March 13, 2013 02:40 PM | Permalink | ![]()

House Budget Chairman Paul Ryan’s budget plan for fiscal year 2014 and beyond includes a specific package of tax cuts (including reducing income tax rates to 25 percent and 10 percent) and no details on how Congress would offset their costs, all the while proposing to maintain the level of revenue that will be collected by the federal government under current law.

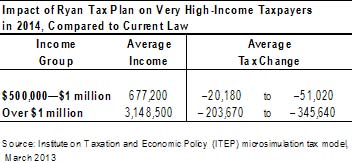

The revenue loss would  presumably be offset by reducing or eliminating tax expenditures (tax breaks targeted to certain activities or groups), as in his previous budget plans. For taxpayers with income exceeding $1 million, the benefit of Ryan’s tax rate reductions and other proposed tax cuts would far exceed the loss of any tax expenditures. In fact, under Ryan’s plan taxpayers with income exceeding $1 million in 2014 would receive an average net tax decrease of over $200,000 that year even if they had to give up all of their tax expenditures. These taxpayers would see an even larger net tax decrease if Congress failed to limit or eliminate enough tax expenditures to offset the costs of the proposed tax cuts.

presumably be offset by reducing or eliminating tax expenditures (tax breaks targeted to certain activities or groups), as in his previous budget plans. For taxpayers with income exceeding $1 million, the benefit of Ryan’s tax rate reductions and other proposed tax cuts would far exceed the loss of any tax expenditures. In fact, under Ryan’s plan taxpayers with income exceeding $1 million in 2014 would receive an average net tax decrease of over $200,000 that year even if they had to give up all of their tax expenditures. These taxpayers would see an even larger net tax decrease if Congress failed to limit or eliminate enough tax expenditures to offset the costs of the proposed tax cuts.

Given that Ryan’s plan specifies how taxes would be cut, but not how tax expenditures would be reduced to offset the costs, it is nearly impossible to estimate the impacts on taxpayers in most income groups. However, for very high-income taxpayers, it is possible to estimate a range of impacts, with one extreme being a scenario in which these taxpayers must give up all tax expenditures, and the other extreme being a scenario in which they give up no tax expenditures.[1]

The table above illustrates these two possible scenarios by including estimates of the minimum and maximum average net tax cuts that high-income taxpayers could receive in 2014 under Chairman Ryan’s plan. Because these very high-income taxpayers would pay less than they do today in either scenario, the average net impact of Ryan’s plan on some taxpayers at lower income levels would necessarily be a tax increase in order to fulfill Ryan’s goal of collecting the same amount of revenue as expected under current law.

The estimates of the minimum average net tax cuts assume that wealthy taxpayers would have to give up all of the tax expenditures that benefit them directly — except the huge breaks for investing and saving, which Ryan has pledged in the past to leave in place.[2] These tax breaks for investing and saving, particularly the lower tax rates for capital gains and stock dividends, provide the greatest benefits to the richest taxpayers. The estimates of the minimum average tax cuts also assume that the reduction in the corporate income tax rate would be offset by the elimination or reduction in tax expenditures that benefit businesses.

The estimates of the maximum average net tax cuts, on the other hand, assume that no tax expenditures are eliminated or reduced. The maximum average net tax breaks are what high-income taxpayers would receive if Congress enacts the specific tax cuts proposed in Ryan’s plan with no provisions to offset the revenue loss by limiting tax expenditures.

Chairman Ryan’s budget plan lays out (on page 24) the following “solutions” for our tax system:

• Simplify the tax code to make it fairer to American families and businesses.

• Reduce the amount of time and resources necessary to comply with tax laws.

• Substantially lower tax rates for individuals, with a goal of achieving a top individual rate of 25 percent.

• Consolidate the current seven individual-income-tax brackets into two brackets with a first bracket of 10 percent.

• Repeal the Alternative Minimum Tax.

• Reduce the corporate tax rate to 25 percent.

• Transition the tax code to a more competitive system of international taxation [widely understood to mean a territorial tax system].

Elsewhere the plan makes it clear (on page 54, for example) that the Affordable Health Care for America Act (President Obama’s major health care reform) would be repealed. This means the plan would repeal tax increases that were part of the health reform law, including a significant provision reforming the Medicare Hospital Insurance (HI) tax so that it has a higher rate for high-income earners and no longer exempts the investment income of wealthy taxpayers.

Despite all of these proposed tax cuts, Chairman Ryan’s plan also proposes to somehow maintain the level of revenue that will be collected by the federal government under current law.[3]

Ryan’s Budget Plan Is Not Meaningfully Different from His Previous Budget Plans

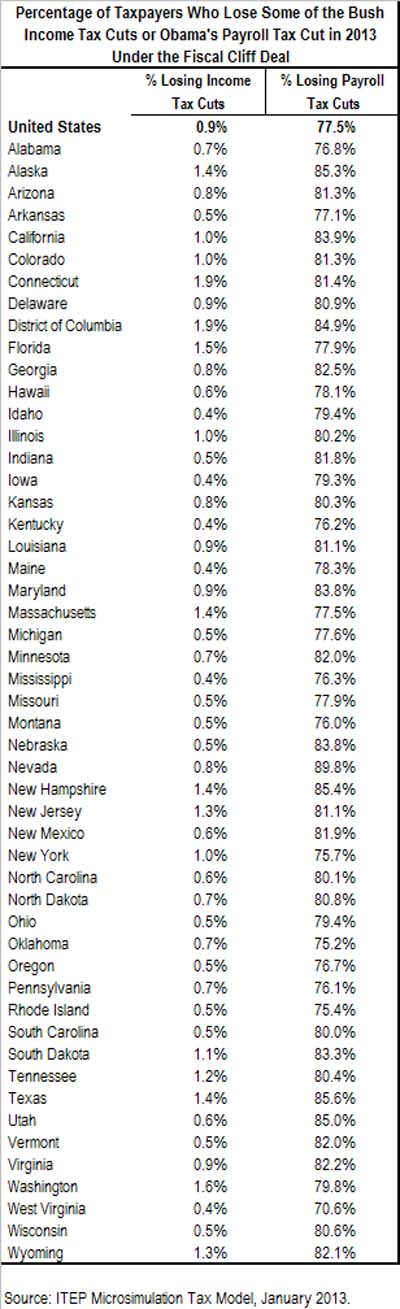

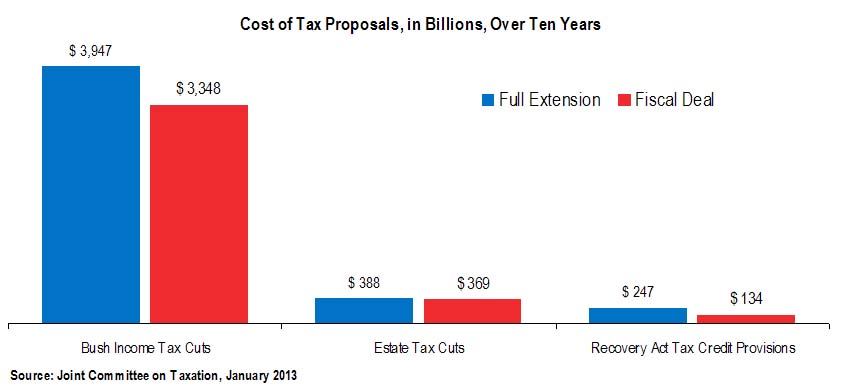

It has been noted that Chairman Ryan’s plan for fiscal year 2014 accepts the level of revenue that the federal government is projected to collect under current law, which includes the recent New Year’s Day deal addressing the “fiscal cliff” by letting some tax rates go up for the very rich and also includes the revenue raised in the Affordable Health Care for America Act. But this is far less impressive than it might sound, for two reasons.

First, Ryan’s plan includes the same revenue-reducing measures — the same tax rate reductions, the same repeal of the AMT, and the same repeal of health care reform — as his previous budget plans. Chairman Ryan simply leaves it to others to decide what tax expenditures to reduce or eliminate to make the entire package revenue-neutral compared to current law.[4]

Second, even the current law level of revenue is widely recognized to be inadequate to meet our nation’s needs. Ryan’s plan notes that under current law, federal revenue will equal 19.1 percent of GDP (19.1 percent of the overall economy) in 2023, and observers have noted that this is more than his previous budgets allowed.[5] But this level of revenue would not have balanced the budget even during the Reagan administration, when federal spending ranged from 21.3 percent to 23.5 percent of GDP. [6] That was at a time when America was not fighting any wars, the baby-boomers were not retiring, and health care costs had not yet skyrocketed the way they have today.

Chairman Ryan’s refusal to raise any more revenue is why his plan must rely on enormous cuts in public investments in order to balance the budget. As others have noted, Ryan’s plan cuts the number of people with health insurance by 40 to 50 million people, cuts $800 billion from the mandatory programs that mostly serve the poor (like Pell Grants, food assistance, the EITC, and Temporary Assistance for Needy Families) and cuts $700 billion from non-defense discretionary spending (like education, transportation, Head Start and housing assistance).[7] Ryan’s budget plan does all this while providing an annual tax cut of at least $200,000 to those with incomes exceeding $1 million.

|

|

Tax Provisions of the Ryan Budget for Fiscal Year 2014 |

||||

|

|

|

|

Specified in Plan |

|

Filling in the Blanks |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Income Tax Rates on Ordinary Income |

|

Two rates, 10% and 25%. |

|

The goal of the Ryan plan is to reduce rates, not raise them, so we assume that income tax rates currently higher than 25% will be replaced with the 25% rate while rates below 25% will all become 10%. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Capital Gains and Dividends |

|

Nothing, except to cite the alleged “double taxation of capital and investment” as one of three factors that “combine to suppress innovation, job creation, and economic growth.” Chairman Ryan’s previous budget plan specifically objected to “raising taxes on investing,” |

|

Currently, the tax brackets in which ordinary income is taxed at 25% and 10% have a 15% and 0% rate, respectively, for capital gains/dividend income. We therefore assume the 25% and 10% brackets in the Ryan plan would have 15% and 0% rates for capital gains and dividends. We do not assume a 20% rate for capital gains and dividends for those with taxable income above $450,000/$400,000 as in current law because this would require a third tax bracket, contradicting Ryan’s goal of having just two brackets. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Tax Expenditures for Individuals |

|

Nothing, except to say that the goal should be to “simplify the tax code” and “reduce the amount of time and resources necessary to comply with tax laws.” Ryan’s previous budget explicitly called for reducing or eliminating tax expenditures to offset the costs of the proposed tax cuts. |

|

To calculate our minimum average net tax cuts, we assume that the very rich must give up all itemized deductions, all credits, the exclusion for employer-provided health care, and the deduction for health care for the self-employed. To calculate our maximum average net tax cuts, we assume none of these tax expenditures are reduced at all. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Hospital Insurance (HI) tax increase in health reform |

|

The plan makes clear that the health reform law would be repealed. |

|

We assume the HI tax reform that was enacted as part of the health reform law would be repealed. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Corporate Tax Statutory Rate |

|

Cut to 25% |

|

We assume corporate tax cuts ultimately are borne by the owners of capital (corporate stocks and other business assets) about half of which are concentrated in the hands of the richest one percent. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Corporate Tax Treatment of Offshore Profits |

|

“Transition the tax code to a more competitive system of international taxation” |

|

This is widely understood to refer to a “territorial” system, meaning a tax system that exempts offshore profits from taxes. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Tax Expenditures for Business |

|

The plan decries the complexity that is generally caused by tax expenditures. It says that “American corporations engage in elaborate tax planning because the current tax code puts them at a competitive disadvantage compared to their foreign competitors,” and that “companies engage in complex transactions purely to reduce their tax burden even when these schemes divert resources from more productive investments.” |

|

To calculate the minimum average net tax cuts, we assume that enough would be eliminated to offset corporate rate cuts and the transition to a territorial system. To calculate the maximum average net tax cut, we assume no tax expenditures are reduced or eliminated. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

[1] Some of the details that need to be filled in for Ryan’s plan would have little effect on the tax bills of very high-income taxpayers. For example, Ryan’s plan does not specify the level of taxable income at which the 10 percent rate would end and the 25 percent rate would begin, and it says nothing about standard deductions and personal exemptions. We assume that all income tax rates currently above 25 percent are replaced with the 25 percent rate, and all rates below the current 25 percent rate are replaced with the 10 percent rate. We also assume no change to standard deductions and personal exemptions. These assumptions make little difference for very high-income taxpayers, because the vast majority of their income would be taxed at the 25 percent rate in any event under Ryan’s plan. But these details could dramatically impact the tax liability of low- and middle-income taxpayers.

[2] The budget plan for fiscal year 2014 does not specify how special income tax rates for investment income and special breaks for savings and investment will be treated, but does cite the alleged “double taxation of capital and investment” as one of three factors that “combine to suppress innovation, job creation, and economic growth.” Ryan’s previous budget plan specifically objected to “raising taxes on investing,” making it extremely difficult to believe Ryan would propose to do so the very next year.

[3] The table on page 78 shows no revenue change, compared to “current policy.” Then the table on page 81 provides the “cross-walk” from CBO’s baseline to what Ryan calls “current policy.” For revenue, the difference is zero dollars.

[4] Chairman Ryan seems eager to specify the tax cuts in his plan, but when it comes to paying for those tax cuts, he becomes deferential to the House Ways and Means Committee (the tax-writing committee). Ryan’s plan claims that it “accommodates the forthcoming work by House Ways and Means Committee Chairman Dave Camp of Michigan. It provides for floor consideration of legislation providing for comprehensive reform of the tax code.” The portion of Ryan’s plan describing tax reform cites, and is nearly identical to, a letter from Camp describing the tax reform Ways and Means Republicans will pursue. Everything described in the letter is consistent with the tax provisions Ryan has proposed in his previous budget plans. Letter from House Ways and Means Committee Republicans to House Budget Committee Chairman Paul Ryan, http://budget.house.gov/uploadedfiles/fy14budgetletterwm.pdf

[5] Suzy Khimm, “Paul Ryan Wants More Revenue,” Washington Post Wonkblog, March 12, 2013. http://www.washingtonpost.com/blogs/wonkblog/wp/2013/03/12/paul-ryan-wants-more-revenue/

[6] Office of Management and Budget, Historical Tables, Table 1.2. http://www.whitehouse.gov/omb/budget/Historicals/

[7] Statement by Robert Greenstein, President, On Chairman Ryan’s Budget Plan, Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, March 12, 2013. http://www.cbpp.org/cms/index.cfm?fa=view&id=3920

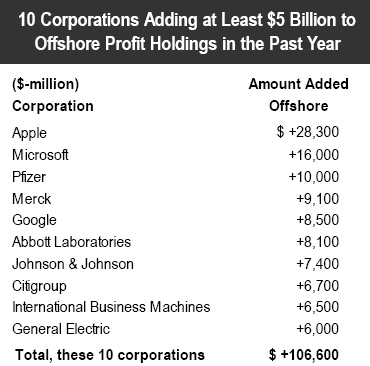

multinational U.S.-based corporations have systematically accumulated staggering amounts of profits offshore. Much if not most of these profits were actually earned in the United States but have been artificially shifted to foreign tax havens to avoid U.S. corporate income taxes.

multinational U.S.-based corporations have systematically accumulated staggering amounts of profits offshore. Much if not most of these profits were actually earned in the United States but have been artificially shifted to foreign tax havens to avoid U.S. corporate income taxes.