January 1, 2000 01:01 PM | Permalink |

Click here to see this analysis in PDF format.

Introduction & summary:

The current federal income tax system does not tax the earnings of low- and moderate-income working families with children. In fact, the vast majority of such families actually enjoy “negative” income taxes. In other words, their earnings are higher after income taxes than before income taxes. For example, a single mother with one child earning

Current Income Taxes on Working Families

Who Get the Earned-Income Tax Credit |

| Income Group |

% of EITC Families |

Average Income Tax Now |

| Less than $10,000 |

16.8% |

$ –1,829 |

| $10-20,000 |

41.9% |

–2,343 |

| $20-30,000 |

34.5% |

–1,002 |

| $30,000+ |

7.7% |

–497 |

| All EITC families |

100.0% |

$ –1,658 |

$18,000 a year in wages before taxes makes $19,004 after federal income taxes.

Of fiscal necessity, the income tax rebates enjoyed by low- and moderate-income working families are phased out above certain income levels. An unfortunate side effect is that some working families can face quite high “marginal” income tax rates over the phase-out range, even though their actual income taxes paid remain very low or negative. To illustrate:

- As noted above, a single mother with one child earning $18,000 enjoys a federal income tax rebate of $1,004. But if she earns an additional $100, her income tax rebate falls by $31, to $973–a marginal income tax rate on that $100 of 31%.

- Likewise, a single mother with two children earning $22,000 gets a federal income tax rebate of $1,701. But if she earns an additional $100, her rebate falls by $36, to $1,665, a marginal income tax rate on that $100 of 36%.

These high “marginal” income tax rates worry some tax analysts.(1) In theory, a high marginal tax rate can discourage work effort in some cases by reducing the rewards for working versus goofing off. Of course, in theory a high marginal tax rate can also encourage more work effort in some cases, since it takes more work to make enough money to support one’s family. In any event, here is an example of how high marginal tax rates can coexist with very low average tax rates under current law:

- A single mother with one child with a wage of $9 an hour will earn $18,000 a year before taxes at a full-time job. After federal income taxes, her hourly wage will average $9.50 an hour. So her average federal income tax rate is -5.6%. If she works an additional 11 hours at $9 an hour (earning $100 more in gross pay), her federal income tax rebate will fall by $31. That means an after-tax hourly rate of only $6.21 an hour on the additional $100 in earnings (before payroll taxes and state and local taxes). This is true even though the mother’s total pay after federal income taxes of $19,073 is still higher than her pretax pay of $18,100 (and her average federal income tax rate is -5.4%).

The following table and chart offer more illustrations of average and marginal tax rates on low- and moderate income single parents with one child under current law.

George W. Bush’s tax plan and working families: To justify the large federal tax cut he proposed in December 1999, Gov. George W. Bush emphasizes the positive effects that his plan will have in reducing marginal tax rates on low- and moderate-income working families:

“[B]ecause the benefit of the Earned Income Credit diminishes as a worker’s income increases, a single mother with two children on the outskirts of poverty will lose half of any additional dollar she earns (taking into account social insurance taxes and state income taxes). The benefit of taking an extra training course or working an extra shift is cut in half by the government. . . . Lowering these barriers to the middle class is one of Governor Bush’s top priorities.”(2)

There is no doubt that the Bush tax plan would reduce marginal tax rates on some working families with children. Whether this can be considered one of the “top priorities” of the Bush tax plan is another question, however.

As is explained in more detail below, the Bush proposal would reduce marginal tax rates for about a fifth of the 13.9 million working families with children that now get the earned-income tax credit. These changes will help those families, but their effects should not be overstated. Bush’s proposed tax cuts for working families with children who get the earned income tax credit total $2.6 billion a year (at 1999 levels). That equals only one percent of these families’ incomes, and averages only $182 per family.

Put another way, the $2.6 billion in total tax cuts that Bush proposes for moderate-income working families with children is only 1½ percent of the total annual reduction in taxes that Bush proposes. In contrast, 62 percent of Bush’s proposed tax cuts–a total of $105 billion a year–is targeted to the best off 12.7 million taxpayers.(3)

Detailed Analysis

Current Income Taxes on Moderate-Income Working Families

Under current law, federal income taxes on low- and moderate-income working families with children are very low. In fact, the vast majority of low- and moderate-income working families with children actually enjoy “negative” income taxes. For example,

- A couple with two children does not have a positive income tax until earnings exceed $28,215. A single parent with two children does not pay income tax until earnings exceed $26,720.

- A couple with one child does not have a positive income tax until earnings exceed $22,985. A single parent with one child does not pay income tax until earnings exceed $21,245.

Below these income levels, low- and moderate-income working families receive actual tax rebates, due to the refundable earned income tax credit. For example, couples and single parents with two children earning $20,000 get a tax rebate (a negative income tax) of $2,232. Overall, the average federal income tax rebate for working families with children earning less than $27,500 a year is $1,755. Most of the families receiving these rebates (two-thirds) are headed by single parents.

Marginal Tax Rate Issues:

Although actual income taxes are negative for most moderate-income working families, “marginal” income tax rates–the amount of tax paid or tax rebate lost on additional earnings–can occasionally be quite high. Marginal income tax rates can reach 36 percent for some moderate-income families with two children (and in rare cases for families with three or more children), and climb as high as 31 percent for some one-child families.

- For single parents with two children, the 36 percent marginal income tax rate applies to earnings between $21,267 and $30,600. For couples with two children, the range for the 36 percent rate is between $24,867 and $30,600.

- For single parents with one child, the 31 percent marginal income tax rate applies to earnings between $15,183 and $26,930. For couples with one child, the 31 percent range is between $18,785 and $26,930.

These high marginal income tax rates stem primarily from the phase-out rules for the earned-income tax credit. The EITC is a refundable tax credit worth as much as $3,820 to families with two or more children and up to $2,312 for families with one child. The credit is phased out, however, above $12,460 in earnings. Specifically:

- The EITC is reduced by 21 cents for each dollar of additional earnings between $12,460 and $30,600 for families with two or more children.

- The EITC is reduced by 16 cents for each dollar of additional earnings between $12,460 and $27,930 for families with one child.

The rest of the high marginal income tax rates on some moderate-income working families stems from the 15 percent tax bracket. The starting points for the 15 percent bracket vary by family size and type. For instance:

- For single parents with two children, the 15 percent bracket begins at $21,267 in earnings. For couples with two children, it starts at $24,867.

- For single parents with one child, the 15 percent bracket begins at $15,183. For couples with one child, it starts at $18,785.

As noted, however, despite the high “marginal tax rates,” actual income tax liabilities for moderate-income working families with children are very low, in fact, generally negative. But some analysts worry about the possible disincentive effects of the high marginal income tax rates that some of these families face. Indeed, counting Social Security and Medicare payroll taxes, the marginal rate on increased earnings can exceed 50 percent in some cases (counting both the employer and employee shares of the 15.3 percent total payroll tax).

The Bush Tax Plan

In part to try to address the potential disincentive effects of these high marginal tax rates on moderate-income working families, the Bush tax plan offers two proposals:

- A new 10 percent tax bracket for the first $12,000 in taxable income for couples and $10,000 in taxable income for single parents.

- Doubling of the per-child tax credit for children under 17, from $500 to $1,000.

These two changes(4) would cut marginal tax rates on some EITC families by reducing or eliminating the ranges of income in which the 15 percent tax bracket overlaps with the 16 percent or 21 percent phase-out rates for the earned income tax credit. (The EITC phase-out rates and ranges themselves would be unaffected.)

As a result, the current 36 percent marginal tax rate that some two-child moderate-income working families face would be eliminated. Those families now in the 36 percent marginal rate would see their marginal rate drop to 21 percent (just the EITC phase-out rate). In addition, the range of income now subject to the 31 percent rate (some one-child families) would be substantially narrowed. Specifically:

- The 36 percent marginal tax rate faced by two-child couples making between $24,867 and $30,600 and by two-child single parents making between $21,267 and $30,600 would drop to 21 percent.

- For single parents with one child, the range of income subject to the 31 percent marginal tax rate, which is now from $15,183 to $26,930, would be narrowed to a range of $21,850 to $26,930.

| Marginal Tax Rate Reductions for EITC Families Under the Bush Tax Plan |

| |

Married Couples |

Single Parents |

| |

1 Kid |

2 Kids |

1 Kid |

2 Kids |

3 Kids |

| EITC Phase-Out: |

16.0% |

21.1% |

16.0% |

21.1% |

21.1% |

| Starts |

$ 12,460 |

$ 12,460 |

$ 12,460 |

$ 12,460 |

$ 12,460 |

| Ends |

26,930 |

30,600 |

26,930 |

30,600 |

30,600 |

| Income Tax before EITC Starts |

| Current law rate of |

15% |

15% |

15% |

15% |

15% |

| Starts at |

18,785 |

24,867 |

15,183 |

21,267 |

24,130 |

| Bush plan rate of |

10% |

15% |

15% |

15% |

15% |

| Starts at |

25,450 |

35,533 |

21,850 |

31,267 |

40,683 |

| Overlaps: |

| Current law: From: |

$ 18,785 |

$ 24,867 |

$ 15,183 |

$ 21,267 |

$ 24,130 |

| To: |

26,930 |

30,600 |

26,930 |

30,600 |

30,600 |

| Width of Range: |

8,145 |

5,733 |

11,747 |

9,333 |

6,470 |

| Bush plan: From |

$ 25,450 |

no |

$ 21,850 |

no |

$ 27,567 |

| To: |

26,930 |

overlap |

26,930 |

overlap |

30,600 |

| Width of Range: |

1,480 |

none |

5,080 |

none |

3,033 |

| Dollar Change in Overlap Range under Bush: |

$ –6,665 |

$ –5,733 |

$ –6,667 |

$ –9,333 |

$ –3,437 |

| % of all EITC families of each type with marginal rate cuts under Bush (20.6% of all EITC families) |

32.2% |

17.9% |

23.3% |

23.3% |

8.3% |

| Note: income tax rates above the end of the EITC phase-out range are not shown. |

For single parents with one child, the range of income subject to the 31 percent marginal tax rate, which is now from $15,183 to $26,930, would be narrowed to a range of $21,850 to $26,930.

- For one-child married couples, the 31 percent marginal rate that now applies between $18,785 and $26,930 would be eliminated. The marginal tax rates on this range of income under the Bush plan would be 16 percent on earnings between $18,785 and $25,500 and 26 percent on earnings between $25,500 and $26,930.

The charts that follow illustrate the effects of the Bush proposals on marginal rates faced by moderate-income single parents.

Changes in actual income taxes under the Bush plan: The reductions in marginal tax rates proposed by Bush would also increase tax rebates (or reduce taxes paid) for some moderate-income working families with children. The following charts illustrate those effects on single parents:(5)

The Bush Bottom Line: Overall, the Bush proposal would reduce marginal tax rates for

Effects of All Bush Tax Cuts on All

Families With Children Who Get the EITC |

| Income Group |

Millions of

EITC

Families |

% of all

EITC

families |

Average

Bush

Tax Cut |

| Less than $10,000 |

2.3 |

16.8% |

$ — |

| $10-20,000 |

5.8 |

41.9% |

–47 |

| $20-30,000 |

4.8 |

34.5% |

–355 |

| $30,000+ |

1.1 |

7.7% |

–539 |

| All EITC families |

13.9 |

100.0% |

$ –182 |

| Bush tax cuts (annual at 1999 levels) |

| Total amount |

$ –172.1 billion |

| Amount to EITC families |

–2.6 billion |

| Share to EITC families |

1.5% |

Figures include effects of:

new 10% tax bracket; doubling the per child tax credit to $1,000;

a deduction for two-earned couples;

and an above-the-line charitable deduction for non-itemizers.

Income classifier includes income that is not part of AGI. |

about 2.9 million of the 13.9 million working families with children that now get the earned-income tax credit. Another 2.6 million EITC families would get tax reductions or larger tax rebates under the Bush plan, although their marginal tax rates would not be affected.

These changes will be helpful to the affected families, but their effects should not be overstated. The sum total of all of Bush’s proposed tax cuts on working families with children who get the earned income tax credit is $2.6 billion a year (at 1999 levels),(6) equal to only one percent of these families’ incomes, and averaging only $182 per family.

Put another way, that $2.6 billion in total tax cuts for moderate-income working families with children is only 1.5% of the total annual reduction in taxes that Bush has proposed. That compares to 62 percent of Bush’s tax cuts–$105 billion a year–that is targeted to the best off 12.7 million taxpayers.

![]()

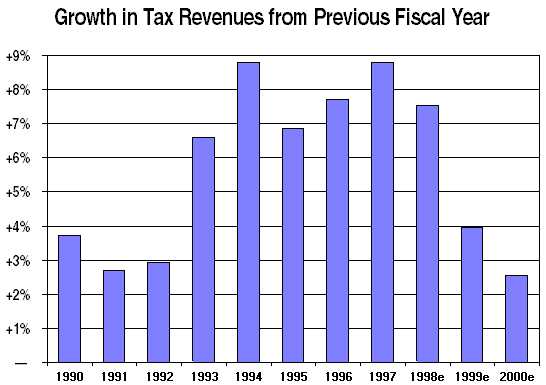

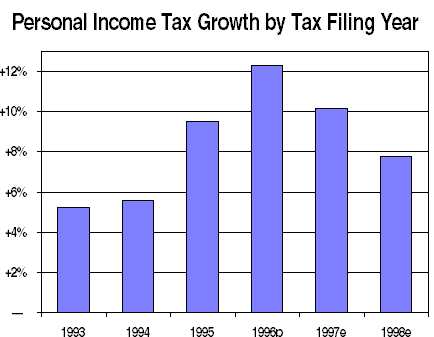

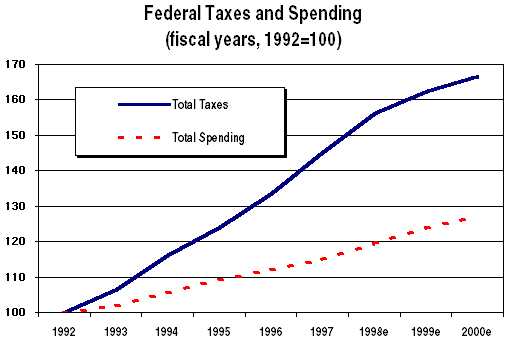

upwards of $50 billion more than it takes in this fiscal year.

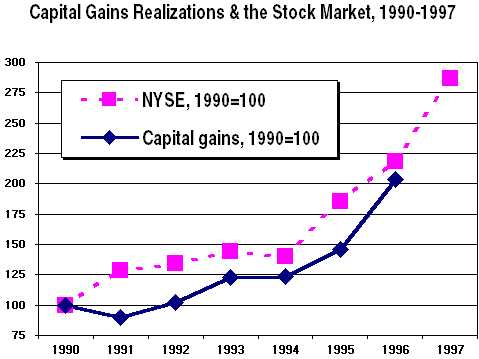

upwards of $50 billion more than it takes in this fiscal year. Indeed, GOP leaders are reportedly pressuring the nonpartisan analysts at the Congressional Budget Office and the Joint Committee on Taxation to adjust their tax models so that they will show an additional capital gains tax cut as a huge revenue raiser. There are several flaws in this theory, however.

Indeed, GOP leaders are reportedly pressuring the nonpartisan analysts at the Congressional Budget Office and the Joint Committee on Taxation to adjust their tax models so that they will show an additional capital gains tax cut as a huge revenue raiser. There are several flaws in this theory, however.

Sources for all data and estimates: Internal Revenue Service for calendar year tax data through tax year 1996 (the latest available). Office of Management and Budget for tax and spending data for fiscal years through 1997. Treasury Department “Monthly Budget Statements” for tax revenues and spending by month in fiscal 1998 through May. Office of Management and Budget (May 1998) and Congressional Budget Office (June 1998) for revenue and spending estimates beyond May of 1998.

Sources for all data and estimates: Internal Revenue Service for calendar year tax data through tax year 1996 (the latest available). Office of Management and Budget for tax and spending data for fiscal years through 1997. Treasury Department “Monthly Budget Statements” for tax revenues and spending by month in fiscal 1998 through May. Office of Management and Budget (May 1998) and Congressional Budget Office (June 1998) for revenue and spending estimates beyond May of 1998.