While most computer users are likely familiar with Adobe products, they are probably not aware of the company’s tax-dodging practices.

While most computer users are likely familiar with Adobe products, they are probably not aware of the company’s tax-dodging practices.

The maker of the ubiquitous PDF reader and Flash software earlier this week released its annual report, which revealed the company is rapidly diverting profits offshore. Its stash of “permanently reinvested” foreign earnings jumped by $400 million in 2015, from $3.3 to $3.7 billion. The number alone is quite impressive considering the company’s total foreign income was just $284 million last year.

Adobe also disclosed that if it repatriated these offshore profits to the United States, it would pay about a 27 percent federal tax rate. This essentially is an indirect admission that wherever these paper profits are housed, the company is paying a foreign tax rate of just 8 percent (the difference between the 35 percent U.S. rate and the tax on these profits the company would face once it repatriates these earnings).

Very few countries have corporate tax rates of 8 percent or lower. What’s particularly deceptive about Adobe’s disclosures is that none of the countries where Adobe admits having legitimate foreign subsidiaries even approach this low tax level. This suggests the company is hiding behind lax Securities and Exchange Commission standards that only require companies to report “significant” offshore subsidiaries.

Of course Adobe is not alone in this brazen tax avoidance. Apple, Microsoft, Google, Nike, Pfizer and dozens of other big multinationals also gratuitously have shifted their profits out of the United States into no-tax or extraordinarily low-tax countries to dodge U.S. taxes.

In this context, the corporate “reforms” being pushed by lawmakers make no sense and are clearly no more than an ineffective giveaway. Republican leaders in the House and Senate signaled this week that they intend to seek international tax reform in 2016. The contours of the plan are familiar: offering companies with offshore holdings a special “tax holiday” to bring back their offshore profits at a sharply reduced rate, moving to a “territorial” system that exempts all foreign profits from tax, and a sharply lower tax rate on all domestic corporate profits going forward.

As always, what’s striking about this broad plan is how disconnected it is with the actual behavior of U.S. multinationals as revealed in their financial reports, and how it fails to acknowledge bigger-picture issues. If large corporations can achieve single-digit tax rates by pretending to earn their profits in tax haven countries, lowering the federal corporate tax to 30 or even 25 percent will not fix the problem. The only way to take away the incentive for corporations to pretend their U.S. profits are being earned in foreign tax havens is to end the deferral of tax on foreign profits. Sadly, that’s exactly the opposite of the path indicated by congressional tax writers.

Ending months of media speculation, General Electric

Ending months of media speculation, General Electric  Hillary Clinton on Tuesday

Hillary Clinton on Tuesday

Late last year, the New York Times published an article revealing

Late last year, the New York Times published an article revealing

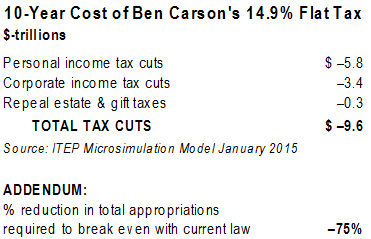

Presidential candidate Ben Carson, who had

Presidential candidate Ben Carson, who had

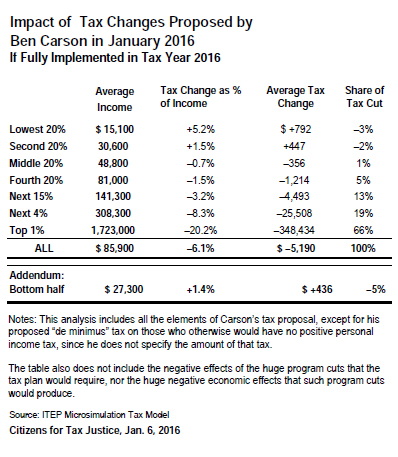

A Citizens for Tax Justice (CTJ) analysis of presidential candidate Ben Carson’s recently released

A Citizens for Tax Justice (CTJ) analysis of presidential candidate Ben Carson’s recently released