Max Baucus, the Senator from Montana who chairs the committee with jurisdiction over our tax code, has made public a portion of his ideas for tax reform. Multinational corporations that have lobbied Baucus for years are unhappy because his proposal would (at least somewhat) restrict their ability to shift jobs and profits offshore. Citizens for Tax Justice and other advocates for fair and adequate taxes are unhappy because his proposal would not raise any new revenue overall — at a time when children are being kicked out of Head Start and all sorts of public investments are restricted because of an alleged budget crisis.

The Need for Revenue-Raising Corporate Tax Reform

Materials released from Senator Baucus’s staff explain that this part of his proposal is “intended to be revenue-neutral in the long-term.” The idea behind “revenue-neutral” corporate tax reform is that Congress would close loopholes that allow corporations to avoid taxes under the current rules, but use the savings to pay for a reduction in the corporate tax rate.

Among the general public, there is very little support for this. The Gallup Poll has found for years that more than 60 to 70 percent of Americans believe large corporations pay “too little” in taxes.

There is almost no public support for the specific idea of using revenue savings from loophole-closing to lower tax rates. A new poll commissioned by Americans for Tax Fairness found that when asked how Congress should use revenue from “closing corporate loopholes and limiting deductions for the wealthy,” 82 percent preferred the option to “[r]educe the deficit and make new investments,” while just 9 percent preferred the option to “[r]educe tax rates on corporations and the wealthy.”

Of course, Baucus also says that he “believes tax reform as a whole should raise significant revenue,” which would mean that reform of the personal income tax would raise revenue. But there are questions about how that can work, given that he also wants to reduce personal income tax rates.

A growing number of consumer groups, faith-based groups, labor organizations and others have called on Congress to raise revenue from reform of the corporate income tax, as well as from reform of the personal income tax. In 2011, 250 organizations, including groups from every state, signed a letter to lawmakers calling for revenue-positive corporate tax reform, and a similar letter in 2012 was signed by over 500 organizations.

CTJ has repeatedly demonstrated that most corporate profits are not subject to the personal income tax and therefore completely escape taxation if they slip out of the corporate income tax. We have also explained that the corporate income tax is a progressive tax, which is needed in a tax system that is not nearly as progressive as most people believe.

The Need to Stop Corporations from Shifting Jobs and Profits Offshore

While CTJ and other tax experts are still going through the fine print of Baucus’s proposal to understand its full impact, it is clear to us that the proposal would stop some American corporations from using offshore tax havens to avoid U.S. taxes as successfully as they do today. Some multinational corporations are upset by this, but that doesn’t in itself mean that Baucus’s proposal is extremely strict.

CTJ has demonstrated that several very large and profitable corporations — like American Express, Apple, Dell, Microsoft, Nike and others — are making profits appear to be earned in offshore tax havens so that they pay no taxes on them at all. Any proposal that makes the code even slightly stricter will cause these companies to pay more and, naturally, cause them to complain bitterly.

These companies are taking advantage of the most problematic break in the corporate income tax, which is “deferral,” the rule allowing American corporations to “defer” (delay indefinitely) paying U.S. corporate income taxes on the profits of their offshore subsidiaries until those profits are officially brought to the United States. Deferral is really a tax break for moving operations offshore or for using accounting gimmicks to make U.S. profits appear to be generated in a country with no corporate income tax (like Bermuda or the Cayman Islands or some other tax haven).

CTJ has long argued that the best solution is to simply repeal deferral and subject all profits of our corporations to U.S. corporate taxes in the year they are earned, no matter where they are earned. (We already have a separate foreign-tax-credit rule that reduces U.S. corporate taxes to the extent that companies pay corporate taxes to other countries, to prevent double-taxation.) Barring this, Congress could at least curb the worst abuses of deferral with the type of reforms proposed by Senator Carl Levin.

The big multinational corporations lobbied Baucus and others to expand deferral into an even bigger break, an permanent exemption for offshore profits, often called a “territorial” tax system, which CTJ and several small business groups, consumer groups and labor organizations have always opposed.

Baucus did not propose either approach. His proposal is somewhat like a territorial tax system except that he would place a minimum tax on the offshore profits of American corporations, which would take away much of the advantage that the corporations thought they might obtain after their years of lobbying. American multinational corporations would be required to pay a minimum level of tax on their offshore profits, during the year that they are earned.

But if a corporation is paying corporate taxes to a foreign government at a rate as high or higher than the U.S. minimum tax, there would never be any U.S. taxes on the profits generated in that country. This means that offshore profits of American corporations would still be subject to a lower tax rate than domestic profits, which may preserve some incentive to shift jobs and profits offshore.

Baucus proposes two different versions of a minimum tax. One would require that profits generated in other countries be taxed at a rate that is at least 80 percent of the regular U.S. corporate tax rate. Baucus has not yet revealed what corporate tax rate he will propose, but if one assumes it is 28 percent, that would mean that the foreign profits must be taxed at a rate of at least 22.4 percent. If they are taxed by the foreign country at a rate of, say, 18 percent, that would mean the corporation would pay U.S. corporate taxes of 4.4 percent. (18+4.4=22.4)

The second option Baucus offers would require that “active” profits generated abroad be taxed at a rate that is 60 percent of the U.S. tax rate while “passive” profits generated abroad be taxed at the full U.S. rate (both before foreign tax credits). The concept of “active” income and “passive” income already is a major part of our tax code, but Baucus would define them differently for this option. The basic idea is that “passive” income (like interest payments, rents and royalties) is income that is extremely easy to move from one subsidiary to another and therefore easily used for tax avoidance if it’s not taxed at the full U.S. rate.

The Baucus proposal has several other innovations that are too numerous to fully explain here. To give one example, the proposal says that if an American corporation has a subsidiary in another country that earns profits by selling to the U.S. market, those profits would be subject to the full U.S. corporate tax rate in the year that they are earned. How well this would work might depend heavily on how easily this can be administered.

Since there are no public estimates of the revenue impacts of the provisions Baucus has proposed, it is not yet clear how important many of them are. Stay tuned as we examine this proposal and learn more.

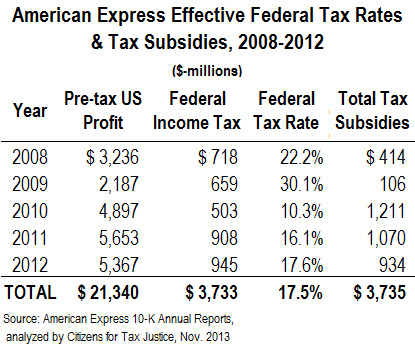

Even on the $21.3 billion in pretax profits that American Express officially earned in the U.S. over the past five years, the company has paid only half the 35 percent federal statutory tax rate. This means that over the past five years, American Express received over $3.7 billion in tax subsidies through the US tax code.

Even on the $21.3 billion in pretax profits that American Express officially earned in the U.S. over the past five years, the company has paid only half the 35 percent federal statutory tax rate. This means that over the past five years, American Express received over $3.7 billion in tax subsidies through the US tax code.

Voters in 36 states will be choosing governors next year. Over the next several months, the Tax Justice Digest will be highlighting 2014 gubernatorial races where we expect taxes to be a key issue. Today’s post is about the race for the Governor’s mansion in Wisconsin.

Voters in 36 states will be choosing governors next year. Over the next several months, the Tax Justice Digest will be highlighting 2014 gubernatorial races where we expect taxes to be a key issue. Today’s post is about the race for the Governor’s mansion in Wisconsin.  Update: Pennsylvania Governor Tom Corbett signed the gas tax increase described below into law on November 25, 2013.

Update: Pennsylvania Governor Tom Corbett signed the gas tax increase described below into law on November 25, 2013.

The District of Columbia’s Tax Revision Commission

The District of Columbia’s Tax Revision Commission