March 12, 2014 12:00 AM | Permalink | ![]()

President Barack Obama’s proposed budget for the next fiscal year includes two broad categories of tax provisions. This report describes the provisions proposed by the President as a package of a business tax reforms. Provisions in the budget that mostly benefit individuals and families and raise revenue are described in another report from Citizens for Tax Justice.[1]

The provisions described in this report are proposed by the President as a part of a plan to overhaul, in a “revenue-neutral” way, how the tax code treats businesses. The President proposes to eliminate or limit several special breaks and loopholes enjoyed by businesses, but put all of the resulting revenue savings towards lowering the corporate tax rate from 35 percent to 28 percent and providing other breaks to businesses (like making permanent the tax credit for research).

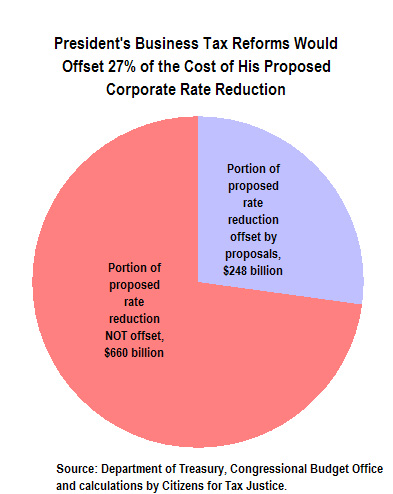

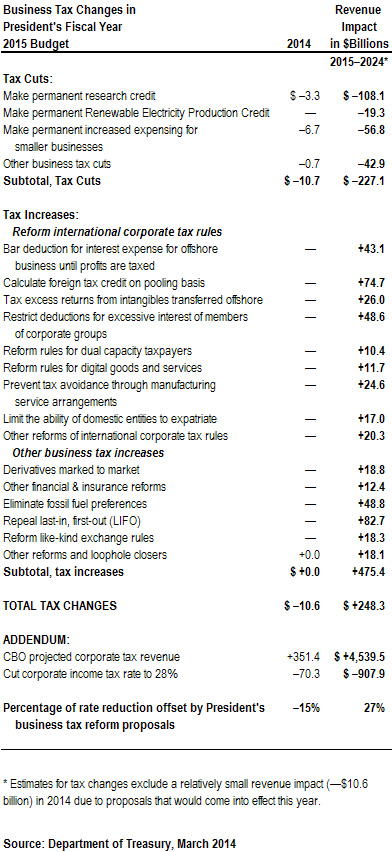

The net revenue increase projected to result from the business tax proposals the President lays out would offset just over a quarter of the total cost of lowering the statutory corporate income tax rate to 28 percent. Congress would be left to come up with additional ways to limit special breaks and loopholes to offset the rest of the cost. A reasonable and responsible way to move forward would be to first determine how much revenue the corporate income tax should collect and then determine how to meet that target with a reformed tax code. Attempting to achieve consensus on a massive rate reduction before figuring out how Congress would offset the costs sets the stage for a process that could simply become another round of unaffordable corporate tax breaks that reduce needed revenue.

Moreover, revenue neutrality is not an acceptable goal. It is simply unfair to not ask large, profitable corporations as a whole to contribute more to fund public investments like education, infrastructure and research that make their profits possible, and which are underfunded today. At a time when cuts have been made to investments like Head Start and medical research because of an alleged fiscal crisis, it is unfair for our leaders to refuse  to raise revenue from corporations and other businesses.

to raise revenue from corporations and other businesses.

The proposed dramatic reduction in the corporate income tax rate seems to be motivated by the common argument that the rate is relatively high and should be lowered to make the U.S. “competitive.” But, as explained below, most American corporations are already paying lower taxes in the U.S. than they pay in other countries where they do business.

The business tax provisions do include some proposals that could be enormously helpful if the resulting revenue savings were not used to provide new tax breaks to businesses. Some of the new proposals included this year are great improvements over previous versions.

For example, the provisions this year include a much stronger proposal to prevent “earnings stripping,” which occurs when corporations (both American and foreign) earn profits in the United States, but borrow large amounts from a foreign affiliate, often in a tax haven, generating large interest deductions for money essentially paid to themselves. The result is to sharply reduce their U.S. tax bills, sometimes to little or nothing. Citizens for Tax Justice criticized the “earnings stripping” reform proposal in a previous Obama budget as too weak.[2] The new proposal is a great improvement and is projected to increase revenue by ten times as much as the previous proposal.

Other new proposals designed to address international tax avoidance by multinational corporations include changing the outdated tax rules that apply to digital goods and services and tightening the rules to prevent American corporations from “expatriating” by arranging to be acquired by an offshore shell company. There are also other helpful reforms of our international tax rules.

In addition, there are new proposals to close domestic tax loopholes, including a proposal to reform the rules governing “like-kind exchanges,” which started out as a break for farmers exchanging land and has grown into a maneuver used by the real estate industry and huge corporations to save billions in taxes.

Tax Cut Proposals

Lower Corporate Tax Rate to 28 Percent

Ten-Year Revenue Impact: —$900 billion

The President proposes to limit and repeal corporate tax breaks and loopholes and use all of the revenue savings to “cut the corporate tax rate to 28 percent” from its current level of 35 percent.[3] This refers to the statutory corporate income tax rate, whereas the effective corporate income tax rate (the percentage of profits that corporations actually pay in corporate income taxes) is already much lower. Citizens for Tax Justice recently studied the Fortune 500 corporations that had been profitable in each of the previous five years and found that their effective rate over that period was just 19.4 percent.[4]

The President’s proposal to spend every dime of the revenue saved from ending corporate tax breaks and loopholes on reducing the corporate tax rate seems to be motivated by the argument that the U.S. corporate tax rate is relatively high and therefore should be lowered to make America “competitive.”

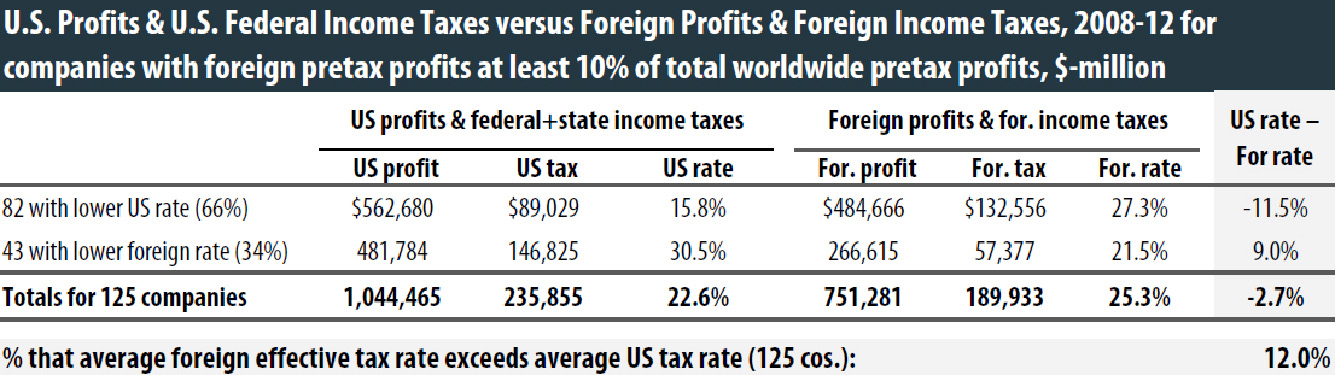

But the effective corporate income tax rate paid in the U.S. is often actually lower than the effective rates paid in other countries. The Citizens for Tax Justice study found that two-thirds of the profitable Fortune 500 corporations with significant offshore profits actually paid lower corporate taxes in the U.S. than they paid in the other countries where they did business over that five-year period examined.

While the Treasury Department and the Office of Management and Budget provide estimates of the revenue impacts of most of the President’s budget proposals, no estimate is provided for the cost of lowering the statutory rate from 35 percent to 28 percent. However, based on estimates of future corporate income tax receipts from the Congressional Budget Office, it appears that the cost over the next decade would be approximately $900 billion.[5]

Given the many funding cuts made in recent years to public investments that the American economy and American families depend on, the President should change his approach and propose a business tax reform that is revenue-positive rather than revenue-neutral. That would require amending his plan to include a much less dramatic reduction in the statutory rate — if any.

Expand and Make Permanent the Research Credit

Ten-Year Revenue Impact: —$108.1 billion

The President proposes to expand and make permanent the research and experimentation tax credit, a tax subsidy that is supposed to encourage businesses to perform research that benefits society. First enacted in 1981, the credit has been extended many times (often retroactively) but never made permanent. A recent report from Citizens for Tax Justice explains that the research credit is riddled with problems and should be either reformed dramatically or allowed to expire.[6]

As the report explains, the research credit subsidizes activities that do not benefit society in any clear way and/or subsidizes research that would have taken place even in the absence of the credit. Congress should enact no legislation to make permanent or extend the research credit unless the legislation includes three types of reforms.

First, the definition of the type of research activity eligible for the credit must be clarified. One step in the right direction would be to enact the standards embodied in regulations proposed by the Clinton administration, which were later scuttled by the Bush administration. As it stands now, accounting firms are helping companies obtain the credit to subsidize redesigning food packaging and other activities that most Americans would see no reason to subsidize. The uncertainty about what qualifies as eligible research also results in substantial litigation and seems to encourage companies to push the boundaries of the law and often cross it.

Second, Congress must improve the rules determining which part of a company’s research activities should be subsidized. In theory, the goal is to subsidize only research activities that a company would otherwise not pursue, which is a difficult goal to achieve. But Congress can at least take the steps proposed by the Government Accountability Office to reduce the amount of tax credits that are simply a “windfall,” meaning money given to companies for doing things that they would have done anyway.

Third, Congress must address how and when firms obtain the credit. For example, Congress should bar taxpayers from claiming the credit on amended returns, because the credit cannot possibly be said to encourage research if the claimant did not even know about the credit until after the research was conducted.

The report from Citizens for Tax Justice on the research credit explains each of these areas of potential reform in detail.

Make Permanent Increased Expensing for Small Businesses (Section 179 Expensing)

Ten-Year Revenue Impact: —$56.8 billion

Firms are allowed to deduct their business expenses each year. Capital expenses (expenditures to acquire assets that generate income over a long period of time) usually must be deducted over a number of years to reflect their ongoing usefulness. So the expenses that go towards developing a capital asset, like improvements in a building used for the business, will be deducted over several years. In most cases firms would rather deduct capital expenses right away rather than delaying those deductions, because of the time value of money, i.e., the fact that a given amount of money is worth more today than the same amount of money will be worth if it is received later. For example, $100 invested now at a 7 percent return will grow to $200 in ten years.

Congress has showered businesses with several types of depreciation breaks, that is, breaks allowing firms to deduct the cost of acquiring or developing a capital asset more quickly than that asset actually wears out. There are massive accelerated depreciation breaks that are a permanent part of the tax code as well as some smaller breaks, like section 179, which allows smaller businesses to write off most of their capital investments immediately (up to certain limits).

A report from the Congressional Research Service reviews efforts to quantify the impact of depreciation breaks and explains that “the studies concluded that accelerated depreciation in general is a relatively ineffective tool for stimulating the economy.”[7]

One positive thing that can be said about section 179 is that it is more targeted towards small business investment than any of the other tax breaks that are alleged to help small businesses.

Section 179 allows firms to deduct the entire cost of a capital purchase (to “expense” the cost of a capital purchase) up to certain limits that have been increased by legislation that has recently expired. The President proposes to extend and make permanent these increases. The President’s proposal would allow expensing of up to $500,000 of purchases of certain capital investments (generally, equipment but not land or buildings). The deduction is reduced a dollar for each dollar of capital purchases exceeding $2 million, and the total amount expensed cannot exceed the business income of the taxpayer. These limits would be indexed for inflation.

These limits mean that section 179 generally does not benefit large corporations like General Electric or Boeing, even if the actual beneficiaries are not necessarily what ordinary people think of as “small businesses.”

There is little reason to believe that business owners big or small respond to anything other than demand for their products and services. But to the extent that a tax break could possibly prod small businesses to invest, section 179 is somewhat targeted to accomplish that goal.

Revenue-Raising Proposals

Bar Deduction for Interest Expense for Offshore Business until Profits are Taxed

Ten-Year Revenue Impact: +$43.1 billion

The President proposes to require that U.S. companies defer deductions for interest expenses related to earning income abroad until that income is subject to U.S. taxation (if ever).

U.S. multinational companies are allowed to “defer” U.S. taxes on income generated by their foreign subsidiaries until that income is officially brought to the U.S. (“repatriated”). There are numerous problems with deferral, but it’s particularly problematic when a U.S. company defers U.S. taxes on foreign income for years even while it deducts the expenses of earning that foreign income immediately to reduce its U.S. taxable profits. For example, an American corporation could borrow to buy stock in a foreign corporation and deduct the interest payments on that debt immediately even if it defers for years paying U.S. taxes on the profits from the investment in the foreign company. In this situation, the tax code effectively subsidizes American corporations for investing offshore rather than in the U.S.

Under the President’s proposal, the share of interest payments on debt used to invest abroad that could be deducted would be limited to the share of income from those offshore investments that is subject to U.S. taxes in a given year. The rest of the deductions for interest payments would be deferred, just as U.S. taxes on the rest of the offshore profits are deferred.

The version of this proposal included in the President’s first budget was stronger because it would have required that U.S. companies defer deductions for all expenses (other than research and experimentation expenses) relating to earning income abroad until that income is subject to U.S. taxation. The current proposal only applies to interest expenses.

Calculate Foreign Tax Credits on a “Pooling” Basis

Ten-Year Revenue Impact: +$74.7 billion

The President’s proposal would require that the foreign tax credit be calculated on a consolidated basis, or “pooling basis,” in order to prevent corporations from taking the credit in excess of what is necessary to avoid double-taxation on their foreign profits.

The foreign tax credit allows American corporations to subtract whatever corporate income taxes they have paid to foreign governments from their U.S. tax bill. This makes sense in theory, because it prevents the offshore profits of American corporations from being double-taxed.

But, unfortunately, corporations sometimes get foreign tax credits that exceed the U.S. taxes that apply to such income, meaning that the U.S. corporations are using foreign tax credits to reduce their U.S. taxes on their U.S. profits, not just avoiding double taxation on their foreign income.

For example, say a U.S. corporation owns two foreign subsidiaries, one in a country where it actually does business and pays taxes, the other in a tax haven where it does no real business and pays no taxes. The U.S. corporation has accumulated profits in both foreign subsidiaries. If the U.S. company decides to officially bring some of its foreign profits back to the U.S., it can say that the profits it has “repatriated” all came from the taxable foreign corporation, thereby maximizing its foreign tax credit that it can use to reduce its U.S. tax on the repatriation.

Under the President’s proposal, the U.S. corporation would be required to compute the foreign tax credit as if the dividend was paid proportionately from each of its foreign subsidiaries. Since no foreign tax was paid on the profits in the tax haven, this approach will reduce the U.S. company’s foreign tax credit to the correct amount.

Tax Excess Returns from Intangibles Transferred Offshore

Ten-Year Revenue Impact: +$26.0 billion

The President proposes to bar American corporations from deferring their U.S. taxes on “excess income” from intangible property that is technically held offshore in extremely low-tax countries. There is already a category of offshore income (including interest and other passive income) for which U.S. corporations are not allowed to defer U.S. taxes. This proposal would, reasonably, add to that category “excess foreign income” (with “excess” defined as a profit rate exceeding 50 percent) from intangible property like trademarks, patents, and copyrights when such profits are taxed at an effective rate of less than 10 percent by the foreign country.

As already explained, a U.S. multinational corporation that has offshore subsidiaries does not have to pay U.S. taxes on the income generated abroad until that income is officially brought to the U.S. (until that income is “repatriated”). Figuring out how much of the income is generated in the U.S. and how much is generated abroad is therefore critical. If a multinational company can characterize most of its income as “foreign” it can reduce or even eliminate the U.S. taxes on that income.

Multinational corporations can often use intangible assets to make their U.S. income appear to be “foreign” income. For example, a U.S. corporation might transfer a patent for some product it produces to its subsidiary in another country, say the Cayman Islands, that does not tax the income generated from this sort of asset. The U.S. parent corporation will then “pay” large fees to its subsidiary in the Cayman Islands for the use of this patent.

When it comes time to pay U.S. taxes, the U.S. parent company will claim that its subsidiary made huge profits by charging for the use of the patent it ostensibly holds, and that because those profits were allegedly earned in the Cayman Islands, U.S. taxes on those profits are deferrable (not due). Meanwhile, the parent company says that it made little or no profit because of the huge fees it had to pay to the subsidiary in the Cayman Islands (i.e., to itself).

The arrangements used might be much more complex and involve multiple offshore subsidiaries, but the basic idea is the same.

There is a section of the tax code (commonly known as subpart F) that bars deferral for certain types of income like dividends, interest and royalties that are very easy to shift around from one country to another in order to avoid taxes. But subpart F is currently riddled with exceptions and frequently avoided.

The President’s proposal would amend subpart F to include “excess” profits from the sale or transfer of intangible assets from an American corporation to an offshore subsidiary corporation, when the foreign country effectively taxes those profits at an effective rate of less than 10 percent. (The rule would partially apply when the profits are taxed by the foreign country at an effective rate between 10 and 15 percent.) “Excess” is not defined by the Treasury, but the Joint Committee on Taxation has explained that legislative language provided to it by the administration defined “excess” profits as profits exceeding 50 percent (meaning the return on the investment exceeds 150 percent of the cost).[8]

While this provision would effectively prevent certain types of tax avoidance by American corporations using offshore tax havens, its complexity underscores how much more straightforward it would be if Congress simply repealed deferral, so that there would be no tax advantage at all from making U.S. profits appear to be earned in a low-tax country.

Restrict Deductions for Excessive Interest of Members of Corporate Groups

Ten-Year Revenue Impact: +$48.6 billion

The President proposes to create new rules to restrict “earnings stripping,” the practice of multinational corporations earning profits in the United States reducing or eliminating their U.S. profits for tax purposes by making large interest payments to their foreign affiliates.

The President would allow a multinational corporation doing business in the U.S. to take deductions for interest payments to its foreign affiliates only to the extent that the U.S. entity’s share of the interest expenses of the entire corporate group (the entire group of corporations owned by the same parent corporation) is proportionate to its share of the corporate group’s earnings (calculated by adding back interest expenses and certain other deductible expenses). The corporation doing business in the U.S. could also choose instead to be subject to a different rule, limiting deductions for interest payment to ten percent of “adjusted taxable income” (which is taxable income plus several amounts that are usually deducted for tax purposes).

Most of the President’s international tax reform proposals address situations in which American corporations attempt to claim that their U.S. profits are actually earned by their affiliated corporations in other countries. This proposal is different in that it also addresses situations in which the American corporation is itself a subsidiary of a foreign corporation (at least on paper, since the foreign corporation can actually be a shell corporation in a tax haven).

In this situation, the American company is subject to U.S. corporate income taxes, but “earnings stripping” is used to make the American profits appear to be earned by the foreign corporation and thus not taxable in the U.S. To accomplish this, the U.S. company is loaded up with debt that is owed to the affiliated foreign company. The U.S. company then makes large interest payments (which reduce or wipe out its taxable income) to the foreign company.

Section 163(j) of the tax code was enacted in 1989 to prevent this practice, but it seems to be failing. It bars corporations from taking deductions for interest payments if their debt is more than one and a half times their equity (capital invested by stockholders) and the interest exceeds 50 percent of the company’s “adjusted taxable income” (taxable income plus several amounts that are usually deducted for tax purposes).

The problem is that an American corporation could have debt and interest payments that are below these thresholds but still high relative to the rest of the corporate group (the rest of the corporations all ultimately owned by the same parent corporation). For example, imagine a foreign corporation owns five subsidiary corporations, one in the U.S. and the other four in countries with much lower tax rates or no corporate income tax at all. If the American corporation tells the IRS that it generated a fifth of the revenue of the corporate group but also has half of the interest expense of the entire group, the IRS ought to be able to surmise that this has been arranged to artificially reduce U.S. profits to avoid U.S. taxes — even if the thresholds for the existing section 163(j) have not been breached. This is one of the problems that the President’s proposal would address.

This measure is much stronger than the one proposed to address earnings stripping in the President’s previous budget plan, which only targeted those corporations that could be identified as “inverted” corporations.[9] (The President also has a new proposal to prevent inversions generally, which is discussed later on.)

Reform Rules for “Dual Capacity” Taxpayers

Ten-Year Revenue Impact: +$10.4 billion

The President proposes to end the practice by some multinational corporations of taking foreign tax credits for payments made to foreign governments that are not really taxes.

Dual capacity taxpayers generally are corporations that make two types of payments to foreign governments. One type of payment is some form of corporate income tax, while another type is a royalty or fee or other type of payment made in return for a particular economic benefit. The U.S. tax code allows American corporations to take a credit for corporate income taxes they pay to foreign governments, to avoid double-taxation of foreign income. The problem is that the current rules sometimes allow these corporations to take foreign tax credits for non-tax payments they make to foreign governments. This of course has nothing to do with avoiding double-taxation, which is the sole purpose of the foreign tax credit.

The problem began in the 1950s, when the U.S. wanted to ensure that American oil companies expanded their activities in Middle East oil countries. So at the insistence of the State Department, the IRS was forced to allow oil companies to treat the royalties they paid to Saudi Arabia and other oil-rich countries for oil as corporate income taxes. This was great for the oil companies, because it meant that those royalties resulted in not just a tax deduction but a foreign tax credit, then worth twice as much as a deduction. (These days, a corporate tax credit is worth three times as much as a deduction.)

This loophole is supposed to be more limited now, but the limits are ineffective. The oil companies can arrange with a foreign government to impose a “tax” on an oil company — even though it doesn’t impose corporate income taxes on any other type of company — and the oil company is allowed to “prove” that this “tax” is not a royalty by showing it’s not a payment for a “specific economic benefit.” But this is not credible on its face, because the economic benefit is obviously the right to extract the oil. Companies operating in a country without a tax on business income can use a safe harbor in the U.S. tax rules allowing them to treat a portion of their royalties as taxes without proving anything at all.

The President’s proposal would change the rules so that only foreign corporate income taxes that are applied generally to all types of companies will be creditable.

Reform Rules for Digital Goods and Services

Ten-Year Revenue Impact: +$11.7 billion

The President proposes to bar American corporations from deferring U.S. taxes on income that is officially earned offshore if it comes from digital goods or services, which have no obvious “location” in any meaningful sense.

As already explained, there is a section of the tax code (commonly known as subpart F) that bars deferral for certain types of offshore income like dividends, interest and royalties that are very easy to shift around from one country to another in order to avoid taxes.

The President’s proposal would amend subpart F to apply to offshore income “from the lease or sale of a digital copyright article or from the provision of a digital service” when the subsidiary does not actually develop the intangible asset generating the income.

The administration explains that under the existing rules, whether or not subpart F applies (whether or not deferral is disallowed) depends on whether the transaction takes the form of a lease, sale, or provision of a service. This distinction makes little sense today, because a company that wants to transfer a copyrighted article (for example) to another party for a price can achieve the same result whether the arrangement is set up as a sale, lease or a provision of a service.

Prevent Tax Avoidance through Manufacturing Service Arrangements

Ten-Year Revenue Impact: +$24.6 billion

The President proposes to tighten rules meant to prevent tax avoidance by American corporations using offshore subsidiaries to buy and sell property manufactured in the U.S. (or other countries other than where the subsidiaries are located).

The category of offshore income for which American corporations are not allowed to defer U.S. taxes (“subpart F income”) already includes income that their offshore subsidiaries earn from buying property manufactured in a country other than where they are located and then selling it to another party, when either the seller or buyer is the American parent corporation (or some other related corporation).

Some companies have apparently found a loophole in this rule by arguing their arrangements involve the offshore subsidiary paying for the service of manufacturing the property rather than the property itself, before they go on to sell the property at a profit.

Under the President’s proposal, U.S. taxes could not be deferred for the profits earned by the offshore subsidiaries from selling the property, regardless of whether the subsidiaries obtained the property by buying it or paying for its manufacture.

Limit the Ability of Domestic Entities to Expatriate

Ten-Year Revenue Impact: +$17.0 billion

The President proposes to strengthen the rules that are supposed to prevent U.S. corporations from claiming that they have become “foreign” corporations in order to avoid U.S. taxes.

It used to be that U.S. tax law was so weak in this area that an American corporation could reincorporate in a known tax haven like Bermuda and declare itself a non-U.S. corporation, a practice often called “inversion.” (Technically a new corporation would be formed in the tax haven country that would then acquire the U.S. corporation.) In theory, any profits it earned in the U.S. at that point should be subject to U.S. taxes, but profits earned by subsidiaries in other countries would then be out of reach of the U.S. corporate tax.

But the more significant impact was that these corporations could gain even greater tax savings by making profits really earned in the U.S. appear to be earned offshore. One maneuver used by inverted companies to make their U.S. profits appear to be offshore profits is “earnings stripping,” which has already been described. A 2007 Treasury study concluded that a section of the code enacted in 1989 to prevent earnings-stripping (section 163(j)) did not seem to prevent inverted companies from doing it.

Congress attempted to address this issue with the “anti-inversion” provisions of the American Jobs Creation Act (AJCA) of 2004, resulting in the current section 7874 of the tax code. This section treats an ostensibly foreign corporation as a U.S. corporation for tax purposes if (1) it resulted from an inversion that was accomplished (meaning the U.S. corporation became, at least on paper, obtained by a corporation incorporated abroad) after March 4, 2003, (2) the shareholders of the American corporation own 80 percent or more of the voting stock in the new corporation, and (3) the new corporation does not have substantial business activities in the country in which it is incorporated.

Section 7874 provides much less severe tax consequences for corporations that meet these criteria except that shareholders of the American company now own between 60 percent and 80 percent (rather than 80 percent or more) of the voting stock in the newly formed corporation.

A recent New York Times article highlights how corporations today can sometimes get around section 7874 by merging with an existing foreign corporation.[10] In some of these cases, it may be that the new corporations are not 80 percent owned by the shareholders of the American corporation. They may be 60 percent owned by the owners of the American corporation, but the less severe tax consequences that apply may fail to deter inversions.

The President’s proposal would make several changes to section 7874. It would change the 80 percent threshold to 50 percent (meaning the corporations could be taxed as an American corporation if the shareholders of the American corporation have 50 percent or more of the stock in the newly formed (ostensibly) foreign corporation) and eliminate the milder tax consequences for corporations that only meet the 60 percent threshold.

Perhaps more significantly, the new corporation could also be taxed as an American corporation (regardless of how much the ownership has changed or not changed) if it has substantial business in the U.S. and is managed and controlled in the U.S.[11] In other words, an American corporation will not be able to claim that it has become a foreign corporation when its headquarters is still clearly physically located in the U.S.

Derivatives Marked to Market

Ten-Year Revenue Impact: +$18.8 billion

The President proposes to subject most derivatives to what is called “mark-to-market” taxation. The same proposal has been included by Congressman Dave Camp in his tax reform proposal.

A derivative can be thought of as a contract between two parties to make some sort of transaction and that has a value derived from the underlying asset involved in that transaction. For example, two people can enter into a contract that gives party A the right to buy stock from party B at a certain price in the future. If the value of the stock rises above that price, party A wins (he gets to buy the stock at less than its value) and party B loses (he has to sell the stock at less than its value). Conversely, if the stock value turns out to be less than the contract price, party B wins (and party A loses).

Derivatives can be useful financial tools for businesses, particularly for hedging risks. For example, a farm business may want to reduce risk by setting a future price for its crops at a certain level. So the farm agrees to sell the crops at a future date at that certain price. The buying party is betting that the value of the crops will be higher in the future. This “hedging” may or may not turn out to maximize the farm’s profits, but the business can eliminate its downside risk.

In recent years, derivatives have become far more complex, particularly as they have become traded by individual and corporate investors who have no connection to or interest in the underlying assets. For example, imagine that neither party in the contract described above actually owns or plans to buy the crops that the contract refers to. The contract really is just a bet by the two parties on which way the crops’ value will move.

Derivatives can also create huge opportunities for tax avoidance. To take just one example, some high-profile people of enormous wealth have used derivatives to avoid capital gains taxes.[12] Such an arrangement can involve lending appreciated stock to an investment bank for several years with an agreement to sell the stock to the bank at a discounted price, while also hedging against the risk that the stock would lose value. Under this arrangement, the individual is economically in the same position as having sold the stock — he received cash for the stock and did not bear the risk of the stock losing value — and yet he does not have to pay tax on the capital gains until several years later, when the sale of the stock technically occurs under the contact.

Under the President’s proposal, at the end of each year, gains and losses from derivatives would be included in income, even if the derivatives were not sold. All profits (and losses) would be treated as “ordinary,” meaning that they would be treated as regular income and would be ineligible for the special low tax rates on capital gains. However, this would not be required for derivatives that really are used to hedge business risks.

The result would be that the types of tax dodges described above would no longer provide any benefit. The taxpayers would not bother to enter into those contracts because they would be taxed at the end of the year on the value of the contracts (meaning they are unable to defer taxes on capital gains) and the gains would be taxed at ordinary income tax rates.

Eliminate Fossil Fuel Tax Preferences

Ten-Year Revenue Impact: +$48.8 billion

The President proposes to end several tax breaks that subsidize the extraction and sale of oil, natural gas and coal. These reforms are justified as a way to help the environment by redirecting resources away from dirty fuels, and also simply because it does not make economic sense for the government to give tax subsidies to an industry that is already extremely profitable. Most of the revenue raised from ending tax breaks for fossil fuels would come from three proposals in this category.

One proposal in this category would repeal the deduction for “intangible” costs of exploring and developing oil and gas sources. The “intangible” costs of exploration and development generally include wages, costs of using machinery for drilling and the costs of materials that get used up during the process of building wells. Most businesses must write off such expenses over the useful life of the property, but oil companies, thanks to their lobbying clout, get to write these expenses off immediately.

Another proposal in this category would repeal “percentage depletion” for oil and gas properties. Most businesses must write off the actual costs of their property over its useful life (until it wears out). If oil companies had to do the same, they would write off the cost of oil fields until the oil was depleted. Instead, some oil companies get to simply deduct a flat percentage of gross revenues. The percentage depletion deductions can actually exceed costs and can zero out all federal taxes for oil and gas companies. The Energy Policy Act of 2005 actually expanded this provision to allow more companies to enjoy it.

The President also proposes to bar oil and gas companies from using the manufacturing tax deduction. The manufacturing tax deduction was added to the law in 2004 and allows companies to deduct 9 percent of their net income from domestic production. Some might wonder why oil and gas companies can use a deduction for “manufacturing” in the first place. But Congress specifically included “extraction” in the definition of manufacturing so that it included oil and gas production, obviously at the behest of the industry.

Repeal Last-In, First-Out (LIFO) Accounting

Ten-Year Revenue Impact: +$82.7 billion

The President proposes to repeal the “last-in, first-out” or LIFO, inventory rule allowing companies to manipulate their inventory accounting to make their profits appear smaller than they actually are. LIFO allows companies to deduct the (higher) cost of recently acquired or produced inventory, rather than the (lower) cost of older inventory.

For example, we normally think of profit this way: You buy something for $30 and sell it for $50 so your profit is $20 (ignoring any other expenses). But the LIFO method used by some businesses, notably oil companies, doesn’t fit this picture. They might buy oil for $30 a barrel, and when the price rises they might buy some more for $45 a barrel. But when they sell a barrel of oil for $50, they get to assume that they sold the very last barrel they bought, the one that cost $45. That means the profit they report to the IRS is $5 instead of $20.

This “last-in, first-out” rule (LIFO) has been in place for decades, and critics have long called for its repeal. In 2005, the then-Republican-led Senate tried to repeal it for oil and gas companies. (The provision was dropped from legislation in conference, so oil companies still get to use LIFO.) The Obama administration has, reasonably, proposed repeal of LIFO.

Reform Like-Kind Exchange Rules

Ten-Year Revenue Impact: +$18.3

The President proposes to limit the taxes that can be deferred under existing rules for profits from “like-kind exchanges” to $1 million. This limit would be indexed to inflation.

Businesses can take tax deductions for depreciation on their properties, and then sell these properties at an appreciated price while avoiding capital gains tax, through what is known as a “like-kind exchange.” The break was originally intended for situations in which two ranchers or two farmers decided to trade some land. Since neither had sold their land for cash and they were still using the land to make a living, it seemed reasonable at the time to waive the rules that would normally define this as a sale and tax any gains from it.

But the break has turned into a multi-billion-loophole that has been widely exploited by many giant companies, including General Electric, Cendant and Wells Fargo.[13] In fact, the “tax expenditure report” of the Joint Committee on Taxation (JCT) shows that most of the revenue lost as a result of this tax expenditure actually goes to corporations, not individuals.[14]

By limiting the tax deferral for like-kind exchanges to $1 million, the President’s proposal ensures that the break is less abused than it is today.

[1] Citizens for Tax Justice, “The President’s Fiscal Year 2015 Budget: Provisions to Benefit Individuals and Raise Revenue,” March 12, 2014. https://ctj.sfo2.digitaloceanspaces.com/pdf/obamabudgetfy2015.pdf

[2] Citizens for Tax Justice, “How Congress Can Fix the Problem of Tax-Dodging Corporate Mergers,” October 10, 2013. http://www.ctj.org/taxjusticedigest/archive/2013/10/how_congress_can_fix_the_probl.php

[3] Office of Management and Budget, “The President’s Budget Fiscal Year 2015: Opportunity for All: Building a 21st Century Infrastructure,” March, 2014. http://www.whitehouse.gov/sites/default/files/omb/budget/fy2015/assets/fact_sheets/building-a-21st-century-infrastructure.pdf

[4] Citizens for Tax Justice and the Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, “The Sorry State of Corporate Taxes,” February 26, 2014. http://www.ctj.org/corporatetaxdodgers/

[5] Congressional Budget Office, “The Budget and Economic Outlook: 2014 to 2024,” February 2014. www.cbo.gov/publication/45010

[6]Citizens for Tax Justice, “Reform the Research Credit – Or Let It Die,” December 4, 2013. www.ctj.org/ctjreports/2013/12/reform_the_research_tax_credit_–_or_let_it_die.php

[7] Gary Guenther, “Section 179 and Bonus Depreciation Expensing Allowances: Current Law, Legislative Proposals in the 112th Congress, and Economic Effects,” Congressional Research Service, September 10, 2012. http://www.fas.org/sgp/crs/misc/RL31852.pdf

[8] Joint Committee on Taxation, “Description Of Revenue Provisions Contained In The President’s Fiscal Year 2013 Budget Proposal,” JCS-2-12, June 18, 2012, page 342. https://www.jct.gov/publications.html?func=startdown&id=4465

[9] Citizens for Tax Justice, “How Congress Can Fix the Problem of Tax-Dodging Corporate Mergers,” October 10, 2013. http://www.ctj.org/taxjusticedigest/archive/2013/10/how_congress_can_fix_the_probl.php

[10] David, Gelles, “New Corporate Tax Shelter: A Merger Abroad,” New York Times, October 8, 2013. http://dealbook.nytimes.com/2013/10/08/to-cut-corporate-taxes-a-merger-abroad-and-a-new-home/?_php=true&_type=blogs&hp&_r=1

[11] This “management and control” standard arguably should apply to any corporations, even if they do not involve officially acquiring a corporation that was officially an American corporation. The Stop Tax Haven Abuse Act, introduced by Senator Carl Levin, would do this.

[12] Citizens for Tax Justice, “Derivatives Proposal from Top House Tax-Writer Could Improve Tax Code — if the Revenue Is Not Used for Rate Cuts,” February 4, 2013. http://ctj.org/ctjreports/2013/02/derivatives_proposal_from_top_house_tax-writer_could_improve_tax_code_–_if_the_revenue_is_not_used.php

[13] David Kocieniewski, “Major Companies Push the Limits of a Tax Break,” The New York Times, January 6, 2013. http://www.nytimes.com/2013/01/07/business/economy/companies-exploit-tax-break-for-asset-exchanges-trial-evidence-shows.html?pagewanted=all&_r=0

[14] Joint Committee on Taxation, “Estimates Of Federal Tax Expenditures For Fiscal Years 2012-2017,” JCS-1-13, February 01, 2013. https://www.jct.gov/publications.html?func=startdown&id=4503