Two years ago, the Koch-brothers-backed group Americans for Tax Reform and anti-tax advocate Grover Norquist launched an aggressive effort in Tennessee to eliminate the Hall Tax, a modest tax on capital gains and dividends that primarily falls on the very wealthiest Tennesseans.

That effort failed to produce results at the time, but like Kudzu, “the vine that ate the South,” the invasive idea proved difficult to stop once it took root in the Tennessee Legislature. With continued urging from outside groups and the state running a budget surplus this year, lawmakers again considered various proposals to outright eliminate the tax or phase it out over a number of years. Still, some remained concerned about giving life to a process that would be difficult to reverse and would choke off funding needed for state and local services.

But in a compromise that advanced unanimously through the Senate Finance, Ways, and Means Committee on Monday and continues to gain co-sponsors, Tennessee legislators are hoping they can introduce just a little bit of this Koch Kudzu this year and manage its spread in future years.

Can’t See the Forest for the Kudzu

While passing a measure to eliminate a tax that raises millions each year may be politically expedient during a year with a budget surplus, it is shortsighted.

The compromise reduces the Hall Tax rate from 6 percent to 5 percent in 2016 and declares the General Assembly’s intent to continue reducing the tax by 1 percentage point per year until it is extinct in 2021. This would reduce state and local revenues by about $57 million in the first year and $341 million per year if full repeal happens.

Revenue from the Hall Tax funds many vital state services and are also shared with Tennessee counties and municipalities. Ultimately these local governments could lose all of their Hall Tax revenue, which is currently about $119 million annually and used to pay for city streets, local police officers, county roads, etc. Once that revenue disappears, Tennesseans will either face cuts to those services or increases in their local property taxes.

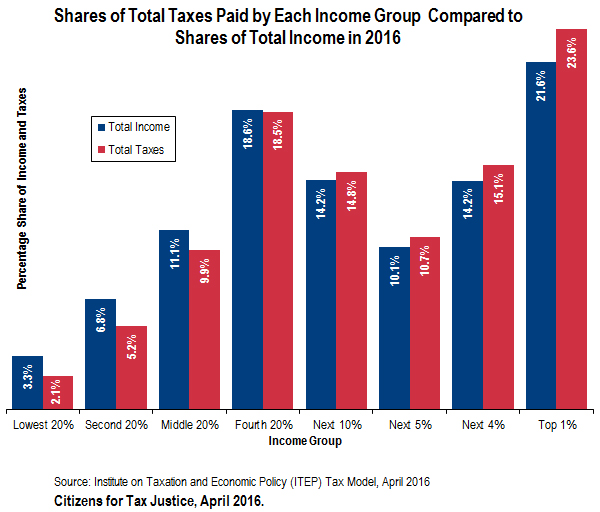

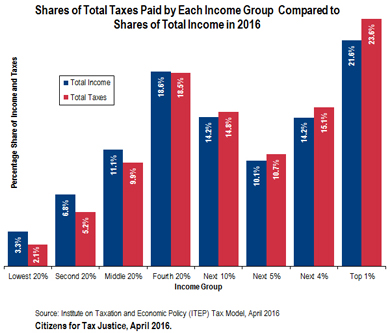

Moreover, an Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy analysis finds that only those in the upper reaches of the Tennessee economy would see any significant benefit from the tax cuts. In just the first year, the wealthiest 1 percent of Tennesseans (with an average income of $1.2 million) would receive tax cuts averaging $870, while a majority of Tennesseans would see no benefit at all (see graph).

More specifically, as we have detailed in our full report on Hall Tax repeal, only 14 percent of the total tax cut would flow to households among the bottom 95 percent of earners, while the top 5 percent of households would receive 61 percent of the benefit, and the federal government would collect the remaining 25 percent due to higher federal income tax payments by Tennesseans who would not be able to deduct as much in state taxes from their federal income taxes.

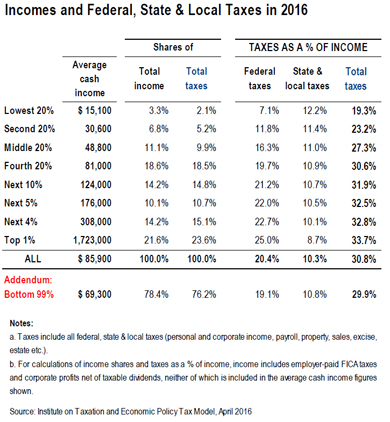

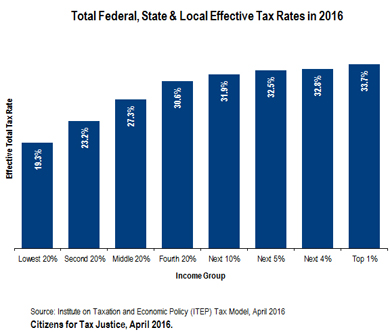

It should be noted that the Tennessee tax system is more regressive (meaning it captures a greater share of income from the lowest-income residents than the wealthiest) than all but six other states. In fact, the average tax rate for the bottom 20 percent of taxpayers is 10.9 percent compared to just 3 percent for the top 1 percent. Reducing or repealing the Hall Tax would make this imbalance even worse.

Alaska is grappling with one of the most serious budget shortfalls in the nation. The state currently faces a budget gap exceeding $4 billion and current revenues are expected to cover just 25 percent of the state’s costs, despite major spending cuts enacted in recent years.

Alaska is grappling with one of the most serious budget shortfalls in the nation. The state currently faces a budget gap exceeding $4 billion and current revenues are expected to cover just 25 percent of the state’s costs, despite major spending cuts enacted in recent years.