June 29, 2016 09:00 AM | Permalink | ![]()

A new distributional analysis of Republican Speaker of the House Paul Ryan’s “A Better Way” policies finds that the plan would:

• Add $4 trillion to the national debt over a decade.

• Overwhelmingly benefit the top 1 percent of tax payers while resulting in a net loss for the bottom 95 percent of taxpayers.

• Slash corporate tax collections by at least half.

Top 1 Percent Would Enjoy Largest Tax Cuts Under the House Plan

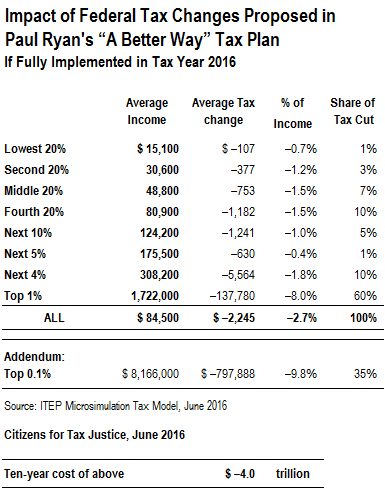

The so-called “A Better Way” plan would reduce taxes for the top 1 percent of Americans (a group with average annual household income of $1.7 million) by an average of $137,780 per year. This massive tax reduction for the rich equals a 60 percent share of all the individual tax cuts. The top 0.1 percent of Americans would receive $798,000 a year in tax cuts or a 35 percent share of the total tax reductions.

The plan includes across-the-board tax cuts for all taxpayers, but these cuts are much smaller for middle- and low-income families, both as a share of their annual incomes and as a share of the entire value of the tax plan. For example, the middle 20 percent of Americans would receive tax cuts averaging $753 a year under the proposal (equal to 1.5 percent of income) and the poorest 20 percent would see average tax cuts of $107 a year (0.7 percent of income) compared to the top 1 percent whose average tax cut would be 8 percent of income under Ryan’s proposal.

The individual tax cuts are extremely regressive because Ryan’s plan would repeal or sharply reduce two taxes that fall exclusively or mostly on the best-off Americans — the federal estate tax and the corporate income tax — while also slashing personal income taxes on investment income such as capital gains and dividends, which mostly go to the highest earners.

Altogether, CTJ’s analysis finds that the personal income tax changes would lose $1.2 trillion, the corporate tax changes $2.5 trillion and the estate tax changes $0.3 trillion over 10 years. In other words, the corporate tax cuts make up the bulk of the plan’s tax breaks.

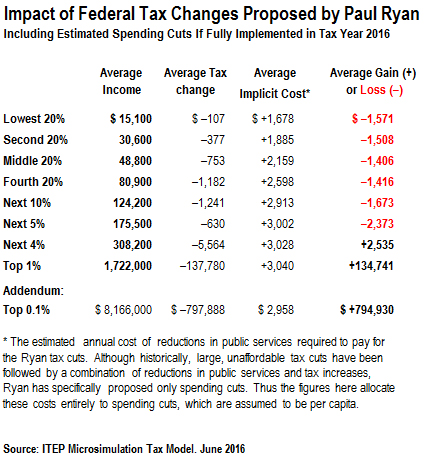

By themselves, the tax cut figures do not show the full regressive effects of the proposed tax changes. Ryan has proposed large reductions in federal programs to offset the cost of the tax reductions. When the impact of these program cuts is considered, only the richest 5 percent of Americans would end up better off. All other income groups would be net losers under the plan.

Modeling Issues

While much of the Ryan tax program is straightforward to analyze, two parts are problematic or unclear.

International taxation issue

The Ryan plan appears to propose a 20 percent tariff on goods and services imported into the United States and a tax exemption (or 20 percent tax credit) for goods and services exported to foreign countries. Although Ryan briefly argues that this scheme would not violate U.S. treaties with other countries, we do not agree.

In making the case for his tariff and rebate proposal, Ryan suggests that his business tax is similar to a value-added tax (a.k.a. a national sales tax). But while there are some similarities, it is decidedly not a VAT. It might better be characterized as a value-added tax with a deduction for value added. That’s because, unlike typical VATs, Ryan’s plan would allow a tax deduction for wages (the source of most value added).

In 2005, a tax panel set up by then-President George W. Bush made a similar proposal but concluded that it was unlikely to pass muster and excluded it from its analysis of its own plan. The panel’s report states: “given the uncertainty over whether border adjustments would be allowable under current trade rules, and the possibility of challenge from our trading partners, the Panel chose not to include any revenue that would be raised through border adjustments.” Most tax experts would agree that the plan would not pass muster.

Thus, we have not scored the effects of Ryan’s tariff and rebate proposal for either revenue or distributional purposes. Had we done so, the revenue loss from the plan would be greater, and the distributional effects of the plan would be even more regressive.

Business taxes on pass-through entities

It’s unclear whether Ryan intends to apply his 20 percent corporate tax to pass-through entities such as sole proprietorships, partnerships and Subchapter S corporations. He never explicitly says he would do so, but he does say that such entities would be required to pay their owner-operators an estimated “reasonable” salary, which would be deductible at the entity level. (This would be somewhat like the current treatment of Subchapter S corporations for payroll tax purposes.) If Ryan’s 20 percent corporate tax rate would apply to the remainder of pass-through income, then the cost of the plan would probably be higher, and the distributional effects would be even more regressive.

Appendix: Proposed Policy Changes in the House GOP Plan

- Consolidate the current seven personal income tax brackets into three brackets with a top rate of 33 percent.

- Lower the current preferential tax rates on capital gains and dividends by providing a 50 percent exclusion for capital gains, dividends and interest income.

- Eliminate itemized deductions, with the exception of charitable deductions and the mortgage interest deduction, while increasing standard deduction to $24,000 for married couples.

- Cap personal income tax rates on the “active income” of pass-through businesses at 25 percent.

- Repeal personal and dependent exemptions, while increasing the current $1,000 per child tax credit from $1,000 to $1,500 and allowing a new nonrefundable $500 tax credit for dependents not eligible for the current child tax credit.

- Eliminate the estate tax, the 3.8 percent Medicare tax on very high earners’ investment income and earned income.

- Eliminate the alternative minimum tax.

- Sharply reduce the corporate tax rate from 35 to 20 percent.

- Introduce a “territorial” corporate tax system which would exempt corporate income reported in other countries.

- Allow immediate tax write-offs for all business investments (except land).

- Eliminate the deductibility of net business interest payments (except for financial companies).