March 29, 2013 01:33 PM | Permalink | ![]()

The Deduction for State and Local Taxes Tops the List of Items Obama Would Limit

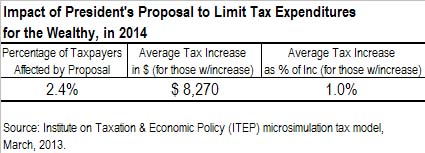

President Obama has proposed to limit the tax savings for wealthy taxpayers from itemized deductions and certain other deductions and exclusions to 28 cents for each dollar deducted or excluded. This proposal would raise more than half a trillion dollars in revenue over the upcoming decade.[1] Despite this large revenue gain, only 2.4 percent of Americans would receive a tax increase under the plan in 2014, and their average tax increase would equal just 1 percent of their income.

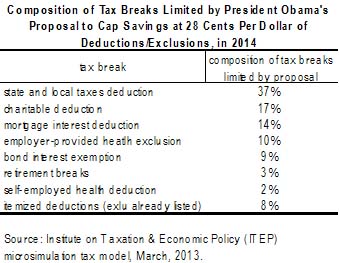

The deduction for state and local taxes would make up over a third of the total tax expenditures limited by the proposal. In combination, the deduction for state and local taxes and the deduction for charitable giving would make up more than half of the tax expenditures limited.

The proposal would apply only to taxpayers with adjusted gross income (AGI) above $250,000 for married couples and above $200,000 for singles.

The proposal is a way of limiting tax expenditures for the wealthy. The term “tax expenditures” refers to provisions that are government subsidies provided through the tax code. They have the same effect as direct spending subsidies (because the Treasury ends up with less revenue and some individual or group receives money) but are sometimes less noticed because they’re implemented through the tax code.

Under current law, there are three income tax brackets with rates higher than 28 percent (the 33, 35, and 39.6 percent brackets). People in these tax brackets could therefore lose some tax breaks under the proposal. (Some people with AGI below $250,000/$200,000 could be in the 33 percent tax bracket but would be exempt from the proposal.)[2]

Currently, a high-income person in the 39.6 percent income tax bracket saves almost 40 cents for each dollar of deductions or exclusions. An individual in the 35 percent income tax bracket saves 35 cents for each dollar of deductions or exclusions, and a person in the 33 percent bracket saves 33 cents. The lower tax rates are 28 percent or less. Many middle-income people are in the 15 percent tax bracket and therefore save only 15 cents for each dollar of deductions or exclusions.

This matters because tax deductions and exclusions are types of tax expenditures used by Congress to subsidize certain activities, like giving to charity, borrowing to buy a home, or buying bonds from state and local governments. If Congress provided such subsidies through direct spending, there would likely be a public outcry over the fact that rich people are subsidized at higher rates than low- and middle-income people. But because these subsidies are provided through the tax code, this fact has largely escaped the public’s attention.

President Obama initially presented his proposal to limit tax expenditures in his first budget plan in 2009, and included it in subsequent budget and deficit-reduction plans each year after that. The original proposal applied only to itemized deductions. The President later expanded the proposal to limit the value of certain “above-the-line” deductions (which can be claimed by taxpayers who do not itemize) like the deduction for health insurance for the self-employed and the deduction for contributions to individual retirement accounts (IRA). [3]

The proposal was also expanded to include certain tax exclusions, like the exclusion for interest on state and local bonds and the exclusion for employer-provided health care. Exclusions provide the same sort of benefit as deductions, the only difference being that they are not counted as part of a taxpayer’s income in the first place (and therefore do not need to be deducted).

Exempting the Charitable Deduction from the Limit Would Reduce the Revenue Impact by 19 Percent

Any proposal to limit tax expenditures gives rise to a debate about which tax expenditures should be subject to such a limit and which should be exempt. For example, some charities have objected to the limit applying to the deduction for charitable giving, on the mistaken view that limiting this deduction would significantly reduce charitable giving.[4]

Excluding a tax expenditure from the proposed limit may reduce the revenue impact of the proposal slightly more than or less than the corresponding percentage in the table on the first page.

For example, while the table on the first page illustrates that the charitable deduction makes up 17 percent of the tax breaks that would be limited under the President’s proposal, exempting the charitable deduction from the limit would actually reduce the revenue impact by 19 percent. While the table on the first page illustrates that the deduction for state and local taxes makes up 37 percent of the total tax breaks limited by the proposal, exempting this deduction from the limit would reduce the revenue impact of the proposal by 34 percent. The reason for these slight differences has to do with interaction between various tax provisions.

Exempting the Charitable Deduction from the Proposed Limit would Largely Turn the Remaining Proposal into a Limit on the Deduction for State and Local Taxes

Some tax-exempt organizations, particularly universities and museums, have expressed fear that the limitation on the charitable deduction will result in less charitable giving. Research suggests this fear is unfounded.[5] But another point that has received little attention is that amending the President’s proposal to “carve out” the charitable deduction would concentrate the effects of the proposal even more on the deduction for state and local taxes — which is the most justifiable of all the tax breaks the President proposes to limit.

The deduction for state and local taxes paid is sometimes seen as a subsidy for state and local governments because it effectively transfers the cost of some state and local taxes away from the residents who directly pay them and onto the federal government. For example, if a state imposes a higher income tax rate on residents who are in the 39.6 percent federal income tax bracket, that means that each dollar of additional state income taxes could reduce federal income taxes on these high-income residents by almost 40 cents. The state government may thus be more willing to enact the tax increase because its high-income residents will really only pay 60 percent of the tax increase, while the federal government will effectively pay the remaining 39.6 percent.

But viewed a different way, the deduction for state and local taxes is not a tax expenditure at all, but instead is a way to define the amount of income a taxpayer has available to pay federal income taxes. State and local taxes are an expense that reduces one’s ability to pay federal income taxes in a way that is generally out of the control of the taxpayer. A taxpayer in a high-tax state has less income to pay federal income taxes than a taxpayer with the same pre-tax income but residing in a low-tax state.

Another argument in favor of the itemized deduction for state and local taxes paid is that the public investments funded by state and local taxes produce benefits for the entire nation. This can be seen as a justification for the deduction for state and local taxes paid because it encourages state and local governments to raise the tax revenue to fund these public investments that the jurisdictions might otherwise not make.

For example, state and local governments provide roads that, in addition to serving local residents, facilitate interstate commerce. State and local governments also provide education to those who may leave the jurisdiction and boost the skill level of the nation as a whole, boosting the productivity of the national economy. State and local governments may have an incentive to provide less of these public investments than is optimal for the nation because the benefits partly go to those outside the jurisdiction. The deduction for state and local taxes may counter this inclination of state and local governments to under-invest in these areas.

[1] A recent CTJ report explains that the Treasury is likely to estimate that the President’s proposal to limit tax expenditures for the wealthy would raise $583 billion over a decade while the Congressional Joint Committee on Taxation (JCT) is likely to estimate that it will raise $513 billion over a decade. See Citizens for Tax Justice, “Working Paper on Tax Reform Options: End Tax Sheltering of Investment Income and Corporate Profits and Limit Tax Breaks for the Wealthy,” February 4, 2013. http://ctj.org/ctjreports/2013/02/working_paper_on_tax_reform_options.php

[2] Many of the wealthy taxpayers whose deductions and exclusions are targeted by the proposal would also experience a change in their alternative minimum tax (AMT). The AMT is a backstop tax, meaning it forces well-off people who effectively reduce their taxable income with various deductions and exclusions to pay some minimal tax. If a tax change only increases the regular income tax and not the AMT, some taxpayers who currently pay AMT will not be affected at all. Very generally, one of the AMT changes in the proposal essentially ensures that the increase in a taxpayer’s regular income tax would also be applied to the AMT to ensure that the tax increase shows up on the final income tax bill. The other AMT change would limit the savings for each dollar of deductions or exclusions to 28 cents for those whose income is within the “phase-out range” for the exemption that prevents most people from being affected by the AMT. The impacts of these changes are included in the estimates shown here.

[3] The most recent description of the proposal provided by the Obama administration can be found in Department of the Treasury, “General Explanations of the Administration’s Fiscal Year 2013 Revenue Proposals,” February 2012, page 73. http://www.treasury.gov/resource-center/tax-policy/Pages/general_explanation.aspx

[4] For example, see Joseph Cordes, “Effects of Limiting Charitable Deductions on Nonprofit Finances,” presentation given February 28, 2013 at the Urban Institute. Cordes finds that the President’s proposal to limit the tax savings of each dollars of deductions and exclusions to just 28 cents would reduce charitable giving by individuals by between 2.1 percent and 4.1 percent, and the actual loss of total charitable giving would be smaller because some charitable contributions are made by foundations, corporations and other entities rather than individuals affected by this proposal. http://www.urban.org/taxandcharities/upload/cordesv5.pdf

[5] Id.

Texas and Washington State are continuing to search for ways to make it easier to identify and repeal tax breaks that aren’t worth their cost. The Texas Austin American-Statesman

Texas and Washington State are continuing to search for ways to make it easier to identify and repeal tax breaks that aren’t worth their cost. The Texas Austin American-Statesman

Actor John Cleese, most famous for his central role in the British comedy group Monty Python, has decided

Actor John Cleese, most famous for his central role in the British comedy group Monty Python, has decided  New Mexico lawmakers recently approved a cut in the corporate income tax rate and special tax breaks for manufacturers and filmmakers. State officials estimate that the bill

New Mexico lawmakers recently approved a cut in the corporate income tax rate and special tax breaks for manufacturers and filmmakers. State officials estimate that the bill

of the corporations that is a member of the RATE Coalition, paid nothing in net federal income taxes from 2002 through 2011, despite $32 billion in pre-tax U.S. profits. In fact, Boeing has actually reported more than $2 billion in negative total federal taxes over that period.

of the corporations that is a member of the RATE Coalition, paid nothing in net federal income taxes from 2002 through 2011, despite $32 billion in pre-tax U.S. profits. In fact, Boeing has actually reported more than $2 billion in negative total federal taxes over that period.