This is the fourth installment of our six-part series on 2016 state tax trends. An overview of the various tax policy trends included in this series is here.

Tax shifts lower or eliminate one tax in exchange for increasing a different tax. While tax shifts can come in different forms, recent tax shift proposals have typically called for the reduction or elimination of personal and corporate income taxes and expanded consumption taxes to make up some or all of the lost revenue. Despite the detrimental effect these tax shifts have on working families and state budgets down the road, they’ve been quite popular among states. Unfortunately, this trend continues in 2016, with several states considering tax shift proposals right out of the gate.

Tax shifts lower or eliminate one tax in exchange for increasing a different tax. While tax shifts can come in different forms, recent tax shift proposals have typically called for the reduction or elimination of personal and corporate income taxes and expanded consumption taxes to make up some or all of the lost revenue. Despite the detrimental effect these tax shifts have on working families and state budgets down the road, they’ve been quite popular among states. Unfortunately, this trend continues in 2016, with several states considering tax shift proposals right out of the gate.

This year we are keeping our eye on an emerging sub-trend in tax shifts—leveraging the need for states to make long-overdue improvements to transportation infrastructure in order to get tax cuts that disproportionately benefit the highest-income households. We saw this in Michigan this past November, where lawmakers approved increases to gas taxes and vehicle registration fees but also offset new revenue with future cuts to the state’s top income tax rate. While an increase in transportation funding has been long-overdue in many states, these tax shift proposals have the effect of doing so at the expense of other critical state investments including higher education, public health, and safe communities.

Here’s a list of states we are watching in 2016:

Arizona. Eliminating the income tax and replacing lost revenues with a higher sales tax is still a priority for Gov. Doug Ducey and lawmakers like chairman of the Ways and Means Committee Representative Darin Mitchell. Details are still forthcoming, but the governor has stood by his campaign pledge to drive the income tax rate as close to zero as possible. In Arizona, the bottom 20 percent of taxpayers already pay three times as much in taxes as a share of their income as do the top one percent. Further tax shifts from the income tax to the sales tax would be a disastrous move for tax fairness, increasing taxes on low- and middle-income families while providing substantial tax cuts to those with high-incomes.

Mississippi. There was no shortage of significant tax proposals last year, including the Senate’s proposal to reduce income tax rates and franchise taxes, the governor’s tax cut for working families, and the House’s proposal to eliminate the income tax. However, the session ended last year without a compromise plan that could garner enough votes to win approval. Given a new supermajority among republican lawmakers thanks to November elections, the state is almost certain to see some sort of major tax shift this year.

Mississippi’s transportation infrastructure needs may very well provide the ticket lawmakers need to enact their desired cuts. It’s been 27 years since Mississippi last raised its gas taxes, making proposals to reform fuel taxes this year most welcome and long-overdue. Plans to raise at least $300 million for road and bridge maintenance however, are unlikely to move forward without offsetting tax cuts. Even Governor Bryant is calling for “an equal and sufficient tax reduction” to offset any proposed tax increases. His preferred plan is a “blue collar” tax cut in the form of a nonrefundable EITC (the same plan he advocated for last year), but he is also amenable to a reduction or elimination of the state’s corporate franchise tax. While a tax cut for working families would be an appropriate and targeted policy to pair with a regressive tax increase, House and Senate lawmakers are likely to propose less targeted and more broad-based tax cuts that could result in tilting the state’s already upside down tax system more in favor of the wealthy.

Tax Shifts for Transportation a Bridge to Nowhere

Indiana. To make it more palatable for lawmakers to fund repairs for roads and bridges, House Republicans slipped a phased-in 5 percent income tax cut into a transportation package that passed the House this past Tuesday. Intending to increase funds available for infrastructure improvements, HB 1001 raises the state’s gasoline excise tax by 4 cents per gallon and the tax on diesel fuel by 7 cents. It also increases the cigarette tax by $1 per pack. The revenue potential of this bill, however, is undermined by the reduction of the personal income tax rate down to 3.06 percent over eight years. The proposal also exacerbates the unfairness of Indiana taxes: an ITEP analysis of the proposal found that the average taxpayer among the bottom 80 percent of earners would see a tax hike while the wealthiest 20 percent would benefit from a tax cut.

Georgia. What we’re seeing in Georgia is an attempt to enact a tax shift over two legislative sessions. Last year, the state enacted significant gas tax reform amongst other measures, raising $1 billion in transportation revenue. Part of the transportation package created a Special Joint Committee on Revenue Structure, which was tasked with identifying tax cuts. Due to a failure of the House to appoint their members, the committee did not convene and no tax reform plan was created. As a result of this inaction and in direct response to the prior year’s tax increase, Senator Judson Hill has introduced his own tax-cutting measures. Senate Bill 280’s primary effect is to flatten Georgia’s personal income tax to a single rate of 5.4 percent. Senate Resolution 756 requires a constitutional amendment that would bring down this rate even further. Both measures would deprive the state of needed revenue and require it to inevitably to make up these losses through more regressive sources.

New Jersey. Facing a drying up Transportation Trust Fund, lawmakers continue to talk this year about increasing the gas tax. However, Governor Christie has said that he won’t consider raising the gas tax unless lawmakers agree to other tax cuts, specifically raising the exemption level of the estate tax or eliminating the tax altogether. In contrast to the governor’s claim that the estate tax is a burden on the middle class, a new report from the New Jersey Policy Perspectives shows that just four percent of estates are subject to the tax and that cutting the tax could seriously threaten resources needed to fund important building blocks of a strong economy such as higher education, health care, and safe communities.

South Carolina. South Carolina is preparing to debate and vote on a road repair plan in the coming weeks. The proposed law would raise an estimated $700 million each year in new revenue once fully phased in through an increase to the gas tax and other transportation related-fees, but this amount would be offset by $400 million from a combination of income tax and business property tax cuts. While there are some targeted income tax breaks that would benefit working families, including the creation of a 3.5% refundable Earned Income Tax Credit, the overall effect of the plan is somewhat regressive. There may be talk of offsetting the gas tax increase with cuts to the sales tax instead of the income tax, which, all things being equal, would be a preferable shift since it would favor cuts for middle-income earners over the wealthiest. But, most importantly, like in every other state considering this brand of tax shift, increasing one set of fees and taxes to support new funding for transportation while cutting taxes that support public education and health care is not a sensible or sustainable policy idea.

Up Next

Not all tax cuts and shifts are bad policy. Building on the momentum from 2015 reforms, many states are headed into their legislative sessions looking to address poverty and inequality through targeted tax measures. Stay tuned for the next blog post in our series for a more in-depth look at what states are addressing poverty and inequality through enacting or strengthening tax credits for working families.

Yesterday Congress passed a bill, which President Obama is expected to sign, that will ban states from imposing taxes on Internet access. The so-called “Internet Tax Freedom Act” (ITFA) was originally enacted in 1998 as a temporary measure meant to assist an “infant industry.” Now, however, it is being made permanent for exactly the opposite reason: because the Internet is “a resource used daily by Americans of all ages, across our country,” according to Sen. Majority Leader Mitch McConnell. The bill effectively forces a tax cut onto the states, without any direct cost to the federal government. It’s Congress’ favorite kind of tax cut: one that it does not need to pay for.

Yesterday Congress passed a bill, which President Obama is expected to sign, that will ban states from imposing taxes on Internet access. The so-called “Internet Tax Freedom Act” (ITFA) was originally enacted in 1998 as a temporary measure meant to assist an “infant industry.” Now, however, it is being made permanent for exactly the opposite reason: because the Internet is “a resource used daily by Americans of all ages, across our country,” according to Sen. Majority Leader Mitch McConnell. The bill effectively forces a tax cut onto the states, without any direct cost to the federal government. It’s Congress’ favorite kind of tax cut: one that it does not need to pay for. As we explain in our annual

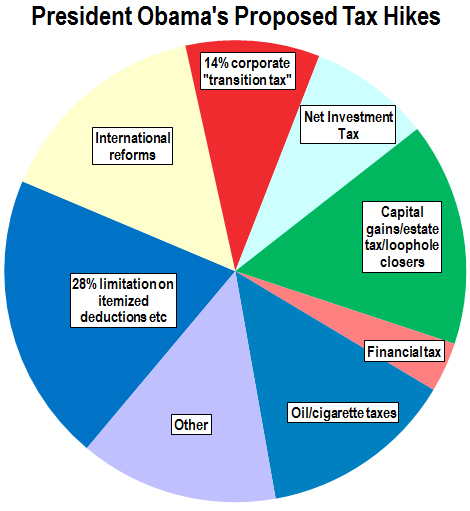

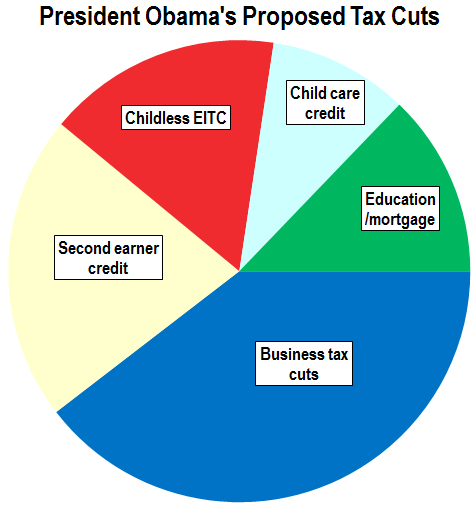

As we explain in our annual  President Obama’s budget would raise about $3.2 trillion in new tax revenues over the next ten years from a diverse set of sources, primarily affecting wealthier taxpayers and large corporations, but also including an “oil fee” and a cigarette tax hike that would have an impact on middle- and low-income families.

President Obama’s budget would raise about $3.2 trillion in new tax revenues over the next ten years from a diverse set of sources, primarily affecting wealthier taxpayers and large corporations, but also including an “oil fee” and a cigarette tax hike that would have an impact on middle- and low-income families.

As

As

The recently released

The recently released  Tax shifts lower or eliminate one tax in exchange for increasing a different tax. While tax shifts can come in different forms, recent tax shift proposals have typically called for the reduction or elimination of personal and corporate income taxes and expanded consumption taxes to make up some or all of the lost revenue. Despite the detrimental effect these tax shifts have on working families and state budgets down the road, they’ve been

Tax shifts lower or eliminate one tax in exchange for increasing a different tax. While tax shifts can come in different forms, recent tax shift proposals have typically called for the reduction or elimination of personal and corporate income taxes and expanded consumption taxes to make up some or all of the lost revenue. Despite the detrimental effect these tax shifts have on working families and state budgets down the road, they’ve been