Today the Senate Finance Committee discussed corporate inversions and other problems with the U.S. corporate tax code but showed no signs of bipartisan agreement on a solution. The hearing was held mainly to address the recent wave of corporations making bids to invert, or restructure (on paper) as foreign corporations to avoid U.S. taxes.

While committee chairman Ron Wyden (D-OR) called for immediate action from Congress to prevent corporations from avoiding taxes by inverting, the committee’s ranking Republican, Orrin Hatch, said his support was conditional on several stipulations that probably cannot be met by any reasonable legislation.

The public focus on corporate inversions began in April as the pharmaceutical giant Pfizer made a bid to merge with a smaller foreign company and then call itself a foreign corporation for tax purposes. The drug store chain Walgreens announced that it was considering doing the same. These were followed by the medical device maker Medtronic and the pharmaceutical companies Mylan and AbbVie.

Senator Wyden had previously said that Congress should enact a sweeping comprehensive tax reform that resolves all the problems with our tax code and that also has provisions addressing such inversions, which would be retroactive to May of 2014 to ensure that companies seeking to invert now are not successful in avoiding U.S. taxes. But as the number of corporations seeking inversions increased in recent weeks, Treasury Secretary Jack Lew called for immediate action. Senator Wyden is now calling for temporary legislation to address inversions until Congress can enact comprehensive tax reform.

Such legislation has been introduced in the Senate by Carl Levin (D-MI) and in the House by his brother Sander Levin, the ranking Democrat on the Ways and Means Committee.

During the hearing, Hatch said he could agree to short-term legislation to address inversions, but only if:

— it is not “punitive,” which he considers the Levin proposal to be,

— it is not retroactive,

— it is “revenue-neutral,”

— it moves the U.S. tax system closer to, rather than farther from, a “territorial” system, which would exempt the offshore profits of our corporations from U.S. taxes.

The Levin legislation that Hatch finds punitive would change the rules so that the newly restructured corporation that results from one of these mergers would be taxed as a U.S. company if it is majority-owned by the same people who owned the original U.S. corporation, or if it’s managed and controlled in the U.S. and has substantial business here. In other words, an American corporation would not be able to use a merger to undertake a “restructuring” that occurs only on paper and then claim to be a foreign company for tax purposes. This seems entirely reasonable and not punitive at all.

As for Hatch’s opposition to any retroactive change in the tax law, waiting even a couple weeks could result in more corporations that merge and claim to be foreign and able to avoid U.S. taxes forever. And a retroactive provision is not particularly burdensome for these corporations, which are on notice that such a change is likely to apply to any deals made from May on and are able to plan accordingly. In fact, Medtronic and other aspiring inverters are actually writing provisions into their merger agreements that allow them to walk away from the deals if Congress changes the rules to deny the tax benefits of inversion.

Finally, Hatch’s call to move towards a “territorial” system misses the problem completely. Hatch and many of the inverting corporations argue that companies are driven to invert because the U.S. taxes the offshore profits of American corporations when they are officially brought to the U.S. (in addition to taxing their domestic profits). Most other countries have a territorial tax system that only taxes the profits earned in that particular country. Hatch and others argue that inverting companies are trying to free their offshore profits from U.S. taxes.

There are many problems with this argument, and the biggest one is that inverting companies are trying to avoid taxes on the profits they earn here in the U.S., not just profits they earn offshore. Several witnesses at the hearing explained that after inverting, corporations typically engage in earnings stripping, which involves loading the U.S. part of the company up with debt that results in interest payments made to a foreign part of the company and interest deductions that wipe out the U.S. income for tax purposes.

For example, the manufacturer Ingersoll-Rand clearly engaged in earnings stripping after it inverted to become a Bermuda company, swiftly shifting from reporting large annual U.S. profits to reporting U.S. losses or very small profits each year along with dramatically larger offshore profits.

Some members of the Finance Committee complained that U.S. corporate tax rate is too high and that a tax reform that lowers the rate is the only answer. But it has been well-documented that the ultimate goal of much corporate tax maneuvering is to make profits appear to be earned in countries with no corporate tax at all like Bermuda, the Cayman Islands, or the British Virgin Islands. So long as loopholes remain that allow this, no reduction in the U.S. corporate tax rate can address this problem.

Comprehensive tax reform is certainly needed, but that cannot become an excuse for Congress doing nothing in the meantime to stop corporate tax avoidance schemes that will be difficult to reverse once they are in place.

Gene Simmons rocks. The front man for glam-band Kiss rocked decades ago, he rocks now, and he will continue to rock into his old age. Few Americans who came of age in the 1970s would contest this assertion.

Gene Simmons rocks. The front man for glam-band Kiss rocked decades ago, he rocks now, and he will continue to rock into his old age. Few Americans who came of age in the 1970s would contest this assertion. Odds are that a Tuesday D.C. circuit court ruling declaring health care subsidies to be illegal is not a real threat to the Affordable Care Act, but it is an important reminder about the crucial role that tax subsidies play in making health insurance more affordable for millions of Americans and the lengths that some politicians are willing to go to block them.

Odds are that a Tuesday D.C. circuit court ruling declaring health care subsidies to be illegal is not a real threat to the Affordable Care Act, but it is an important reminder about the crucial role that tax subsidies play in making health insurance more affordable for millions of Americans and the lengths that some politicians are willing to go to block them.  On Tuesday the Senate Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations

On Tuesday the Senate Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations

The gubernatorial race in Iowa pits veteran incumbent Terry Branstad (R) against challenger Jack Hatch (D). Branstad, 67, is asking Iowa voters to reelect him to an unprecedented sixth term as governor; if he wins, he will be the longest-serving governor in American history. In addition to his career in political office, Branstad has been an attorney, financial advisor, and president of Des Moines University. Hatch, 64, is a state senator from Des Moines and a former member of the Iowa House of Representatives. He is a real estate developer and businessman who founded Hatch Development Group, a company that builds affordable housing.

The gubernatorial race in Iowa pits veteran incumbent Terry Branstad (R) against challenger Jack Hatch (D). Branstad, 67, is asking Iowa voters to reelect him to an unprecedented sixth term as governor; if he wins, he will be the longest-serving governor in American history. In addition to his career in political office, Branstad has been an attorney, financial advisor, and president of Des Moines University. Hatch, 64, is a state senator from Des Moines and a former member of the Iowa House of Representatives. He is a real estate developer and businessman who founded Hatch Development Group, a company that builds affordable housing.

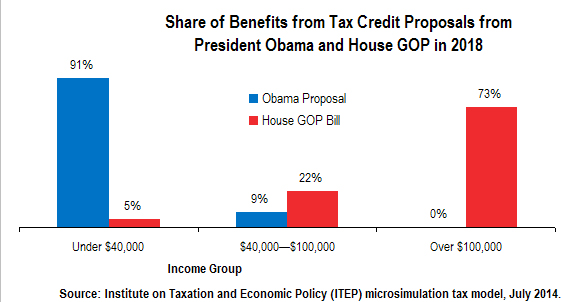

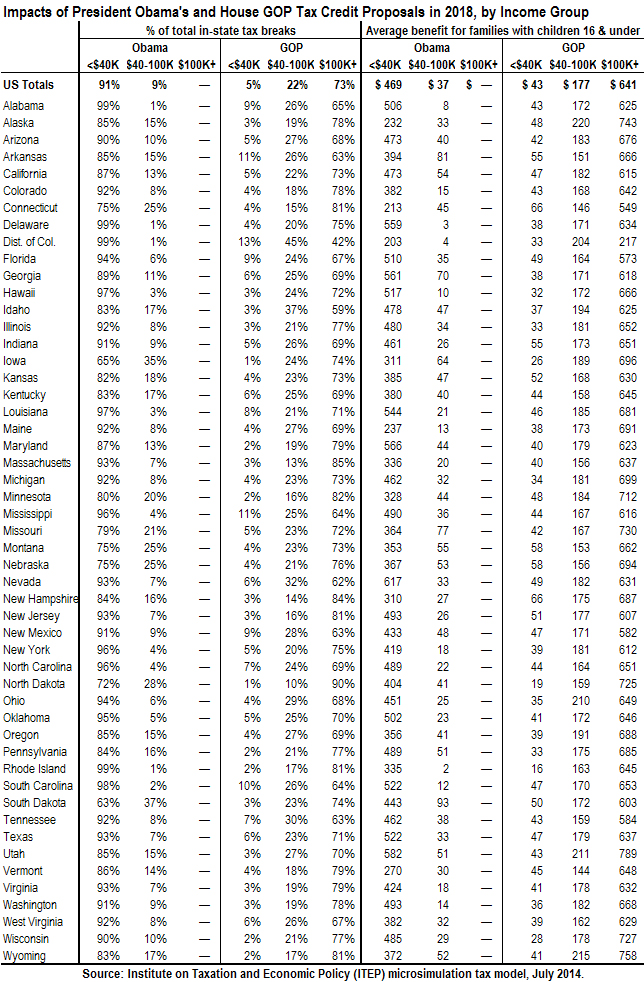

The Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy published a

The Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy published a  Abbott Labs CEO Miles White is shocked that anyone would see the recent wave of U.S. multinationals seeking to renounce their U.S. citizenship as a tax dodge.

Abbott Labs CEO Miles White is shocked that anyone would see the recent wave of U.S. multinationals seeking to renounce their U.S. citizenship as a tax dodge.