroll taxes on their earnings.

Private equity managers (sometimes) even admit that “carried interest” is compensation. In a filing with the Securities and Exchange Commission in connection with taking its management partnership public, the Blackstone Group, a leading private equity firm, had this to say in 2007 about its activities (to avoid regulation under the Investment Act of 1940):

“We believe that we are engaged primarily in the business of asset management and financial advisory services and not in the business of investing, reinvesting, or trading in securities.

We also believe that the primary source of income from each of our businesses is properly characterized as income earned in exchange for the provision of services.”

The President has proposed to close the carried interest loophole, but his version of this proposal would only raise $17 billion over a decade, less than the version of the proposal he offered in his first budget plan, which was estimated to raise $23 billion over a decade.[18] The President’s current proposal now clarifies that only “investment partnerships,” as opposed to any other partnerships that provide services, would be affected.[19]

Close payroll tax loophole for S corporation owners (close the “John Edwards/Newt Gingrich Loophole”)

10-year revenue gain: $25 billion

This option would close a loophole that allows many self-employed people, infamously including two former lawmakers, John Edwards and Newt Gingrich, to use “S corporations” to avoid payroll taxes. Payroll taxes are supposed to be paid on income from work. The Social Security payroll tax is paid on the first $117,000 in earnings (adjusted each year) and the Medicare payroll tax is paid on all earnings. These rules are supposed to apply both to wage-earners and self-employed people.

“S corporations” are essentially partnerships, except that they enjoy limited liability, like regular corporations. The owners of both types of businesses are subject to income tax on their share of the profits, and there is no corporate level tax. But the tax laws treat owners of S corporations quite differently from partners when it comes to Social Security and Medicare taxes. Partners are subject to these taxes on all of their “active” income, while active S corporation owners pay these taxes only on the part of their “active” income that they report as wages. In effect, S corporation owners are allowed to determine what salary they would pay themselves if they treated themselves as employees.

Naturally, many S corporation owners likely make up a salary for themselves that is much less than their true work income in order to avoid Social Security payroll taxes and especially Medicare payroll taxes.[20]

Under this proposal, which was included in President Obama’s most recent budget plan, businesses providing professional services would be taxed the same way for payroll tax purposes regardless of whether they are structured as S corporations or partnerships.

Limit total savings in tax subsidized retirement plans

10-year revenue gain: $4 billion[21]

In 2013, Citizens for Tax Justice proposed that Congress limit the amount of savings that can accrue in individual retirement accounts (IRAs), which allow individuals to defer paying taxes on the income saved until retirement. [22] This was a response to reports that Mitt Romney had $87 million saved in an IRA, which was an obvious example of a tax subsidy meant to encourage retirement saving benefiting someone who did not need any such encouragement.

The budget plan released by the Obama administration later that year included this reform, as did the budget plan released this year.

Under current law, there are limits on how much an individual can contribute to tax-advantaged retirement savings vehicles like 401(k) plans or IRAs, but there is actually no limit on how much can be accumulated in such savings vehicles.

The contribution limit for IRAs is $5,500, adjusted each year, plus an additional $1,000 for people over age 50. It probably never occurred to many lawmakers that a buyout fund manager like Mitt Romney would somehow engineer a method to end up with tens of millions of dollars in his IRA.

The President proposes to essentially align the rules of 401(k)s and IRAs with the rules for “defined benefit” plans (traditional pensions). Under current law, in return for receiving tax advantages, defined benefit plans are subject to certain limits including a $210,000 annual limit on benefits paid out in retirement (adjusted each year). The President’s proposal would, very generally, limit contributions and accruals in all 401(k) plans and IRAs owned by an individual to whatever amount is necessary to pay out at that limit when the individual reaches retirement.

There seems to be great uncertainty over how exactly this proposal would work and how much revenue it would raise. This is not surprising given how difficult it is to predict how high-wealth individuals might manage to effectively transfer extremely undervalued assets into tax advantaged savings accounts, and how they might change their behavior in response to a legislative change. While the Joint Committee on Taxation estimates that the President’s proposal would raise $4 billion over a decade, the administration estimates that it would raise $28 billion over a decade.[23]

III. Revenue Options Affecting Businesses

Repeal accelerated depreciation

10-year revenue gain: $428 billion

(plus $286 billion temporary impact in the first decade)[24]

Businesses are allowed to deduct from their taxable income the expenses of running the business, so that what’s taxed is net profit. Businesses can also deduct the costs of purchases of machinery, software, buildings and so forth, but since these capital investments don’t lose value right away, these deductions are taken over time. The basic idea behind depreciation is that when a company makes a capital purchase of a piece of equipment, it can deduct the cost of that equipment over the period of time in which the equipment is thought to wear out.

Accelerated depreciation allows a company to take these deductions more quickly — sometimes far more quickly — than the equipment actually wears out. The deductions for the cost of the capital purchase are thus taken earlier, which makes them bigger and more valuable. Accelerated depreciation was first introduced in the 1950s, and then greatly expanded in the 1970s and 1980s. The rules were so generous that many large corporations were able to avoid taxes entirely. This resulted in a public outcry that led to the Tax Reform Act of 1986, which curtailed, but did not eliminate, special tax breaks for capital purchases.

Combined with rules allowing corporations to deduct interest expenses, accelerated depreciation can result in a very low, or even negative, tax rate on profits from particular investments. A corporation can borrow money to purchase equipment or a building, deduct the interest expenses on the debt and quickly deduct the cost of the equipment or building thanks to accelerated depreciation. The total deductions can then be more than the profits generated by the investment.

A report from the Congressional Research Service reviews efforts to quantify the impact of depreciation breaks and explains that “the studies concluded that accelerated depreciation in general is a relatively ineffective tool for stimulating the economy.”[25]

One might argue that some depreciation breaks are more effective than others. For example, the breaks studied most closely by CRS are temporary increases in depreciation breaks (“bonus depreciation”) because these temporary provisions make possible before-and-after comparisons. But CRS analysts have also concluded that the permanent depreciation breaks likely have even less of an impact on economic growth because there is no requirement that they be used before any particular deadline.[26]

Nonetheless, many members of Congress and even many tax analysts seem committed to the (false) idea that depreciation breaks are necessary to spur domestic investment.

Repealing accelerated depreciation would raise a total of $714 billion over a decade, but a portion of that would be a temporary revenue boost reflecting a shift in timing of tax payments. A recent report from the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities explains that revenue raised from repealing accelerated depreciation would be much larger in the first decade than in later decades because part of the revenue increase represents a change in timing of tax payments. (Ending accelerated depreciation would mean that businesses must write off the costs of equipment over the period of time it actually wears out, which is typically longer, meaning they must wait longer to take deductions for these investments.) [27] That report explains that ending accelerated depreciation would raise only about 60 percent as much in later decades as it would raise in the first decade after enactment. We therefore count only 60 percent of the revenue raised in the first decade from ending accelerated depreciation as permanent revenue.

If lawmakers wanted to take a more limited approach than repealing accelerated depreciation altogether, they could opt to curb the worst abuses by barring it for leveraged investments. This would end situations in which the combination of depreciation breaks and interest deductions provide a negative effective tax rate for a given investment. A strong corporate AMT, which was enacted as part of the Tax Reform Act of 1986 but rendered toothless during the 1990s, would also have the effect of limiting the most egregious uses of depreciation breaks.

Repeal deduction for domestic manufacturing

10-year revenue gain: $145 billion[28]

In 2002, the World Trade Organization (WTO) found that a U.S. tax break meant to encourage exports violated U.S. trade treaties with other countries. In the wake of this ruling, the European Union began imposing retaliatory sanctions against the United States in March of 2004. Congressional tax writers immediately moved to comply with the WTO ruling by repealing the illegal tax break. But lawmakers were wary of being seen as hiking taxes on manufacturers — even when the “tax hike” in question resulted from repealing an illegal tax break — and sought to enact new tax cuts that would offset the lost illegal subsidy for manufacturers. However, as the tax bill took shape, this provision was hijacked by legislators seeking to use the tax bill to provide new tax breaks for other favored corporations.

As finally enacted, the “manufacturing deduction” ballooned to apply to a wide variety of corporate activities that no ordinary person would recognize as “manufacturing,” the most egregious of which is oil drilling. The President has proposed to prohibit oil and gas companies from using the break, but Congress should go much farther and repeal the manufacturing deduction altogether. It provides no identifiable benefit to the economy and repealing it altogether could raise $145 billion over a decade.[29]

Reduce the “Mark Zuckerberg loophole” for stock options

10-year revenue gain: $23 billion[30]

For several years, Senator Carl Levin has championed legislation to limit corporate tax deductions for stock options given to highly compensated employees to the amount of the stock option expense that companies report to their shareholders.

Stock options are rights to buy stock at a set price. Corporations sometimes compensate employees (particularly top executives) with these options. The employee can wait to exercise the option until the value of the stock has increased beyond that price, thus enjoying a substantial benefit.

Tax deductions for stock options were very controversial during the years when book rules (accounting rules regarding how companies report expenses to shareholders) conflicted entirely with tax rules (regarding how such expenses are deducted from a company’s income when calculating corporate income taxes). Book rules did not require companies to count stock options as an expense while tax rules did allow companies to count them as an expense to be deducted from their taxable income. Of course, corporations like to report the largest possible profits to shareholders and the lowest possible profits to the IRS for tax purposes, so this situation suited corporate executives.

In other words, corporations were allowed to tell their shareholders one thing and then tell the IRS something different about how stock options affected their profits. Congress made book rules and tax rules less divergent in 2006, but they still differ. Congress changed book rules so that corporations report an expense for stock options both to shareholders and to the IRS, but book write-offs often are still far less than tax write-offs.

Barring corporations from counting stock options as an expense for either book or tax purposes would make more sense. There is no cost to a corporation when it grants stock options, so there is no need for a deduction from taxable income. Corporations compensating employees with stock options are like airlines that compensate employees with free rides on flights that are not full. In both cases the employee receives a form of compensation, and in neither case does it cost the employer anything.[31] No deduction is allowed for the free flights, so none should be allowed for stock options.

Facebook announced in 2012 that it would take $7.5 billion in tax deductions for stock options paid to favored employees, mostly to co-founder Mark Zuckerberg. [32] The following year, Facebook confirmed what was already obvious, that these tax deductions wiped out its tax liability for 2012 and resulted in excess deductions that could be carried back against previous years’ taxes. Despite earning profits of $1 billion in the U.S. in 2012, the company actually received a refund of $429 million.[33] Facebook incurred no real cost but nonetheless wiped out its tax liability, probably for years.

A more modest reform would be to make the book write-offs for stock options identical to what corporations take as tax deductions. Currently, the oddly-designed book rules require the value of the stock options to be guessed at when the options are issued, while the tax deductions reflect the actual value when the options are exercised. Given the uncertainty of what the options will be worth when exercised and the fact that corporations have an incentive to guess on the low side (so they can report higher profits to shareholders), it’s no wonder that their guesses are always wrong, and typically too low.

The legislation introduced by Senator Levin would not bar companies from counting stock options as an expense for book or tax purposes. It would, however, bar companies from taking tax deductions for stock options that are larger than the expenses they booked for shareholder-reporting purposes. It would also remove the loophole that exempts compensation paid in stock options from the existing rule capping companies’ deductions for compensation at $1 million per executive.

Eliminate fossil fuel tax preferences

10-year revenue gain: $51 billion[34]

There are several tax breaks that subsidize the extraction and sale of oil, natural gas and coal, which President Obama has proposed to eliminate. Repealing these breaks can be justified as a way to help the environment by redirecting resources away from dirty fuels, and also simply because it does not make economic sense for the government to give tax subsidies to an industry that is already extremely profitable. Most of the revenue raised from ending tax breaks for fossil fuels would come from three proposals.

One of these proposals would repeal the deduction for “intangible” costs of exploring and developing oil and gas sources. The “intangible” costs of exploration and development generally include wages, costs of using machinery for drilling and the costs of materials that get used up during the process of building wells. Most businesses must write off such expenses over the useful life of the property, but oil companies, thanks to their lobbying clout, get to write these expenses off immediately.

Another proposal would repeal “percentage depletion” for oil and gas properties. Most businesses must write off the actual costs of their property over its useful life (until it wears out). If oil companies had to do the same, they would write off the cost of oil fields until the oil was depleted. Instead, some oil companies get to simply deduct a flat percentage of gross revenues. The percentage depletion deductions can actually exceed costs and can zero out all federal taxes for oil and gas companies. The Energy Policy Act of 2005 actually expanded this provision to allow more companies to enjoy it.

The President also proposes to bar oil and gas companies from using the manufacturing tax deduction. The manufacturing tax deduction was added to the law in 2004 and allows companies to deduct 9 percent of their net income from domestic production. Some might wonder why oil and gas companies can use a deduction for “manufacturing” in the first place. But Congress specifically included “extraction” in the definition of manufacturing so that it included oil and gas production, obviously at the behest of the industry.

Reform like-kind exchange rules

10-year revenue gain: $11 billion[35]

Another reform proposed by President Obama would limit the taxes that can be deferred under existing rules for profits from “like-kind exchanges” to $1 million. This limit would be indexed to inflation.

Businesses can take tax deductions for depreciation on their properties, and then sell these properties at an appreciated price while avoiding capital gains tax, through what is known as a “like-kind exchange.” The break was originally intended for situations in which two ranchers or two farmers decided to trade some land. Since neither had sold their land for cash and they were still using the land to make a living, it seemed reasonable at the time to waive the rules that would normally define this as a sale and tax any gains from it.

But the break has turned into a multi-billion-loophole that has been widely exploited by many giant companies, including General Electric, Cendant and Wells Fargo.[36] In fact, the “tax expenditure report” of the Joint Committee on Taxation (JCT) shows that most of the revenue lost as a result of this tax expenditure actually goes to corporations, not individuals.[37]

By limiting the tax deferral for like-kind exchanges to $1 million, the President’s proposal ensures that the break is less abused than it is today.

IV. Revenue Options Affecting Multinational Corporations

Repeal “deferral”

10-year revenue gain: 601 billion

(plus $158 billion temporary impact in the first decade)[38]

One of the very largest tax expenditures, one that only benefits corporations, is so-called “deferral.” This is the rule allowing American corporations to “defer” paying U.S. taxes on the profits of their offshore subsidiaries until those profits are officially “repatriated.” That’s another way of saying Americans corporations are allowed to delay paying U.S. taxes on their offshore profits until those offshore profits are officially brought to the U.S. A corporation can go years without paying U.S. taxes on those profits, and may never pay U.S. taxes on those profits.

This creates two terrible incentives for American corporations. First, in some situations it encourages them to shift their operations and jobs to a country with lower taxes. Second, it encourages them to use accounting gimmicks to disguise their U.S. profits as foreign profits generated by a subsidiary company in some other country that has much lower taxes or that doesn’t tax these profits at all.

The countries that have extremely low taxes or no taxes on profits are known as tax havens. And the subsidiary company in the tax haven that is claimed to make all these profits is often nothing more than a post office box.

The corporate income tax has rules that are supposed to limit this practice of artificially shifting profits (on paper) to offshore tax havens. For example, American corporations are not allowed to defer U.S. taxes on “passive income,” which refers to certain types of income that Congress considers too easy to shift around from one country to another. And there are “transfer pricing” rules, which require that a U.S. corporation and its offshore subsidiary (which are really two parts of the same company) deal with each other at “arm’s length” when there is a transaction of some sort between them. In other words, if a U.S. corporation is transferring, say, a patent to its offshore subsidiary, it’s supposed to pretend that the subsidiary is an unrelated company and charge it a fair market price for the patent. And if the subsidiary wants to allow the U.S. corporation to use the patent, it must charge royalties at a fair market price.

These rules are failing to prevent abuses of deferral. The IRS cannot easily identify a fair market price for (for example) a patent for a brand new invention, particularly when there is no similar transaction in the marketplace for the IRS to look to for comparison. American corporations are therefore able to transfer patents to subsidiaries in Bermuda or the Cayman Islands at very low prices and then pay inflated royalties to these subsidiaries for the use of those patents — and then claim to the IRS that they have no U.S. profits as a result.

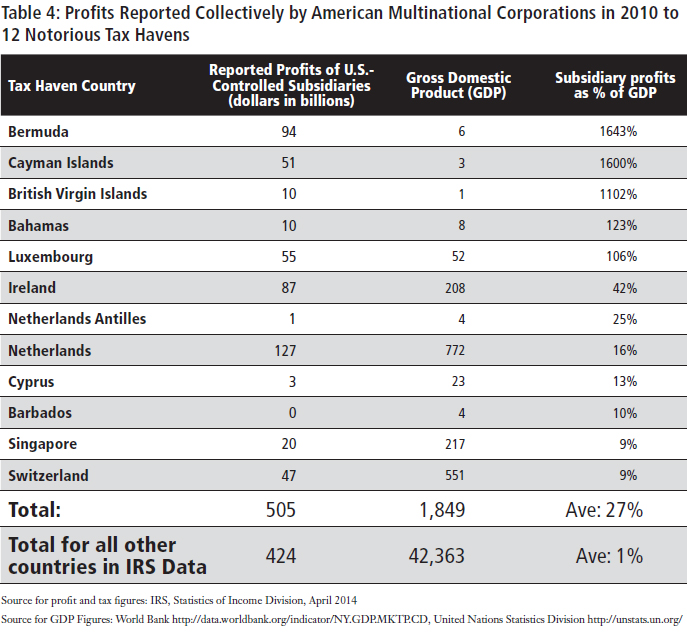

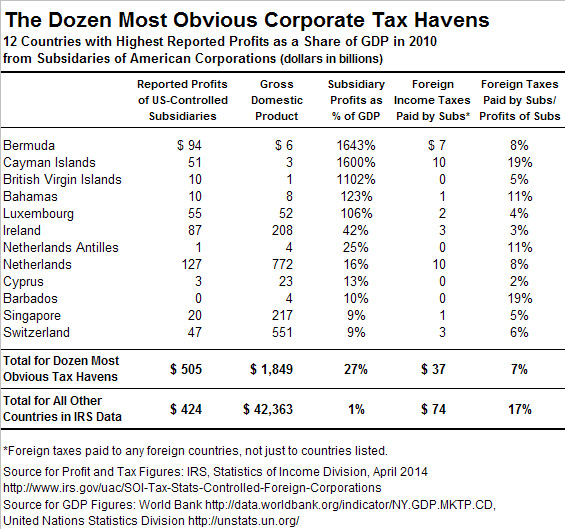

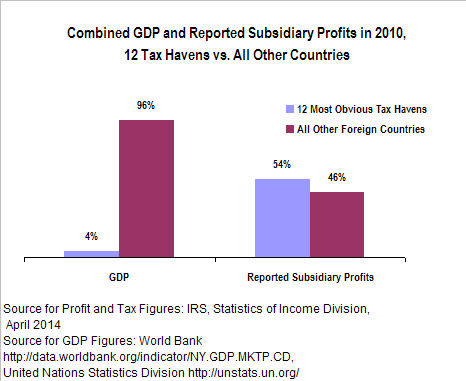

Recent data from the IRS confirm that this sort of corporate tax dodging involving offshore tax havens is happening on a massive scale. For example, the profits that American corporations report to the IRS that they earn through their subsidiaries in Bermuda totaled $94 billion in 2010. But Bermuda’s gross domestic product (GDP) in 2010 was just $6 billion. It is obviously impossible for American corporations to have profits in Bermuda that equal more than 16 times all the goods and services produced in that country. Similarly, American corporations reported to the IRS that their subsidiaries in the Cayman Islands earned $51 billion in 2010 even though that country’s GDP was just $3 billion, and they reported their subsidiaries earned $10 billion in the British Virgin Islands even though that country’s GDP was just $1 billion.[39]

It is clear that most of the profits reported to be earned in these countries were truly earned in the U.S. or other developed countries and manipulated through accounting gimmicks so that they appear to be earned in countries where they will be taxed lightly or not at all.

The most straightforward solution is to repeal deferral. This would mean that all the profits of American corporations are subject to the U.S. corporate income tax whether they are domestic profits or foreign profits generated by offshore subsidiaries. There would be no incentive for an American corporation to move its operations offshore or to make its U.S. profits appear to be generated in an offshore tax haven.

American corporations would continue to receive a credit against their U.S. taxes for corporate taxes paid to any foreign government (the foreign tax credit), just as they do now, to prevent double-taxation. For example, imagine an American corporation has a subsidiary in another country and pays a corporate tax of 20 percent of the profits it earns there to that country’s government. Under the current rules, the American corporation can indefinitely defer paying any U.S. tax on those profits by keeping them in the foreign country. (And characterizing these profits as “offshore” may be largely an accounting matter.) When it does “repatriate” those profits (bring them to the U.S.) it receives a credit for the 20 percent it already paid to the foreign government and then pays the difference between the U.S. corporate income tax rate of 35 percent and the rate of 20 percent paid to the foreign government, which comes to a 15 percent rate paid to the U.S.

If Congress repeals deferral, the American corporation would still receive the foreign tax credit and still only pay 15 percent to the U.S. government. The only difference is that the company would be required to pay that tax the same year the profits are earned regardless of whether or not the profits are brought back to the U.S.

In other words, the total tax due the year the profits are earned would be the same, 35 percent, regardless of whether those profits were generated in the U.S. or in another country. There would therefore be no incentive for an American corporation to make its U.S. profits appear to be generated in an offshore tax haven.

Part of the revenue that would be raised during the first decade after deferral is repealed is really just a timing shift in tax payments. This is because some of the offshore profits for which U.S. taxes are deferred under current law would have eventually been brought to the U.S. and subject to U.S. taxes. But most of the revenue raised comes from U.S. taxes paid on profits that would not have been brought to the U.S. under the current rules and from shifting to a system that no longer provides incentives for corporations to shift profits or operations offshore.

Bar deduction for interest expense for offshore business until profits are taxed

10-year revenue gain: $51 billion[40]

One of President Obama’s proposals to limit the worst abuses of deferral would require that U.S. companies defer deductions for interest expenses related to earning income abroad until that income is subject to U.S. taxation (if ever).

U.S. multinational companies are allowed to “defer” U.S. taxes on income generated by their foreign subsidiaries until that income is officially brought to the U.S. (“repatriated”). There are numerous problems with deferral, but it’s particularly problematic when a U.S. company defers U.S. taxes on foreign income for years even while it deducts the expenses of earning that foreign income immediately to reduce its U.S. taxable profits. For example, an American corporation could borrow to buy stock in a foreign corporation and deduct the interest payments on that debt immediately even if it defers for years paying U.S. taxes on the profits from the investment in the foreign company. In this situation, the tax code effectively subsidizes American corporations for investing offshore rather than in the U.S.

Under the President’s proposal, the share of interest payments on debt used to invest abroad that could be deducted would be limited to the share of income from those offshore investments that is subject to U.S. taxes in a given year. The rest of the deductions for interest payments would be deferred, just as U.S. taxes on the rest of the offshore profits are deferred.

The version of this proposal included in the President’s first budget was stronger because it would have required that U.S. companies defer deductions for all expenses (other than research and experimentation expenses) relating to earning income abroad until that income is subject to U.S. taxation. The current proposal only applies to interest expenses.

Calculate foreign tax credits on a “pooling” basis

10-year revenue gain: $59 billion[41]

This proposal, which is also included in the President’s budget, would require that the foreign tax credit be calculated on a consolidated basis, or “pooling basis,” in order to prevent corporations from taking the credit in excess of what is necessary to avoid double-taxation on their foreign profits.

The foreign tax credit allows American corporations to subtract whatever corporate income taxes they have paid to foreign governments from their U.S. tax bill. This makes sense in theory, because it prevents the offshore profits of American corporations from being double-taxed.

But, unfortunately, corporations sometimes get foreign tax credits that exceed the U.S. taxes that apply to such income, meaning that the U.S. corporations are using foreign tax credits to reduce their U.S. taxes on their U.S. profits, not just avoiding double taxation on their foreign income.

For example, say a U.S. corporation owns two foreign subsidiaries, one in a country where it actually does business and pays taxes, the other in a tax haven where it does no real business and pays no taxes. The U.S. corporation has accumulated profits in both foreign subsidiaries. If the U.S. company decides to officially bring some of its foreign profits back to the U.S., it can say that the profits it has “repatriated” all came from the taxable foreign corporation, thereby maximizing its foreign tax credit that it can use to reduce its U.S. tax on the repatriation.

Under the President’s proposal, the U.S. corporation would be required to compute the foreign tax credit as if the dividend was paid proportionately from each of its foreign subsidiaries. Since no foreign tax was paid on the profits in the tax haven, this approach will reduce the U.S. company’s foreign tax credit to the correct amount.

Restrict excessive interest deductions used for earnings stripping

10-year revenue gain: $41 billion[42]

The President also proposes a reform to restrict “earnings stripping,” the practice of multinational corporations earning profits in the United States reducing or eliminating their U.S. profits for tax purposes by making large interest payments to their foreign affiliates.

The President would allow a multinational corporation doing business in the U.S. to take deductions for interest payments to its foreign affiliates only to the extent that the U.S. entity’s share of the interest expenses of the entire corporate group (the entire group of corporations owned by the same parent corporation) is proportionate to its share of the corporate group’s earnings (calculated by adding back interest expenses and certain other deductible expenses). The corporation doing business in the U.S. could also choose instead to be subject to a different rule, limiting deductions for interest payment to ten percent of “adjusted taxable income” (which is taxable income plus several amounts that are usually deducted for tax purposes).

Most of the President’s international tax reform proposals address situations in which American corporations attempt to claim that their U.S. profits are actually earned by their affiliated corporations in other countries. This proposal is different in that it also addresses situations in which the American corporation is itself a subsidiary of a foreign corporation (at least on paper, since the foreign corporation can actually be a shell corporation in a tax haven).

In this situation, the American company is subject to U.S. corporate income taxes, but “earnings stripping” is used to make the American profits appear to be earned by the foreign corporation and thus not taxable in the U.S. To accomplish this, the U.S. company is loaded up with debt that is owed to the affiliated foreign company. The U.S. company then makes large interest payments (which reduce or wipe out its taxable income) to the foreign company.

Section 163(j) of the tax code was enacted in 1989 to prevent this practice, but it seems to be failing. It bars corporations from taking deductions for interest payments if their debt is more than one and a half times their equity (capital invested by stockholders) and the interest exceeds 50 percent of the company’s “adjusted taxable income” (taxable income plus several amounts that are usually deducted for tax purposes).

The problem is that an American corporation could have debt and interest payments that are below these thresholds but still high relative to the rest of the corporate group (the rest of the corporations all ultimately owned by the same parent corporation). For example, imagine a foreign corporation owns five subsidiary corporations, one in the U.S. and the other four in countries with much lower tax rates or no corporate income tax at all. If the American corporation tells the IRS that it generated a fifth of the revenue of the corporate group but also has half of the interest expense of the entire group, the IRS ought to be able to surmise that this has been arranged to artificially reduce U.S. profits to avoid U.S. taxes — even if the thresholds for the existing section 163(j) have not been breached. This is one of the problems that the President’s proposal would address.

Prevent American corporations from “inverting” (becoming foreign corporations for tax purposes)

10-year revenue gain: $19.5 billion[43]

A proposal in Congress would prevent American corporations from pretending to be “foreign” companies to avoid taxes even while they maintain most of their ownership, operations and management in the United States. This proposal is a slightly stronger version of a reform first proposed by President Obama in his budget plan.

The Stop Corporate Inversions Act requires the entity resulting from a U.S.-foreign merger to be treated as a U.S. corporation for tax purposes if it is majority owned by shareholders of the acquiring American company or if it is managed in the U.S. and has substantial business here. These are common sense rules and many people might be surprised to learn that they are not already part of our tax laws. In fact, the law on the books now (a law enacted in 2004) recognizes the inversion unless the merged company is more than 80 percent owned by the shareholders of the acquiring American corporation and does not have substantial business in the country where it is incorporated.

The current law therefore does prevent corporations from simply signing some papers and declaring itself to be reincorporated in, say, Bermuda. But it doesn’t address the situations in which an American corporation tries to add a dollop of legitimacy to the deal by obtaining a foreign company that is doing actual business in another country.

The management of Pfizer recently attempted to acquire the British drug maker AstraZeneca for this purpose.[44] A group of hedge funds that own stock in the drug store chain Walgreen have been pushing that company to increase its stake in the European company Alliance Boots for the same purpose.[45]

[1] During the most recent year for which OECD data are available, the United States collected lower taxes as a share of GDP than all but two OECD countries, Chile and Mexico. See Citizens for Tax Justice, “The U.S. Is One of the Least Taxed of the Developed Countries,” April 7, 2014. http://ctj.org/ctjreports/2014/04/the_us_is_one_of_the_least_taxed_of_the_developed_countries.php

[2] The figures presented in the following paragraph and nearby graph first appeared in Citizens for Tax Justice, “Who Pays Taxes in America in 2014?,” April 7, 2014. http://ctj.org/ctjreports/2014/04/who_pays_taxes_in_america_in_2014.php

[3] Citizens for Tax Justice and the Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, “The Sorry State of Corporate Taxes,” February 26, 2014. http://www.ctj.org/corporatetaxdodgers/

[4] Julie-Anne Cronin, Emily Y. Lin, Laura Power, and Michael Cooper, “Distributing the Corporate Income Tax: Revised U.S. Treasury Methodology,” Treasury Department, 2012. http://www.treasury.gov/resource-center/tax-policy/tax-analysis/Documents/OTA-T2012-05-Distributing-the-Corporate-Income-Tax-Methodology-May-2012.pdf

[5] Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy (ITEP) microsimulation tax model, June, 2014. As explained in the main text, an official revenue estimate for this proposal from the Joint Committee on Taxation (JCT) would likely be quite different because JCT makes different assumptions about behavioral impacts. Our analysis adopts assumptions regarding behavioral impacts that have been argued to be more realistic by the Congressional Research Service.

[6] Warren E. Buffett, “Stop Coddling the Super-Rich,” New York Times op-ed, August 14, 2011. http://www.nytimes.com/2011/08/15/opinion/stop-coddling-the-super-rich.html?_r=1&scp=1

[7] These claims are easily refuted. Revenue collected from taxing capital gains was greater during the Clinton years when the rate was higher than in years after 2003 when the rate was reduced under President Bush. See Citizens for Tax Justice, “Ending the Capital Gains Tax Preference would Improve Fairness, Raise Revenue and Simplify the Tax Code,” September 20, 2012. http://ctj.org/ctjreports/2012/09/ending_the_capital_gains_tax_preference_would_improve_fairness_raise_revenue_and_simplify_the_tax_co.php Also, claims that the 1986 tax reform caused a drop-off in capital gains tax revenue fail to mention that there was an increase in capital gains tax revenue leading up to the reform going into effect, as individuals rushed to cash in assets before their tax preferences disappeared, and then afterwards such sales naturally dropped off from this artificial high point.

[8] CBO and JCT have not examined the option of totally eliminating the income tax preference for capital gains but have analyzed a very small reduction in the preference. Congressional Budget Office, “Options for Reducing the Deficit: 2014 to 2023,” November 2013, p. 111. http://www.cbo.gov/budget-options/2013/44687 The option studied by CBO would raise the capital gains rates by 2 percentage points and raise $53.4 billion from 2014 through 2023.

[9] Jane Gravelle, “Capital Gains Tax Options: Behavioral Responses and Revenue,” Congressional Research Service, August 10, 2010.

[10] Citizens for Tax Justice, “Policy Options to Raise Revenue,” March 9, 2012. http://ctj.org/ctjreports/2012/03/policy_options_to_raise_revenue.php

[11] Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy (ITEP) microsimulation tax model, June, 2014.

[12] Citizens for Tax Justice, “Fact Sheet: Why We Need the Corporate Income Tax,” June 10, 2013. http://ctj.org/ctjreports/2013/06/fact_sheet_why_we_need_the_corporate_income_tax.php

[13] Joint Committee on Taxation, “Estimated Budget Effects of the Revenue Provisions Contained in the President’s Fiscal Year 2015 Budget Proposal,” JCX-36-14, April 15, 2014. https://www.jct.gov/publications.html?func=startdown&id=4585

[14] Joint Committee on Taxation, “Estimated Budget Effects of the Revenue Provisions Contained in the President’s Fiscal Year 2015 Budget Proposal,” JCX-36-14, April 15, 2014. https://www.jct.gov/publications.html?func=startdown&id=4585

[15] Citizens for Tax Justice, “How to Implement the Buffett Rule,” October 19, 2011. http://ctj.org/ctjreports/2011/10/how_to_implement_the_buffett_rule.php

[16] Joint Committee on Taxation, “Estimated Budget Effects of the Revenue Provisions Contained in the President’s Fiscal Year 2015 Budget Proposal,” JCX-36-14, April 15, 2014. https://www.jct.gov/publications.html?func=startdown&id=4585

[17] Fund managers can invest their own money in the funds, but of course, tax treatment of any return on investments made with their own money would not be affected by the repeal of the carried interest loophole. (Profits from investments actually made by the managers themselves could still be taxed as capital gains).

[18] Joint Committee on Taxation, “Estimated Budget Effects of the Revenue Provisions Contained in the President’s Fiscal Year 2010 Budget Proposal,” JCX-36-14, June 11, 2009. https://www.jct.gov/publications.html?func=startdown&id=3618

[19] Department of the Treasury, “General Explanations of the Administration’s Fiscal Year 2015 Revenue Proposals,” March 2014, p. 177. http://www.treasury.gov/resource-center/tax-policy/Documents/General-Explanations-FY2015.pdf

[20] Citizens for Tax Justice, “Payroll Tax Loophole Used by John Edwards and Newt Gingrich Remains Unaddressed by Congress,” September 6, 2013. http://www.ctj.org/taxjusticedigest/archive/2013/09/payroll_tax_loophole_used_by_j.php

[21] Joint Committee on Taxation, “Estimated Budget Effects of the Revenue Provisions Contained in the President’s Fiscal Year 2015 Budget Proposal,” JCX-36-14, April 15, 2014. https://www.jct.gov/publications.html?func=startdown&id=4585

[22] Citizens for Tax Justice, “Working Paper on Tax Reform Options,” revised February 4, 2013. http://ctj.org/ctjreports/2013/02/working_paper_on_tax_reform_options.php

[23] Department of the Treasury, “General Explanations of the Administration’s Fiscal Year 2015 Revenue Proposals,” March 2014. http://www.treasury.gov/resource-center/tax-policy/Documents/General-Explanations-FY2015.pdf

[24] This estimate is based on the estimates provided by the Joint Committee on Taxation (JCT) of the impacts of Senator Ron Wyden’s Bipartisan Tax Fairness and Simplification Act of 2010, which includes repeal of accelerated depreciation. Joint Committee on Taxation, “Estimated Revenue Effects of S. 3018, the “Bipartisan Tax Fairness and Simplification Act of 2010,” November 2, 2010. http://www.wyden.senate.gov/download/joint-committee-on-taxation-estimated-score-of-the-bipartisan-tax-fairness-and-simplification-act-of-2010 JCT’s estimates separate the impacts of eliminating business tax expenditures, reducing the corporate income tax rate, and the interaction between the two. This allows us to calculate the revenue impact of enacting these provisions without a reduction in the corporate tax rate. We adjust the revenue estimates for each year based on more recent CBO revenue estimates to account for the later time period we examine (2015 through 2024) and to account for the greater corporate profits that JCT now predicts during the coming decade. We then draw on other research that suggests only about 60 percent of the revenue impact from ending accelerated depreciation would be a permanent impact sustained in the following decades. Chye-Ching Huang, Chuck Marr, and Nathaniel Frentz, “Timing Gimmicks Pose Threat to Fiscally Responsible Tax Reform,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, July 24, 2013. http://www.cbpp.org/cms/index.cfm?fa=view&id=3994

[25] Gary Guenther, “Section 179 and Bonus Depreciation Expensing Allowances: Current Law, Legislative Proposals in the 112th Congress, and Economic Effects,” Congressional Research Service, September 10, 2012. http://www.fas.org/sgp/crs/misc/RL31852.pdf

[26] Statement of Jane G. Gravelle, Senior Specialist in Economic Policy, Congressional Research Service, before the Committee on Finance, United States Senate, March 6, 2012, on Tax Reform Options: Incentives for Capital Investment and Manufacturing, pages 5-6. http://www.finance.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/Testimony%20of%20Jane%20Gravelle.pdf

[27] Chye-Ching Huang, Chuck Marr, and Nathaniel Frentz, “Timing Gimmicks Pose Threat to Fiscally Responsible Tax Reform,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, July 24, 2013. http://www.cbpp.org/cms/index.cfm?fa=view&id=3994

[28] The estimate is based on the revenue estimate provided by the Joint Committee on Taxation for the Rep. Dave Camp’s tax reform plan, which includes a proposal to repeal the domestic manufacturing deduction. The estimate is adjusted to reflect that this proposal would go into effect in 2015, whereas Rep. Camp’s plan would not fully repeal the deduction until 2017. Joint Committee on Taxation, Estimated Revenue Effects of the Tax Reform Act of 2014, February 26, 2014, JCX-20-14. http://waysandmeans.house.gov/uploadedfiles/jct_revenue_estimate__jcx_20_14__022614.pdf

[29] Repeal of the manufacturing deduction would also greatly help many state governments. This is because many states have corporate income taxes that are linked to the federal corporate income tax, so a deduction on the federal level applies on the state level as well. State lawmakers can enact legislation to “decouple” from the federal rules related to this deduction. But political and constitutional constraints in some states make it difficult to enact any sort of “tax increase,” even when it only consists of decoupling from federal rules allowing a deduction. See Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, “The QPAI Corporate Tax Break: How It Works and How States Can Respond,” October 2008. http://www.itepnet.org/pb33qpai.pdf

[30] Statement of Senators Levin and McCain on Stock Option Tax Deductions, November 6, 2013. http://www.levin.senate.gov/newsroom/press/release/statement-of-senators-levin-and-mccain-on_stock-option-tax-deductions

[31] In theory, there could be some cost to existing shareholders when individuals are allowed to buy stock for less than it’s worth, but the same is true whenever a corporation issues new stock and this does not generate a tax deduction for the corporation.

[32] For a more detailed explanation, see Citizens for Tax Justice, “Putting a Face(book) on the Corporate Stock Option Tax Loophole,” February 7, 2012. https://ctj.sfo2.digitaloceanspaces.com/pdf/FacebookReport.pdf

[33] Citizens for Tax Justice, “Facebook’s Multi-Billion Dollar Tax Break: Executive-Pay Tax Break Slashes Income Taxes on Facebook — and Other Fortune 500 Companies,” February 14, 2013. http://ctj.org/ctjreports/2013/02/facebooks_multi-billion_dollar_tax_break_executive-pay_tax_break_slashes_income_taxes_on_facebook–.php

[34] Joint Committee on Taxation, “Estimated Budget Effects of the Revenue Provisions Contained in the President’s Fiscal Year 2015 Budget Proposal,” JCX-36-14, April 15, 2014. https://www.jct.gov/publications.html?func=startdown&id=4585

[35] Joint Committee on Taxation, “Estimated Budget Effects of the Revenue Provisions Contained in the President’s Fiscal Year 2015 Budget Proposal,” JCX-36-14, April 15, 2014. https://www.jct.gov/publications.html?func=startdown&id=4585

[36] David Kocieniewski, “Major Companies Push the Limits of a Tax Break,” The New York Times, January 6, 2013. http://www.nytimes.com/2013/01/07/business/economy/companies-exploit-tax-break-for-asset-exchanges-trial-evidence-shows.html?pagewanted=all&_r=0

[37] Joint Committee on Taxation, “Estimates Of Federal Tax Expenditures For Fiscal Years 2012-2017,” JCS-1-13, February 01, 2013. https://www.jct.gov/publications.html?func=startdown&id=4503

[38] This estimate is based on the estimates provided by the Joint Committee on Taxation (JCT) of the impacts of Senator Ron Wyden’s 2010 tax reform plan, which includes repeal of deferral. See Joint Committee on Taxation, “Estimated Revenue Effects of S. 3018, the Bipartisan Tax Fairness and Simplification Act of 2010,” November 2, 2010. http://www.wyden.senate.gov/download/joint-committee-on-taxation-estimated-score-of-the-bipartisan-tax-fairness-and-simplification-act-of-2010 JCT’s estimates separate the impacts of eliminating business tax expenditures, reducing the corporate income tax rate, and the interaction between the two. This allows us to calculate the revenue impact of enacting these provisions without a reduction in the corporate tax rate. We adjust the revenue estimates for each year based on more recent CBO revenue estimates to account for the later time period we examine (2015 through 2024) and to account for the greater corporate profits that JCT now predicts during the coming decade.

[39] Citizens for Tax Justice, “American Corporations Tell IRS the Majority of Their Offshore Profits Are in 12 Tax Havens,” May 27, 2014. http://ctj.org/ctjreports/2014/05/american_corporations_tell_irs_the_majority_of_their_offshore_profits_are_in_12_tax_havens.php

[40] Joint Committee on Taxation, “Estimated Budget Effects of the Revenue Provisions Contained in the President’s Fiscal Year 2015 Budget Proposal,” JCX-36-14, April 15, 2014. https://www.jct.gov/publications.html?func=startdown&id=4585

[41] Joint Committee on Taxation, “Estimated Budget Effects of the Revenue Provisions Contained in the President’s Fiscal Year 2015 Budget Proposal,” JCX-36-14, April 15, 2014. https://www.jct.gov/publications.html?func=startdown&id=4585

[42] Joint Committee on Taxation, “Estimated Budget Effects of the Revenue Provisions Contained in the President’s Fiscal Year 2015 Budget Proposal,” JCX-36-14, April 15, 2014. https://www.jct.gov/publications.html?func=startdown&id=4585

[43] Letter from Joint Committee on Taxation to Karen McAfee, Ways and Means Committee Democratic staff, May 23, 2014. http://democrats.waysandmeans.house.gov/sites/democrats.waysandmeans.house.gov/files/113-0927%20JCT%20Revenue%20Estimate.pdf

[44] Citizens for Tax Justice, “Why Does Pfizer Want to Renounce Its Citizenship?” April 30, 2014. http://www.taxjusticeblog.org/archive/2014/04/pfizer_is_a_bad_corporate_citi.php

[45] Citizens for Tax Justice, “Walgreens May Become a ‘Foreign’ Company to Avoid Taxes — But an Obama Proposal Could Stop Them,” April 24, 2014. http://www.ctj.org/taxjusticedigest/archive/2014/04/walgreens_may_become_a_foreign.php

![]()

“Reports are stating that Walgreen Co. has decided to set aside — for now — plans to avoid U.S. taxes by reincorporating as a foreign company. Only the proverbial fly on the boardroom wall truly knows what led the company to reach this decision. But a single company backing off plans to exploit loopholes in our tax code to dodge U.S. taxes does not fix the fundamental problem.

“Reports are stating that Walgreen Co. has decided to set aside — for now — plans to avoid U.S. taxes by reincorporating as a foreign company. Only the proverbial fly on the boardroom wall truly knows what led the company to reach this decision. But a single company backing off plans to exploit loopholes in our tax code to dodge U.S. taxes does not fix the fundamental problem.

Now consider a receptionist who works at the brokerage firm that handles some of the heiress’s dealings. Let’s say this receptionist earns $50,000 a year. Unlike the heiress, his income comes in the form of wages, because, alas, he has to work for a living. His wages are taxed at progressive income tax rates, and a portion of his income is actually taxed at 25 percent. (In other words, he faces a marginal income tax rate of 25 percent, meaning each additional dollar he earns is taxed at that amount).

Now consider a receptionist who works at the brokerage firm that handles some of the heiress’s dealings. Let’s say this receptionist earns $50,000 a year. Unlike the heiress, his income comes in the form of wages, because, alas, he has to work for a living. His wages are taxed at progressive income tax rates, and a portion of his income is actually taxed at 25 percent. (In other words, he faces a marginal income tax rate of 25 percent, meaning each additional dollar he earns is taxed at that amount). The unfairness of the dividends tax preference is straightforward. The wealthy heiress in the example above who lives off her wealth would likely receive income in the form of stock dividends just as she receives income in the form of capital gains, and in both cases she is taxed much less than someone who works to earn the same (or a much lower) amount of income.

The unfairness of the dividends tax preference is straightforward. The wealthy heiress in the example above who lives off her wealth would likely receive income in the form of stock dividends just as she receives income in the form of capital gains, and in both cases she is taxed much less than someone who works to earn the same (or a much lower) amount of income. This is an odd way to subsidize activities that Congress favors. If Congress provided such subsidies through direct spending, there would likely be a public outcry over the fact that rich people are subsidized at higher rates than low- and middle-income people. But because these subsidies are provided through the tax code, this fact has largely escaped the public’s attention.

This is an odd way to subsidize activities that Congress favors. If Congress provided such subsidies through direct spending, there would likely be a public outcry over the fact that rich people are subsidized at higher rates than low- and middle-income people. But because these subsidies are provided through the tax code, this fact has largely escaped the public’s attention.

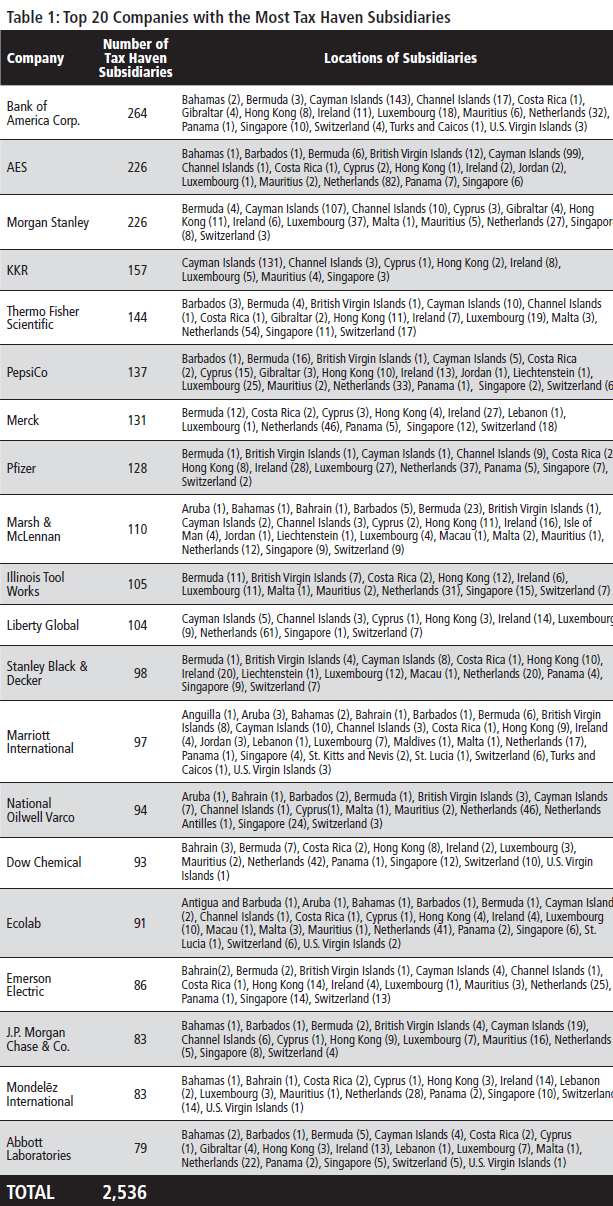

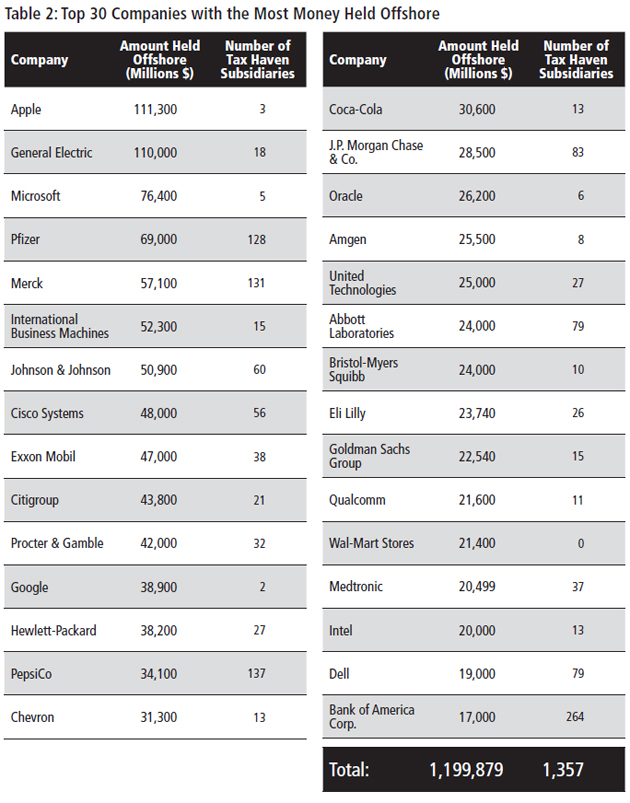

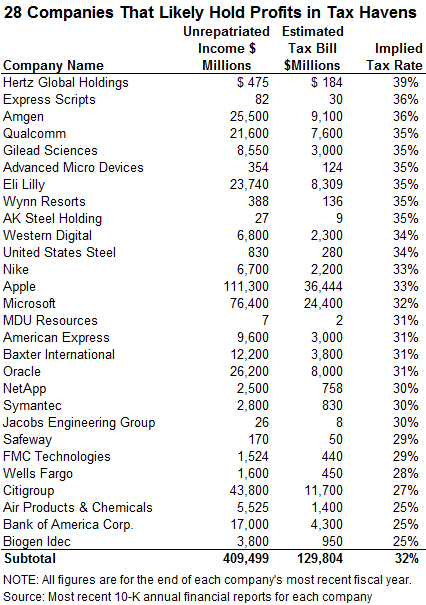

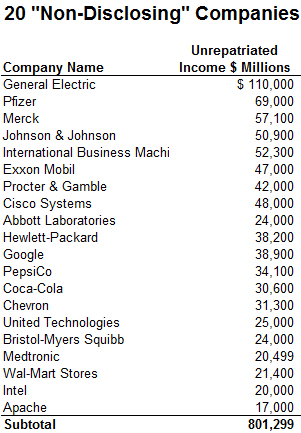

While hundreds of companies refuse to disclose the tax they likely owe on their offshore cash, just a handful of these companies account for the lion’s share of the permanently reinvested foreign profits in the Fortune 500. The nearby table shows the 20 non-disclosing companies with the biggest offshore stash at the end of the most recent fiscal year. These 20 companies held $801 billion in unrepatriated offshore income — more than half of the total income held by the 243 “non-disclosing” companies. Most of these companies also disclose, elsewhere in their financial reports, owning subsidiaries in known tax havens. For example:

While hundreds of companies refuse to disclose the tax they likely owe on their offshore cash, just a handful of these companies account for the lion’s share of the permanently reinvested foreign profits in the Fortune 500. The nearby table shows the 20 non-disclosing companies with the biggest offshore stash at the end of the most recent fiscal year. These 20 companies held $801 billion in unrepatriated offshore income — more than half of the total income held by the 243 “non-disclosing” companies. Most of these companies also disclose, elsewhere in their financial reports, owning subsidiaries in known tax havens. For example: