Sen. Rand Paul (R-KY) outlined the broad contours of his plan for restructuring the federal tax system in a Wall Street Journal op-ed today. He proposes replacing the personal income tax and payroll taxes with a flat-rate14.5 percent income tax, and replacing the corporate income tax with what amounts to a value-added tax (VAT). A CTJ preliminary analysis of the plan finds that it would likely cost $1.2 trillion a year and $15 trillion over a decade.

Sen. Rand Paul (R-KY) outlined the broad contours of his plan for restructuring the federal tax system in a Wall Street Journal op-ed today. He proposes replacing the personal income tax and payroll taxes with a flat-rate14.5 percent income tax, and replacing the corporate income tax with what amounts to a value-added tax (VAT). A CTJ preliminary analysis of the plan finds that it would likely cost $1.2 trillion a year and $15 trillion over a decade.

Paul’s plan would repeal the progressive personal income tax, the estate tax, and the federal payroll tax and replace them with a single 14.5 percent “flat tax” on all types of personal income. The plan would keep a few features of the current tax code, including itemized deductions for mortgage interest and charitable contributions and the Earned Income Tax Credit, and would create a large “no tax floor” by exempting the first $50,000 of income (for married couples) from the new income tax. A CTJ analysis estimates that the switch from the progressive personal income tax to the new flat-rate tax on personal income would cost more than $700 billion in 2016 alone.

Repealing payroll taxes, the estate tax and all customs duties would cost an additional $1.6 trillion, leaving a $2.3 trillion hole in the budget. Paul proposes to fill some of that hole with a 14.5 percent “business activity tax,” which appears to be conceptually identical to a VAT. While it’s uncertain exactly what would be included in the base of Senator Paul’s VAT, a VAT at this rate could plausibly raise about $1.1 trillion a year.

When the dust clears, this would leave the federal government with $1.2 trillion less in tax revenue in fiscal year 2016 if the plan were implemented immediately—a reduction of about one-third in total federal revenues. Over a decade, the plan would cost a stunning $15 trillion.

Sen. Paul seems unfazed by this math, arguing that these massive tax cuts would act as “an economic steroid injection” that would make it possible to balance the federal budget—something Paul has proposed he would do as President. (If this line seems familiar to residents of Kansas, it’s because they’ve heard it from their governor repeatedly over the past four years.)

But it’s hard to see how this could be possible. Even the Tax Foundation, which he cites as providing evidence that his plan wouldn’t cost anything, finds that the Paul plan would cost $960 billion over ten years when “dynamic scoring” is factored in. And the Tax Foundation’s approach to dynamic scoring notoriously assumes that while tax cuts always spur economic growth, government spending on education, roads and health care has no positive impact on the economy at all. A more clear-eyed approach to measuring the “dynamic” effect of federal tax changes would at least attempt to quantify the very real—and very beneficial—effect of public investments on the national economy.

It should go without saying that given the fiscal challenges facing America—and given the chronic deficits Congress and the President have authorized in recent years—the most sensible first step toward sustainable tax reform should be to raise more revenue. But it seems very likely that Paul’s plan would blow a trillion-dollar hole in the federal budget each year. That’s the furthest thing from a sustainable tax plan.

South Carolina Senator Lindsey Graham, yet another

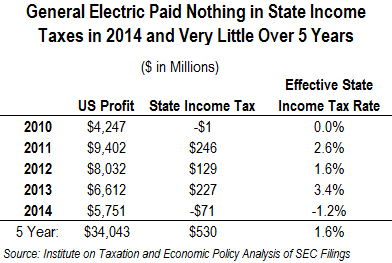

South Carolina Senator Lindsey Graham, yet another  Each year, General Electric publishes basic data on its nationwide state (and federal) income tax liabilities in its annual financial report, as required by the Securities and Exchange Commission. These reports show that the company routinely pays little or no state income tax on billions of dollars in profit nationwide:

Each year, General Electric publishes basic data on its nationwide state (and federal) income tax liabilities in its annual financial report, as required by the Securities and Exchange Commission. These reports show that the company routinely pays little or no state income tax on billions of dollars in profit nationwide: