May 15, 2014 04:38 PM | Permalink | ![]()

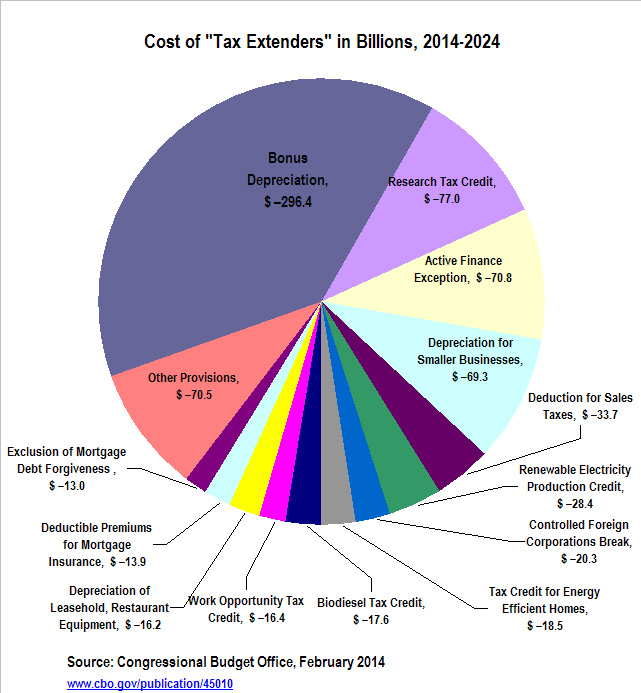

The Senate is likely to approve a bill often called the “tax extenders” because it would extend dozens of tax breaks, mostly benefiting corporations and other businesses, for two years. This bill would increase the deficit by $85 billion over the coming decade, but the number everyone should be concerned with is much bigger — over $700 billion. That’s the increase in the deficit that would result if Congress stays on its current course of extending these tax breaks every two years over the coming decade. The Senate has given every indication that this is the direction it’s headed in.

One problem is that lawmakers are willing to increase the deficit in order to hand out tax subsidies like the tax extenders to corporations and other businesses, even while they insist that any benefits for working families or the unemployed must be somehow paid for in order to avoid an increase in the deficit. Another problem is that most of the tax cuts that are part of the tax extenders are themselves bad policy. Both of these problems could be solved, or at least mitigated, by amending the legislation to include various loophole-closing provisions and reforms that are described in this report.

I. Congressional Hypocrisy in Insisting on Offsetting the Cost of Helping Working Families, but Increasing the Deficit to Help Corporations and Other Businesses

If lawmakers insist that the cost of any assistance for low- and middle-income working families must be offset to avoid an increase in the deficit, then it would be reasonable for lawmakers to offset the cost of any legislation providing business tax breaks by closing existing tax loopholes that businesses enjoy. Unfortunately, that’s not the approach Congress has taken.

In the past several months, Congress made clear that it will not enact an extension of emergency unemployment benefits (which have never been allowed to expire while the unemployment rate was as high as today’s level) unless the costs are offset to prevent an increase in the budget deficit.[1] The bill approved by the Senate earlier this year to extend those benefits through May included provisions to offset the cost, which is $10 billion.

Congress has also, in the last several years, enacted automatic spending cuts of about $109 billion a year known as “sequestration” in order to address an alleged budget crisis. Even popular public investments like Head Start and medical research were slashed. The chairman of the House and Senate Budget Committees (Republican Paul Ryan and Democrat Patty Murray) struck a deal in December that undoes some of that damage but leaves in place most of the sequestration for 2014 and barely touches it in 2015.[2]

Meanwhile, lawmakers have expressed almost no concern that the “tax extenders” are enacted every two years without any provisions to offset the costs. According to figures from the Congressional Budget Office, if Congress continues to extend these breaks every couple years, they will reduce revenue more than $700 billion over a decade.[3]

II. The Tax Extenders Are Mostly Bad Policy

Often a lawmaker or a special interest group will argue that the tax extender legislation should be enacted because it includes some provision that seems well-intentioned but makes up only a tiny fraction of the cost of the overall package of tax breaks.

For example, some support the deduction for teachers who purchase classroom supplies out of their own pockets. Never mind that this provides a tiny benefit that hardly excuses the absurdity that teachers are forced to purchase school supplies with their own money. (A school teacher in the 15 percent income tax bracket saves less than $40 a year under this provision). The important point is that this break makes up just 0.3 percent of the cost of the tax extenders package. This meager provision that supposedly helps teachers cannot possibly be the justification for enacting over $700 billion worth of tax cuts that mostly go to corporations and businesses.

The same is true for other provisions included among the tax extenders that are often cited as important benefits for ordinary Americans. One provision often cited is the exclusion of mortgage debt forgiveness from taxable income. Regardless of what one thinks about this policy, it cannot possibly justify enacting the entire package of provisions, given that it makes up just two percent of the costs.

The most costly three provisions among the tax extenders — bonus depreciation, the research credit, and the so-called “active financing exception” — make up 58 percent of the total cost of the package and yet do not seem to be designed to actually help the economy, as discussed below. The fourth most costly break, small business expensing, is unlikely to boost small businesses in the way that its proponents claim, although at least very large companies are restricted from using it. The fifth most costly provision is the deduction for state and local sales taxes, which supposedly is important to the nine states that do not have state income taxes, meaning their residents get no advantage from the existing federal deduction for state income taxes. But the reality is that most of the residents in those states do not benefit. Many of the other tax extenders are either poor policy or subsidies that could more sensibly be provided through direct spending.

It would be difficult for anyone (particularly a member of Congress) to understand all of the provisions, which number over 50. Below is a description of the most significant provisions which make up the vast majority of the cost of the legislation.

Bonus Depreciation

$296.4 billion

Bonus depreciation is a significant expansion of existing breaks for business investment. Unfortunately, Congress does not seem to understand that business people make decisions about investing and expanding their operations based on whether or not there are customers who want to buy whatever product or service they provide. A tax break subsidizing investment will benefit those businesses that would have invested anyway but is unlikely to result in much, if any, new investment.

Companies are allowed to deduct from their taxable income the expenses of running the business, so that what’s taxed is net profit. Businesses can also deduct the costs of purchases of machinery, software, buildings and so forth, but since these capital investments don’t lose value right away, these deductions are taken over time. In other words, capital expenses (expenditures to acquire assets that generate income over a long period of time) usually must be deducted over a number of years to reflect their ongoing usefulness.

In most cases firms would rather deduct capital expenses right away rather than delaying those deductions, because of the time value of money, i.e., the fact that a given amount of money is worth more today than the same amount of money will be worth if it is received later. For example, $100 invested now at a 7 percent return will grow to $200 in ten years.

Bonus depreciation is a temporary expansion of the existing breaks that allow businesses to deduct these costs more quickly than is warranted by the equipment’s loss of value or any other economic rationale.

A report from the Congressional Research Service reviews efforts to quantify the impact of bonus depreciation and explains that “the studies concluded that accelerated depreciation in general is a relatively ineffective tool for stimulating the economy.”[4]

Research Tax Credit

$77 billion

A report from Citizens for Tax Justice explains that the research credit needs to be reformed dramatically or allowed to expire.[5] One aspect of the credit that needs to be reformed is the definition of research. As it stands now, accounting firms are helping companies obtain the credit to subsidize redesigning food packaging and other activities that most Americans would see no reason to subsidize. The uncertainty about what qualifies as eligible research also results in substantial litigation and seems to encourage companies to push the boundaries of the law and often cross them.

Another aspect of the credit that needs to be reformed is the rules governing how and when firms obtain the credit. For example, Congress should bar taxpayers from claiming the credit on amended returns, because the credit cannot possibly be said to encourage research if the claimant did not even know about the credit until after the research was conducted.

As it stands now, some major accounting firms approach businesses and tell them that they can identify activities the companies carried out in the past that qualify for the research credit, and then help the companies claim the credit on amended tax returns. When used this way, the credit obviously does not accomplish the goal of increasing the amount of research conducted by businesses.

Active Financing Exception (aka GE Loophole)

$70.8 Billion

“Subpart F” of the tax code attempts to bar American corporations from “deferring” (delaying) paying U.S. taxes on certain types of offshore profits that are easily shifted out of the United States, such as interest income. The “active financing” exception to subpart F allows American corporations to defer paying taxes on offshore income even though such income is often really earned in the U.S. or other developed countries, but has been artificially shifted into an offshore tax haven in order to avoid taxes.

The “active financing” exception should never be a part of the tax code.

The U.S. technically taxes the worldwide corporate profits, but American corporations can “defer” (delay indefinitely) paying U.S. taxes on “active” profits of their offshore subsidiaries until those profits are officially brought to the U.S. “Active” profits are what most ordinary people would think of as profits earned directly from providing goods or services.

“Passive” profits, in contrast, include dividends, rents, royalties, interest and other types of income that are easier to shift from one subsidiary to another. Subpart F tries to bar deferral of taxes on such kinds of offshore income. The so-called “active financing exception” makes an exception to this rule for profits generated by offshore financial subsidiaries doing business with offshore customers.

The active financing exception was repealed in the loophole-closing1986 Tax Reform Act, but was reinstated in 1997 as a “temporary” measure after fierce lobbying by multinational corporations. President Clinton tried to kill the provision with a line-item veto; however, the Supreme Court ruled the line-item veto unconstitutional and reinstated the exception. In 1998 it was expanded to include foreign captive insurance subsidiaries. It has been extended numerous times since 1998, usually for only one or two years at a time, as part of the tax extenders.

As explained in a report from Citizens for Tax Justice, the active financing exception provides a tax advantage for expanding operations abroad. It also allows multinational corporations to avoid tax on their worldwide income by creating “captive” foreign financing and insurance subsidiaries.[6] The financial products of these subsidiaries, in addition to being highly fungible and highly mobile, are also highly susceptible to manipulation or “financial engineering,” allowing companies to manipulate their tax bill as well.

As the report explains, the exception is one of the reasons General Electric paid, on average, only a 1.8 percent effective U.S. federal income tax rate over ten years. G.E.’s federal tax bill is lowered dramatically with the use of the active financing exception provision by its subsidiary, G.E. Capital, which Forbes noted has an “uncanny ability to lose lots of money in the U.S. and make lots of money overseas.”[7]

Section 179 Small Business Expensing

$69.3 billion

Congress has showered businesses with several types of depreciation breaks, that is, breaks allowing firms to deduct the cost of acquiring or developing a capital asset more quickly than that asset actually wears out. There are massive accelerated depreciation breaks that are a permanent part of the tax code as well as many that are (at least officially) temporary, like bonus depreciation (which has already been described) and section 179. Section 179 allows smaller businesses to write off most of their capital investments immediately (up to certain limits).

A report from the Congressional Research Service reviews efforts to quantify the impact of depreciation breaks and explains that “the studies concluded that accelerated depreciation in general is a relatively ineffective tool for stimulating the economy.”[8]

One positive thing that can be said about section 179 is that it is more targeted towards small business investment than any of the other tax breaks that are alleged to help small businesses.

Section 179 allows firms to deduct the entire cost of a capital purchase (to “expense” the cost of a capital purchase) up to a limit. The most recent tax extenders package included provisions that allowed expensing of up to $500,000 of purchases of certain capital investments (generally, equipment but not land or buildings). The deduction is reduced a dollar for each dollar of capital purchases exceeding $2 million, and the total amount expensed cannot exceed the business income of the taxpayer.

These limits mean that section 179 generally does not benefit large corporations like General Electric or Boeing, even if the actual beneficiaries are not necessarily what ordinary people think of as “small businesses.”

There is little reason to believe that business owners, big or small, respond to anything other than demand for their products and services. But to the extent that a tax break could possibly prod small businesses to invest, section 179 is somewhat targeted to accomplish that goal.

Deduction for State and Local Sales Taxes

$33.7 billion

Permanent provisions in the federal personal income tax allow taxpayers to claim itemized deductions for property taxes and income taxes paid to state and local governments. Long ago, a deduction was allowed for state and local sales taxes, but that was repealed as part of the 1986 tax reform. In 2004, the deduction for sales taxes was brought back temporarily and extended several times since then.

Because the deduction for state and local sales taxes cannot be taken along with the deduction for state and local income taxes, in most cases, taxpayers will take the sales tax deduction only if they live in one of the handful of states that have no state income tax.

Taxpayers can keep their receipts to substantiate the amount of sales taxes paid throughout the year, but in practice most people use rough calculations provided by the IRS for their state and income level. People who make a large purchase, such as a vehicle or boat, can add the tax on such purchases to the IRS calculated amount.

There are currently nine states that have no broad-based personal income tax and rely more on sales taxes to fund public services. Politicians from these states argue that it’s unfair for the federal government to allow a deduction for state income taxes, but not for sales taxes. But this misses the larger point. Sales taxes are inherently regressive and this deduction cannot remedy that since it is itself regressive.

To be sure, lower-income people pay a much higher percentage of their incomes in sales taxes than the wealthy. But lower-income people also are unlikely to itemize deductions and are thus less likely to enjoy this tax break. In fact, the higher your income, the more the deduction is worth, since the amount of tax savings depends on your tax bracket.

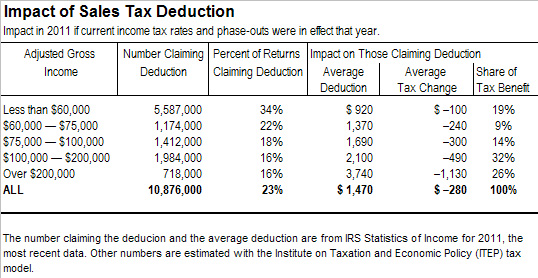

The table above includes taxpayer data from the IRS for 2011, the most recent year available, along with data generated from the Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy (ITEP) tax model to determine how different income groups would be affected by the deduction for sales taxes in the context of the federal income tax laws in effect today.

As illustrated in the table, people making less than $60,000 a year who take the sales-tax deduction receive an average tax break of just $100, and receive less than a fifth of the total tax benefit. Those with incomes between $100,000 and $200,000 enjoy a break of almost $500 and receive a third of the deduction, while those with incomes exceeding $200,000 save $1,130 and receive just over a fourth of the total tax benefit.

Renewable Electricity Production Tax Credit

$28.4 billion

The renewable electricity production tax credit (PTC) subsidizes the generation of electricity from wind and other renewable sources. The credit is 2.3 cents per kilowatt for electricity generated from wind turbines and less for energy produced by other types of renewable sources.

First created in 1992, the PTC is one tax extender that may actually expire. It has been criticized by many conservative lawmakers and organizations that tend to not object to other tax extenders, perhaps because they see wind energy as a competitor to fossil fuels.[9]

Unlike most other tax extenders, the PTC was last extended for only one year. However, the cost estimate for the PTC was larger than usual at that time because that law also expanded the PTC by allowing wind turbines (and other such facilities) to qualify so long as their construction began during 2013, whereas before the turbines had to be up and running by the end of the year.

Controlled Foreign Corporations Look-Through Rule (aka Apple Loophole)

$20.3 billion

Another exception to the general Subpart F rules requiring current taxation of passive income, the “CFC look-thru rules” allow a U.S. multinational corporation to defer tax on passive income, such as royalties, earned by a foreign subsidiary (a “controlled foreign corporation” or “CFC”) if the royalties are paid to that subsidiary by a related CFC and can be traced to the active income of the payer CFC.[10]

The closely watched Apple investigation by the Senate Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations a year ago resulted in a memorandum — signed by the subcommittee’s chairman and ranking member, Carl Levin and John McCain — that listed the CFC look-through rule as one of the loopholes used by Apple to shift profits abroad and avoid U.S. taxes.[11]

Tax Credit for Residential Energy Efficiency

$18.5 billion

The section 25C tax credit for energy improvements is capped at $500 and can go towards the costs of improving doors, windows, insulation, roofing or other improvements that make a home more energy efficient. While this is a perfectly reasonable role for the federal government to play, there is no obvious reason why it is best carried out through the tax code.

Work Opportunity Tax Credit

$16.4 billion

The Work Opportunity Tax Credit ostensibly helps businesses hire welfare recipients and other disadvantaged individuals. But a report from the Center for Law and Social Policy concludes that it mainly provides a tax break to businesses for hiring they would have done anyway:[12]

WOTC is not designed to promote net job creation, and there is no evidence that it does so. The program is designed to encourage employers to increase hiring of members of certain disadvantaged groups, but studies have found that it has little effect on hiring choices or retention; it may have modest positive effects on the earnings of qualifying workers at participating firms. Most of the benefit of the credit appears to go to large firms in high turnover, low-wage industries, many of whom use intermediaries to identify eligible workers and complete required paperwork. These findings suggest very high levels of windfall costs, in which employers receive the tax credit for hiring workers whom they would have hired in the absence of the credit.

15-Year Cost Recovery Break for Leasehold, Restaurants, and Retail

$16.2 billion

As already explained, Congress has showered all sorts of businesses with breaks that allow them to deduct the cost of developing capital assets more quickly than they actually wear out. This particular tax extender allows certain businesses to write off the cost of improvements made to restaurants and stores over 15 years rather than the 39 years that would normally be required.

It is unclear why helping restaurant owners and store owners improve their properties should be seen as more important than nutrition and education for low-income children or unemployment assistance or any of the other benefits that lawmakers insist cannot be enacted if they increase the deficit.

Deduction for Tuition and Related Expenses

$2.4 billion

The deduction for tuition and related expenses is not among the larger tax extenders, but it’s worth understanding because it is one of the provisions that lawmakers sometimes cite a reason to support the tax extenders legislation. Given that this deduction makes up only 0.3 percent of the cost of the entire tax extenders legislation, it cannot possibly be justification for supporting the legislation.

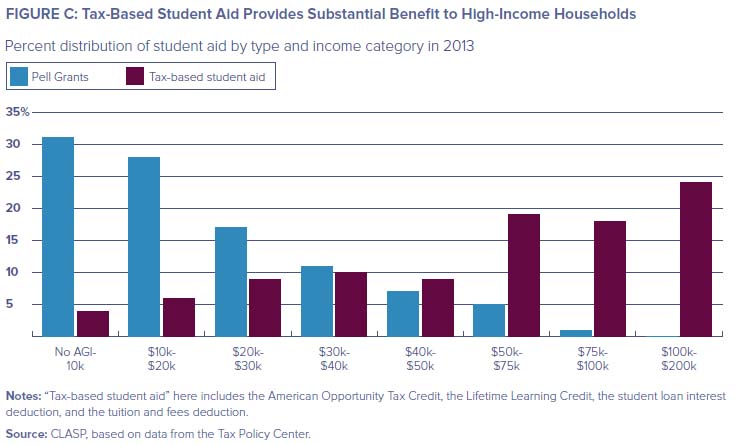

The deduction for tuition and related expenses is also bad policy. It is the most regressive tax break for postsecondary education. The distribution of tax breaks for postsecondary education among income groups is important because if their purpose is to encourage people to obtain education, they will be more effective if they are targeted to lower-income households that could not otherwise afford college rather than well-off families that will send their kids to college no matter what.

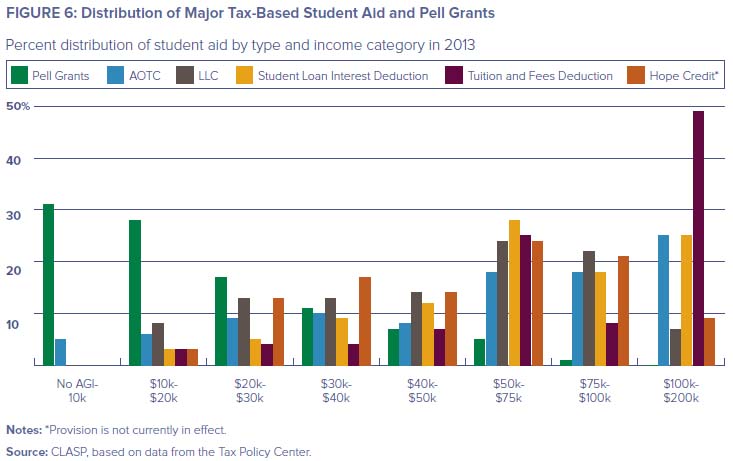

The graph below was produced by the Center for Law and Social Policy (CLASP) using data from the Tax Policy Center, and compares the distribution of various tax breaks for postsecondary education as well as Pell Grants.

The graph illustrates that not all tax breaks for postsecondary education are the same, and the deduction for tuition and related expenses is the most regressive of the bunch. Some of these tax breaks are more targeted to those who really need them, although none are nearly as well-targeted to low-income households as Pell Grants. Tax cuts for higher education taken together are not well-targeted, as illustrated in the bar graph below.

Americans paying for undergraduate education for themselves or their kids in 2009 or later generally have no reason to use the deduction because starting that year another break for postsecondary education was expanded and became more advantageous. The more advantageous tax break is the American Opportunity Tax Credit (AOTC), which has a maximum value of $2,500. The deduction for tuition and related expenses, in contrast, can be taken for a maximum of $4,000, and since it’s a deduction that means the actual tax savings for someone in the 25 percent income tax bracket cannot be more than $1000.

The AOTC is more generous across the board. Under current law, the AOTC is phased out for married couples with incomes between $160,000 and $180,000, whereas the deduction for tuition and related expenses is phased out for couples with incomes between $130,000 and $160,000. For moderate-income families, the AOTC is more beneficial because it is a credit rather than a deduction. The working families who pay payroll and other taxes but earn too little to owe federal income taxes — meaning they cannot use many tax credits — benefit from the AOTC’s partial refundability (up to $1,000).

Given that a taxpayer cannot take both the AOTC and the deduction, why would anyone ever take the deduction? The AOTC is available only for four years, which means it would normally be used for undergraduate education, while the deduction could be used for graduate education or in situations in which undergraduate education takes longer than four years. The deduction can also be used for students who enroll for only a class or two, while the AOTC is also only available to students enrolled at least half-time for an academic period during the year.

Even for graduate students and others in extended education, under current law the Lifetime Learning Credit (LLC) is generally a better deal than the tuition and expenses deduction. Because the upper income limit for the LLC is lower — $124,000 if married, $62,000 if single, the tuition and expenses deduction primarily benefits taxpayers paying for graduate school or other lifetime learning whose income is above these thresholds.

III. How the Tax Extenders Bill Could Be Made Tolerable with Amendments

In a rational world, lawmakers who feel compelled to enact the tax extenders would at least amend the legislation to offset the cost and make some of the tax policies more effective or less harmful to the U.S. economy.

Some potential amendments would mainly accomplish the first goal, offsetting the costs of the tax extenders, without affecting the operation of the tax extenders provisions themselves. Other potential amendments would improve or mitigate the tax extenders themselves.

Example of Amendments that Would Offset Cost of Tax Extenders

The following example describes three proposals from the president’s budget that would crack down on offshore tax avoidance by corporations and would, combined, raise nearly $80 billion over a decade, which is almost enough to offset the $85 billion cost of the Senate’s legislation to extend the package of tax breaks for two years.[13]

One obvious place to start closing corporate tax loopholes would be to enact the President’s proposal to crack down on corporate “inversions,” in which an American corporation reincorporates itself as a “foreign” company, without changing much about where it actually does business, simply to avoid U.S. taxes. This is likely on lawmakers’ minds because of news that inversions may be pursued by the pharmaceutical giant Pfizer and the drug store chain Walgreen Co.[14]

A loophole in current law allows the entity resulting from the merger of a U.S. corporation and a foreign corporation to be considered a “foreign” company even if it is 80 percent owned by shareholders of the American corporation, and even if most of the business activity and headquarters of the resulting entity are in the U.S. The President’s proposal would treat the resulting entity as a U.S. corporation for tax purposes if the majority (rather than over 80 percent) of the ownership is unchanged or if it has substantial business in the U.S. and is managed in this country. The president’s proposal is projected to raise $17.3 billion over a decade.

Another proposal in the president’s budget would address “earnings-stripping.” Corporate inversions are often followed by earnings-stripping, which makes U.S. profits appear, on paper, to be earned offshore. Corporations load the American part of the company with debt owed to the foreign part of the company. The interest payments on the debt are tax deductible, officially reducing American profits, which are effectively shifted to the foreign part of the company. The president’s proposal would address earnings-stripping by barring American companies from taking deductions for interest payments that are disproportionate to their revenue compared to their affiliated companies in other countries. This proposal is projected to raise $40.9 billion over a decade.

Another proposal in the president’s budget would tax excess returns from intangible property (like patents or copyrights) transferred to very low-tax countries, in order to crack down on the type of tax avoidance pharmaceutical companies like Pfizer and tech companies engage in.[15] There is already a category of offshore income (including interest and other passive income) for which U.S. corporations are not allowed to defer U.S. taxes. This proposal would, reasonably, add to that category “excess foreign income” (with “excess” defined as a profit rate exceeding 50 percent) from intangible property like trademarks, patents, and copyrights when such profits are taxed at an effective rate of less than 10 percent by the foreign country.

Multinational corporations can often use intangible assets to make their U.S. income appear to be “foreign” income. For example, a U.S. corporation might transfer a patent for some product it produces to its subsidiary in another country, say the Cayman Islands, that does not tax the income generated from this sort of asset. The U.S. parent corporation will then “pay” large fees to its subsidiary in the Cayman Islands for the use of this patent.

When it comes time to pay U.S. taxes, the U.S. parent company will claim that its subsidiary made huge profits by charging for the use of the patent it ostensibly holds, and that because those profits were allegedly earned in the Cayman Islands, U.S. taxes on those profits are deferrable (not due). Meanwhile, the parent company says that it made little or no profit because of the huge fees it had to pay to the subsidiary in the Cayman Islands (i.e., to itself). The arrangements used might be much more complex and involve multiple offshore subsidiaries, but the basic idea is the same. The president’s proposal would significantly restrict the use of these schemes and is projected to raise $21.3 billion over a decade.

Examples of Amendments that Would Improve the Effectiveness, or Reduce the Harm, of Provisions Included in the Tax Extenders

Some of the provisions among the tax extenders need to be reformed if they are to do any good for the American economy. For example, there are three types of reforms that Congress can make to the research credit to ensure that it actually accomplishes its goal of increasing research conducted by private firms.[16]

First, the definition of the type of research activity eligible for the credit could be clarified. One step in the right direction would be to enact the standards embodied in regulations proposed by the Clinton administration, which were later scuttled by the Bush administration. As it stands now, accounting firms are helping companies obtain the credit to subsidize redesigning food packaging and other activities that most Americans would see no reason to subsidize. The uncertainty about what qualifies as eligible research also results in substantial litigation and seems to encourage companies to push the boundaries of the law and often cross it.

Second, Congress could improve the rules determining which part of a company’s research activities should be subsidized. In theory, the goal is to subsidize only research activities that a company would otherwise not pursue, which is a difficult goal to achieve. But Congress can at least take the steps proposed by the Government Accountability Office to reduce the amount of tax credits that are simply a “windfall,” meaning money given to companies for doing things that they would have done anyway.

Third, Congress can address how and when firms obtain the credit. For example, Congress should bar taxpayers from claiming the credit on amended returns, because the credit cannot possibly be said to encourage research if the claimant did not even know about the credit until after the research was conducted.

There are other reforms that Congress could attach to a tax extenders bill that would address general problems with our tax system while also mitigating some of the worst features of the tax extenders. For example, the worst thing about the so-called “active financing exception” (aka GE Loophole) that was described earlier in this report is that it allows American corporations to defer paying U.S. taxes on their offshore financial income even while they immediately take deductions against their U.S. taxes for interest payments on debt used to finance the offshore operations. This problem would be addressed if Congress enacted the president’s proposal to bar interest deductions for offshore business until the profits from that offshore business are subject to U.S. taxes.

Under current law, American corporations essentially can borrow money to invest in foreign operations and immediately deduct the cost of that borrowing even though they can put off — forever if they choose — paying any U.S. taxes on the profits from those offshore operations. This is true for most types of multinational business. But it is even more alarming that this opportunity for tax avoidance is extended to financial firms with the active financing exception, given that financial firms would seem to have the most ability to exploit this weakness in the tax laws.

The president’s proposal would remove this opportunity for tax avoidance for all types of firms and remove the most worrying aspect of the active financing exception. The proposal is projected to raise $51.4 billion over a decade.

[1] Jeremy W. Peters, Senate Deal Is Reached on Restoring Jobless Aid, New York Times, March 13, 2014. http://www.nytimes.com/2014/03/14/us/senate-reaches-deal-to-pay-for-jobless-aid.html?hpw&rref=us&_r=0

[2] Citizens for Tax Justice, “Murray-Ryan Budget Deal Avoids Government Shutdown but Does Not Close a Single Tax Loophole, Leaves Many Problems in Place,” December 18, 2013. http://www.ctj.org/taxjusticedigest/archive/2013/12/murray-ryan_budget_deal_avoids.php

[3] Congressional Budget Office, “The Budget and Economic Outlook: 2014 to 2024,” February 4, 2014. http://www.cbo.gov/publication/45010

[4] Gary Guenther, Section 179 and Bonus Depreciation Expensing Allowances: Current Law, Legislative Proposals in the 112th Congress, and Economic Effects, September 10, 2012. http://www.fas.org/sgp/crs/misc/RL31852.pdf

[5] Citizens for Tax Justice, “Reform the Research Credit — Or Let It Die,” December 4, 2013. http://ctj.org/ctjreports/2013/12/reform_the_research_tax_credit_–_or_let_it_die.php

[6] Citizens for Tax Justice, “Don’t Renew the Offshore Tax Loopholes,” August 2, 2012. www.ctj.org/ctjreports/2012/08/dont_renew_the_offshore_tax_loopholes.php

[7] Christopher Helman, “What the Top U.S. Companies Pay in Taxes,” Forbes, April 1, 2010, http://www.forbes.com/2010/04/01/ge-exxon-walmart-business-washington-corporate-taxes.html.

[8] Gary Guenther, “Section 179 and Bonus Depreciation Expensing Allowances: Current Law, Legislative Proposals in the 112th Congress, and Economic Effects,” Congressional Research Service, September 10, 2012. http://www.fas.org/sgp/crs/misc/RL31852.pdf

[9] “Coalition to Congress: End the Wind Production Tax Credit,” September 24, 2013,

http://www.eenews.net/assets/2013/09/24/document_pm_02.pdf; Nicolas Loris, “Let the Wind PTC Die Down Immediately,” October 8, 2013. http://www.heritage.org/research/reports/2013/10/wind-production-tax-credit-ptc-extension

[10] Citizens for Tax Justice, “Don’t Renew the Offshore Tax Loopholes,” August 2, 2012. www.ctj.org/ctjreports/2012/08/dont_renew_the_offshore_tax_loopholes.php

[11] Senators Carl Levin and John McCain, Memorandum to Members of the Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations, May 21, 2013. http://www.hsgac.senate.gov/download/?id=CDE3652B-DA4E-4EE1-B841-AEAD48177DC4

[12] Elizabeth Lower-Basch, “Rethinking Work Opportunity: From Tax Credits to Subsidized Job Placements,” Center for Law and Social Policy, November 2011. http://www.clasp.org/resources-and-publications/files/Big-Ideas-for-Job-Creation-Rethinking-Work-Opportunity.pdf

[13] All of the revenue projections in this section are from Joint Committee on Taxation, “Estimated Budget Effects Of The Revenue Provisions Contained In The President’s Fiscal Year 2015 Budget Proposal,” JCX-36-14, April 15, 2014. https://www.jct.gov/publications.html?func=startdown&id=4586

[14] Citizens for Tax Justice, “The Problem of Corporate Inversions: The Right and Wrong Approaches for Congress,” May 14, 2014. http://ctj.org/ctjreports/2014/05/the_problem_of_corporate_inversions_the_right_and_wrong_approaches_for_congress.php

[15] Citizens for Tax Justice, “The President’s Fiscal Year 2015 Budget: Business Tax Reform Provisions,” March 12, 2014. http://www.ctj.org/ctjreports/2014/03/the_presidents_fiscal_year_2015_budget_business_tax_reform_provisions.php

[16] Each of these three types of reforms is explained in detail in Citizens for Tax Justice, “Reform the Research Credit — Or Let It Die,” December 4, 2013. http://ctj.org/ctjreports/2013/12/reform_the_research_tax_credit_–_or_let_it_die.php