September 11, 2014 11:18 PM | Permalink |

Read this report in PDF.

The pace of corporate inversions has increased in the last decade but only recently has this practice begun to make headlines with known American brands such as Burger King announcing plans to become foreign companies for tax purposes. A company inverts when, technically, it merges with and becomes a subsidiary of a foreign company. The practice is under fire because many American corporations undergo inversions to subsequently reduce their U.S. tax bill, either through earnings stripping to avoid U.S. taxes on future profits, or, by avoiding U.S. taxes on profits already earned and accumulated offshore.

This document focuses on the latter, tax avoidance on profits already accumulated offshore, and argues that this problem can be addressed by requiring payment of the U.S. tax that has been deferred on these offshore profits at the point when a corporation officially becomes controlled by a foreign company, whether through inversion or through other means. This reform would be akin to the requirement that individuals pay income taxes on unrealized capital gains when they renounce their U.S. citizenship.

Individuals and corporations are both allowed to defer paying U.S. taxes on key parts of their income. Under current law, wealthy individuals are required to give up this benefit when they renounce their American citizenship, while profitable corporations are not.

The tax code allows American individuals to defer paying income taxes on capital gains (appreciation of their assets) until they sell their assets. But wealthy individuals who renounce their U.S. citizenship lose this benefit and are required to pay tax on unrealized capital gains.[1]

American corporations are allowed to defer paying income taxes on profits earned by their offshore subsidiaries until those profits are brought to the U.S., but under current law are not required to give up that benefit even after being acquired by a foreign owner. This more generous treatment of corporations has no apparent rationale and seems to be an accident of history rather than the intent of Congress.

Legislative history (explained below) suggests that Congress preserved deferral to help American multinational corporations compete with foreign-based multinational corporations. There is no reason to continue this tax break for corporations once they declare that they are no longer American.

Ending deferral in this situation would also remove a significant incentive for corporations to undergo inversions and could complement other legislative proposals to prevent inversions.

This document uses the term “American corporation” or “U.S. corporation” to describe what the tax code calls a “domestic” corporation, one that is “organized in the United States or under the law of any State.”[2] A foreign corporation is one that is not domestic.[3] We use the term “offshore subsidiary” of an American corporation to describe what the tax code calls a “controlled foreign corporation,” or CFC.[4]

Deferral Facilitates Tax Avoidance

Income that is subject to the federal income tax includes dividends and other payments made from corporations.[5] That is true whether the dividend is income received by an individual or another corporation. Profits earned outside the United States by a foreign corporation are not subject to federal income tax except when those profits are paid (usually as a dividend) to a U.S. individual or domestic corporation that owns the foreign corporation.[6] This means, in effect, that a U.S. corporation is allowed to defer paying federal income tax on profits earned by foreign corporations that it owns (earned by its offshore subsidiaries) until those profits are repatriated (until they are paid to the U.S. corporation as a dividend or similar payment).

This general approach has been in place since the enactment of the federal income tax. By the 1960s, American corporations widely recognized they could simply create a shell corporation in a country with very low or no corporate tax (an offshore tax haven) and use accounting tricks to make profits earned in the United States appear to be earned in the tax haven. For example, a domestic corporation might claim that it owns a foreign corporation in a tax haven and that this tax haven corporation holds the logos used by the domestic corporation. The domestic corporation claims that it must therefore pay (to the tax haven corporation) royalties that wipe out its U.S. income for tax purposes.

In reality, the domestic corporation and the foreign corporation are owned by the same people and operate as one company, so this arrangement is a gimmick that allows tax accountants to move money between different parts of the same company. But because the IRS recognizes the corporations as separate entities, the domestic corporation can defer paying taxes on these profits indefinitely.

To address this, President Kennedy proposed ending deferral of federal corporate income tax on most profits generated by American corporations’ offshore subsidiaries in most circumstances.[7] What Congress ultimately enacted was the part of the tax code commonly referred to as subpart F, which ended deferral only for certain kinds of “passive” income (such as royalties in the example above) paid from a “controlled foreign corporation,” (CFC) which is defined as a foreign corporation that is majority owned by U.S. shareholders, including domestic corporations.[8]

There are numerous loopholes in subpart F and today it is quite clear that much of the income that U.S. corporations report as earned by their CFCs (their offshore subsidiaries) is actually income earned in the United States or another country with a normal tax system but manipulated to appear as though it is earned in offshore tax havens.[9]

Today, American multinational corporations have an estimated $2 trillion in offshore subsidiary profits that have not been repatriated to the U.S., and $1 trillion of that amount is likely in cash or cash equivalents that could fairly easily be repatriated. Because American corporations only pay U.S. income tax on these profits when they are repatriated, they have an incentive to declare them offshore “permanently reinvested earnings” rather than repatriating them to the U.S.

As discussed below, after an inversion, the corporation can route its offshore “permanently reinvested earnings” through the ostensible foreign parent company or through its subsidiaries to indirectly get the money into the hands of the U.S. shareholders without triggering the tax that is normally due upon repatriation. The simplest way to end this tax dodge is to tax these profits accumulated by offshore subsidiaries as if they had been repatriated at the point when their U.S. parent corporation inverts. This would remove much of the benefit of inversion.

Profits Held Offshore Have Not Been Taxed by the U.S. — and Will Never Be After Inversion

Domestic corporations have an incentive to not repatriate the profits of their offshore subsidiaries (profits of their CFCs). This is most true of those profits that are earned in the U.S. or another country with a normal tax system and then manipulated to appear to be earned in a tax haven. The U.S. federal income tax bill on repatriated profits is reduced by the amount of income taxes paid to foreign governments. So, profits earned in a country with a normal tax system are subject to much less than the full U.S. corporate income tax rate upon repatriation. But profits that are earned (at least officially) in a tax haven with a zero tax rate would be subject to the full U.S. statutory corporate income tax rate of 35 percent upon repatriation.

Several corporations, including Apple, Microsoft, Nike, Safeway, Wells Fargo, Citigroup and others have disclosed that if they repatriated their offshore subsidiary profits, the effective U.S. federal income tax due would be close to the full 35 percent statutory rate. This implies that they have paid little taxes to foreign governments because these profits are largely in tax havens.[10]

Some American corporations may never repatriate these offshore profits because they can access these profits indirectly. For example, to fund a share buyback last year, instead of repatriating any of its massive offshore cash holdings, Apple issued bonds at negligible interest rates made possible by its offshore cash.[11]

Nonetheless, many American multinational corporations seek ways to, in effect, move these offshore profits into the hands of shareholders without paying U.S. federal income tax that is due upon repatriation.

Subpart F includes a section designed to address this, section 956. Before section 956 was enacted in the 1960s, an American corporation could get around the tax by having an offshore subsidiary make an investment in its American operations that was not actually a dividend payment to the American parent company, and thus not considered a taxable repatriation. For example, the offshore subsidiary could lend money to, or guarantee a loan to, its American parent company in a way that has the same effect as paying a dividend to the American parent company. Section 956 was enacted to treat such investments as repatriations and to impose U.S. tax at that point.

Section 956 applies to investments made by the offshore subsidiaries in related American companies. A major problem is that 956 does not apply if the offshore subsidiaries “hopscotch” over their American parent company, investing or lending instead to a foreign company that has ostensibly acquired the American corporation after an inversion, or to other foreign companies that are subsidiaries of the foreign parent company, which can then funnel that money to the U.S. operations or shareholders of the U.S. company without triggering U.S. tax.

Proposals to Address Avoidance of Repatriation Tax After Inversion

One proposal, reported to be included in draft legislation by Rep. Sander Levin of Michigan, would amend section 956 to make it apply when the investment is done indirectly, routed through a foreign parent company after an inversion or through one of the other companies that is owned by the foreign parent company.[12] Another approach would be for the Treasury Department to issue regulations that would have the same effect, which seem to be authorized by section 956 and other parts of the tax code.[13] These approaches are described in detail in another report from Citizens for Tax Justice.[14]

One alternative that has not received much attention is the one described in this report. It would simply treat accumulated offshore profits as repatriated at the point when the American corporation is officially acquired by a foreign one. Whether this acquisition takes the form of an inversion, in which owners of the American corporation are not really giving up control, or a genuine takeover by a foreign buyer does not matter. Congress preserved deferral (despite President Kennedy’s proposal to largely end it) apparently as a way to help American multinational corporations compete with multinational corporations. There is no rationale for continuing to extend this tax break to corporations once they declare that they are no longer American.

This approach would dramatically reduce incentives for some corporations to invert. For example, the medical device maker Medtronic, which is merging with Covidien and plans to change its corporate address to Ireland, has $20.5 billion in permanently reinvested earnings offshore, and $13.9 billion of that is cash or cash equivalents (the profits the company is most likely to repatriate). Medtronic even acknowledges that if it repatriates these profits it would pay U.S. income taxes on them at an effective rate in the range of 25 to 30 percent, implying that much of the profits are in tax havens. [15] A major motivation for the inversion may be the desire to officially bring offshore cash to the United States without paying taxes.

Similarly, the pharmaceutical giant Pfizer, which attempted (and may attempt again) to obtain the U.K.-based drug maker AstraZeneca, has $69 billion in permanently reinvested earnings offshore. Given that Pfizer has 128 subsidiaries in countries characterized as tax havens by the Government Accountability Office, it would not be surprising if Pfizer has paid very little in foreign taxes on these profits.[16]

Under the reform described in this report, an inversion would cause these profits to be taxed as if they were repatriated. It is very unlikely that Pfizer and Medtronic and companies in similar situations would then pursue inversions.

[1] Section 877A of the tax code subjects individuals who expatriate to certain tax provisions if they have a net worth of over $2 million, had an average personal income tax liability over the previous five years above a certain amount ($157,000 for 2014) or failed to pay taxes during the previous five years. Even if one of these criteria is met, a large amount of capital gains income is excluded (the first $680,000 is excluded in 2014). Revenue Procedure 2013-35. http://www.irs.gov/pub/irs-drop/rp-13-35.pdf

[2] IRC sec. 7701(a)(4).

[3] IRC sec. 7701(a)(5).

[4] IRC sec. 957.

[5] IRC sec. 61.

[6] IRC sec. 11.

[7] Thomas L. Hungerford, “The Simple Fix to the Problem of How to Tax Multinational Corporations — Ending Deferral,” Economic Policy Institute, March 31, 2014. http://www.epi.org/publication/how-to-tax-multinational-corporations/#_ref5

[8] IRC sec. 957.

[9] Citizens for Tax Justice, “American Corporations Tell IRS the Majority of Their Offshore Profits Are in 12 Tax Havens,” May 27, 2014. http://ctj.org/ctjreports/2014/05/american_corporations_tell_irs_the_majority_of_their_offshore_profits_are_in_12_tax_havens.php As this report explains, the countries with zero corporate income tax rates or loopholes that facilitate massive tax avoidance are mostly countries that have little in the way of opportunities for real business activities. The figures clearly show that the profits that American corporations report to the IRS that they earn in these countries cannot possibly represent real business profits but are instead profits earned in countries with a normal tax system like the U.S. and then manipulated to appear to be earned in tax havens.

[10] Citizens for Tax Justice, “Dozens of Companies Admit Using Tax Havens,” May 19, 2014. http://ctj.org/ctjreports/2014/05/dozens_of_companies_admit_using_tax_havens.php

[11] Kitty Richards and John Craig, “Offshore Corporate Profits: The Only Thing ‘Trapped’ Is Tax Revenue,” Center for American Progress, January 9, 2014. http://www.americanprogress.org/issues/tax-reform/report/2014/01/09/81681/offshore-corporate-profits-the-only-thing-trapped-is-tax-revenue/

[12] This follows the advice of a former chief of staff to the Joint Committee on Taxation. See Edward D. Kleinbard, “’Competitiveness’ Has Nothing to Do with It,” August 5, 2014. http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2476453

[13] Stephen E. Shay, “Mr. Secretary, Take the Tax Juice Out of Corporate Inversions,” Tax Notes, July 28, 2014.

[14] Citizens for Tax Justice, “Proposals to Resolve the Crisis of Corporate Inversions,” August 21, 2014. http://ctj.org/ctjreports/2014/08/proposals_to_resolve_the_crisis_of_corporate_inversions.php

[15] Citizens for Tax Justice, “Medtronic: Still Offshoring,” June 26, 2014. http://www.taxjusticeblog.org/archive/2014/06/medtronic_still_offshoring.php

[16] Richard Phillips, Steve Wamhoff, Dan Smith, “Offshore Shell Games 2014: The Use of Offshore Tax Havens by Fortune 500 Companies,” June 2014. http://ctj.org/ctjreports/2014/06/offshore_shell_games_2014.php

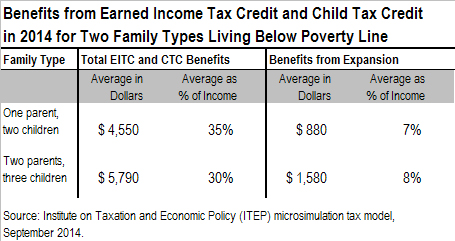

When all taxes assessed by state and local governments are taken into account, every state imposes higher effective tax rates on low-income families than the richest tax payers. On average, the lowest income households (bottom 20 percent) pay 11.1 percent of their income in state taxes, middle income households pay about 9.4 percent and the top 1 percent only pay 5.6 percent. This means state tax systems are actually making it harder for families to escape poverty.

When all taxes assessed by state and local governments are taken into account, every state imposes higher effective tax rates on low-income families than the richest tax payers. On average, the lowest income households (bottom 20 percent) pay 11.1 percent of their income in state taxes, middle income households pay about 9.4 percent and the top 1 percent only pay 5.6 percent. This means state tax systems are actually making it harder for families to escape poverty. Specifically, the report notes, “In most states, a true remedy for state tax unfairness would require comprehensive tax reform. Short of this, lawmakers should use their states’ tax systems as a means of providing affordable, effective and targeted assistance to people living in or close to poverty in their states.”

Specifically, the report notes, “In most states, a true remedy for state tax unfairness would require comprehensive tax reform. Short of this, lawmakers should use their states’ tax systems as a means of providing affordable, effective and targeted assistance to people living in or close to poverty in their states.”

Child poverty declined by 2 percent, one of the bright spots in the report. But overall, what’s most notable about the data is that the numbers aren’t shocking. Troubling? Yes. Surprising? No.

Child poverty declined by 2 percent, one of the bright spots in the report. But overall, what’s most notable about the data is that the numbers aren’t shocking. Troubling? Yes. Surprising? No.

Current Ohio Governor (and former Congressman) John Kasich (R) is running for reelection against Cuyahoga County Executive Ed Fitzgerald (D). Fitzgerald’s

Current Ohio Governor (and former Congressman) John Kasich (R) is running for reelection against Cuyahoga County Executive Ed Fitzgerald (D). Fitzgerald’s