April 23, 2013 02:19 PM | Permalink |

Read this report in PDF.

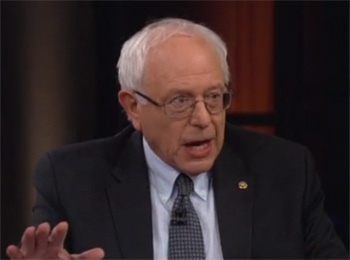

Senator Bernie Sanders of Vermont recently appeared on Real Time with Bill Maher and disputed the claim by the Tax Foundation that the U.S. has the highest corporate tax in the world.

Senator Bernie Sanders of Vermont recently appeared on Real Time with Bill Maher and disputed the claim by the Tax Foundation that the U.S. has the highest corporate tax in the world.

During a debate over spending and revenues, Senator Sanders said it’s time to ask the “one out of four corporations not paying any taxes” to contribute. The Wall Street Journal’s Stephen Moore replied with the standard complaint, “We have the highest corporate tax rate in the world. … Thirty-five percent. The Tax Foundation says the United States of America has the highest corporate tax rate.” Sanders replied that this is the “nominal, not effective” corporate tax rate.[1] The Tax Foundation then issued a written response claiming that even the effective corporate tax rate in the U.S. is very high compared to those of other countries. [2]

Senator Sanders is right, the Tax Foundation is wrong.

Effective Tax Rates vs. Nominal or Statutory Tax Rates

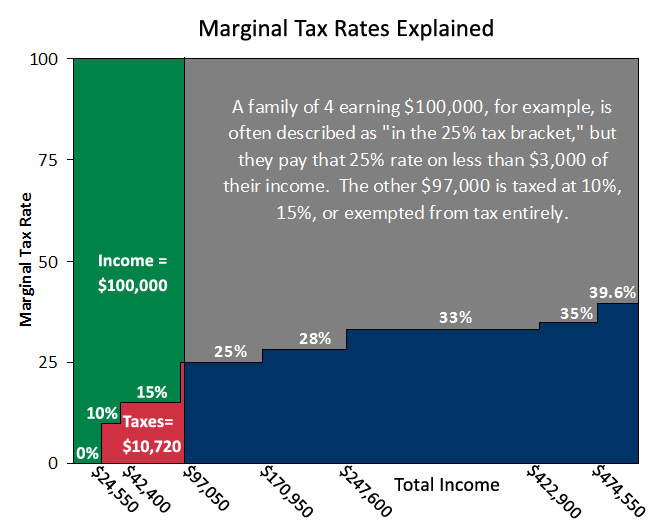

The U.S. statutory tax rate of 35 percent is almost entirely irrelevant. The effective corporate tax rate (what corporations actually pay as a percentage of their profits) is what matters, and it’s far lower than the statutory corporate tax rate because of the loopholes that allow corporations to avoid taxes. The U.S. effective corporate tax rate is also far lower than the Tax Foundation claimed in a written response to Senator Sanders.

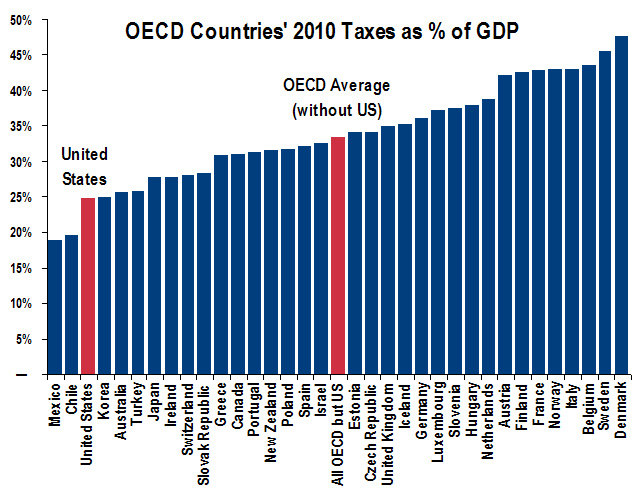

While the statutory corporate income tax rate for the U.S. may be high compared to those of other countries, the total federal corporate income tax collected in the U.S. in 2010 was equal to just 1.3 percent of our gross domestic product — in other words, 1.3 percent of our total economic output — according to the Treasury Department. The figure is 1.6 percent of GDP when state corporate income taxes are included.[3]

Data from the Organizations for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) show that the OECD countries other than the U.S. collected corporate tax revenue equal to 2.8 percent of their combined GDPs in 2010. This is another way of saying that the weighted average of corporate tax collected as a percentage of GDP for the countries that are the U.S.’s main trading partners and competitors was 2.8 percent in 2010. (2010 is the most recent year for which the OECD has complete data.)[4]

Some critics of corporate taxes claim that the declining share of the GDP paid in corporate income taxes collected in the U.S. reflects in part the growth in “pass-through” entities which are taxed only under the personal income tax and not under the corporate income tax. But almost all of the corporate income tax is paid by giant corporations, hardly any of which have shifted to pass-through status.[5]

In addition, effective corporate tax rates (on non-pass-through corporations) are very low in the United States, as CTJ has demonstrated in its comprehensive corporate tax reports.

One of the most cited of those reports was released in November of 2011 and examined most of the Fortune 500 companies that had been profitable each year over the 2008-10 period. Collectively, the companies studied paid just 18.5 percent of their profits in U.S. corporate income taxes over the three years that were studied — only half the 35 percent official corporate tax rate. Thirty of the companies paid less than nothing and had negative corporate income tax rates over that period.[6]

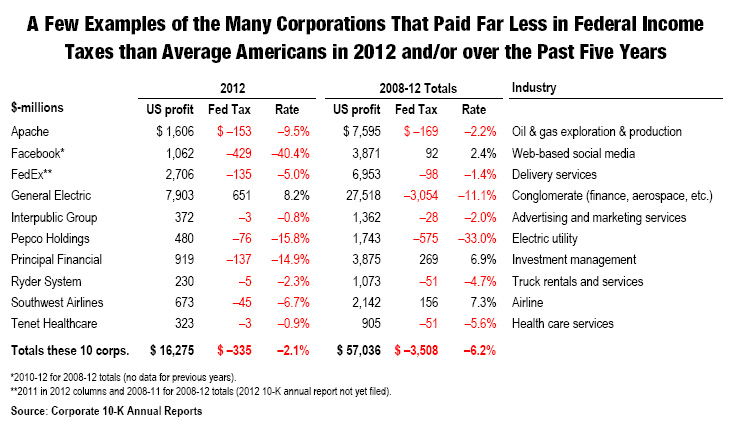

We are currently working on an update to this study, and recently released data showing ten examples of companies that paid negative or extremely low effective tax rates in 2012 and over the past five years.[7]

The Tax Foundation Relies on Flawed Research

In its written response to Senator Sanders, the Tax Foundation claims that

Even when including all deductions and credits available to companies to lower their tax liabilities, the “effective” tax rate of U.S. corporations is still among the very highest in the world. The most recent studies show a U.S. effective corporate tax rate of roughly 27 percent, compared to an average of 20 percent for other developed countries.

To back this assertion, the Tax Foundation cites its 2011 report that reviewed nine different studies of effective tax rates.[8] On close inspection of these studies, it turns out that six of them do not even examine the taxes and profits of actual firms but rather are based on models of taxation applied to hypothetical firms.

Only three of these studies are based on what the authors considered to be the actual taxes and profits paid by firms according to their financial reports. But these studies have several severe methodological problems that made it almost impossible for them to come to any conclusion other than that U.S. corporate taxes are high.

For example, one of the studies, by Kevin S. Markle and Douglas A. Shackelford of the National Bureau of Economic Research, actually states (on page 10) that it excludes those companies with a negative effective tax rate.[9] This essentially means that the study simply excludes those companies that are corporate tax dodgers, which obviously will result in a higher estimate for the average effective tax rate.

To take another example, a study by PricewaterhouseCoopers and the Business Roundtable counts what companies report in their financial filings as “deferred” taxes, as well as “current taxes” as taxes paid by a company.[10] As we have explained before, current taxes are the taxes a company actually pays during the year, while deferred taxes are the taxes that the company might pay at some point in the future (and if they ever are paid they will show up as current taxes in the financial report for that year).[11] In other words, “deferred” taxes are taxes that companies have not paid (and may never pay) and should not be counted as taxes paid.

Determining Actual Effective Corporate Tax Rates

Ultimately, the only way to understand how much corporations are actually paying in taxes is to do the painstaking work that CTJ does in going through the financial reports filed by corporations, and uncovering the hidden tax breaks that go unnoticed in the large, error-prone databases that these other studies tend to rely on.

For example, a simple reading of Facebook’s 2012 10-K annual financial report might suggest that the company pays a very large amount of federal income tax: the income tax note for the 2012 report says the company paid a current federal income tax of $559 million on its $1.062 billion in pretax US income. This implies an effective federal tax rate of 52.6%, which is a lot.

But in fact, the company reduced its federal income taxes by more than $1 billion in 2012 through the “excess stock option” tax break, the effects of which are not reported in the income tax note. Researchers using databases that simply report the contents of the income tax note will miss this essential piece of information.

The truth is that, by any measure, U.S. corporate income taxes are very low. And as a share of the economy, they are much lower than are corporate income taxes in almost every other developed country.

[1] Bud Meyers, “Bill Maher, Bernie Sanders, Makes Fool of Stephen Moore,” Daily Kos, April 12, 2013. http://www.dailykos.com/story/2013/04/12/1201358/-Bill-Maher-Bernie-Sanders-Makes-Fool-of-Stephen-Moore

[2] Richard Morrison, “Yes, Sen. Sanders, We Really Do Have the Highest Corporate Tax Rate in the World,” Tax Foundation, April 12, 2013. http://taxfoundation.org/article/yes-sen-sanders-we-really-do-have-highest-corporate-tax-rate-world

[3] In calendar 2010, the U.S. federal government collected $193.4 billion in corporate income taxes. (Monthly Treasury Statements for January 2010 to December 2010, http://www.fms.treas.gov/mts/backissues.html.) In addition, state and local governments in the U.S. collected $42.9 billion in corporate income taxes in 2010 (U.S. Census Bureau, http://www2.census.gov/govs/estimate/summary_report.pdf. Table A-1 (page 6). So total federal, state and local corporate income taxes in the U.S. in 2010 were $236.3 billion. This is 1.6 percent of U.S. GDP in 2010, which was $14.5 trillion.

[4] OECD data is available at http://stats.oecd.org/ The OECD routinely far overestimates U.S. corporate taxes as a percentage of GDP, and we have corrected OECD’s error. For some reason, the OECD gets its U.S. corporate tax information from U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA), which includes profits of the Federal Reserve as “corporate taxes.” Historically, this has caused OECD to overstate U.S. corporate income taxes by about 10 percent. But Federal Reserve profits have ballooned in recent years, causing OECD to overstate U.S. corporate income taxes by 23 percent in 2009 and 32 percent in 2010. In addition, the OECD initially publishes preliminary data from the BEA, which includes corporate taxes paid by U.S. corporations to foreign governments (an error which OECD later corrects when BEA releases final data). Because of these two errors, OECD currently overstates U.S. federal, state and local corporate by almost two-thirds in 2010.

[5] The U.S. corporate income tax has always been paid by a relatively small number of companies that has not changed very much over time. IRS data show that in 1995, 6,258 companies (which had assets of at least $250 million that year) paid 78 percent of the corporate income tax collected during that year. In 2008, a similar number of companies, 6,584 companies (which had assets of at least $500 million that year) paid 82 percent of the corporate income tax collected during that year.

[6] Citizens for Tax Justice, “Corporate Taxpayers and Corporate Tax Dodgers: 2008-2010,” November 3, 2011. http://ctj.org/corporatetaxdodgers/

[7] Citizens for Tax Justice, “Ten (of Many) Reasons Why We Need Corporate Tax Reform,” April 10, 2013. http://ctj.org/ctjreports/2013/04/ten_of_many_reasons_why_we_need_corporate_tax_reform.php

[8] Philip Dittmer, “U.S. Corporations Suffer High Effective Tax Rates by International Standards,” Tax Foundation, September 2011. http://taxfoundation.org/sites/taxfoundation.org/files/docs/sr195.pdf

[9] Kevin S. Markle and Douglas A. Shackelford, “Cross-Country Comparisons of Corporate Income Taxes,” National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper No. 16839, February 2011, http://www.nber.org/papers/w16839.pdf.

[10] “Global Effective Tax Rates,” PricewaterhouseCoopers and Business Roundtable, April 14, 2011, http://businessroundtable.org/studies-and-reports/global-effective-tax-rates/.

[11] Citizens for Tax Justice, “GE Tries to Change the Subject,” February 29, 2012. http://ctj.org/ctjreports/2012/02/ge_tries_to_change_the_subject.php

Senator Bernie Sanders of Vermont recently appeared on Real Time with Bill Maher and disputed the claim by the Tax Foundation that the U.S. has the highest corporate tax in the world.

Senator Bernie Sanders of Vermont recently appeared on Real Time with Bill Maher and disputed the claim by the Tax Foundation that the U.S. has the highest corporate tax in the world.

The Indiana Senate

The Indiana Senate  North Carolina: Russell the Public Investment Hound was back and starring in a new film,

North Carolina: Russell the Public Investment Hound was back and starring in a new film,