October 5, 2015 03:12 PM | Permalink | ![]()

The Use of Offshore Tax Havens by Fortune 500 Companies

Download Dataset/Appendix (XLS)

Most of America’s Largest Corporations Maintain Subsidiaries in Offshore Tax Havens

Cash Booked Offshore for Tax Purposes by U.S. Multinationals Doubled between 2008 and 2013

Evidence Indicates Much of Offshore Profits are Booked to Tax Havens

Firms Reporting Fewer Tax Haven Subsidiaries Do Not Necessarily Dodge Fewer Taxes Offshore

Measures to Stop Abuse of Offshore Tax Havens

Executive Summary:

U.S.-based multinational corporations are allowed to play by a different set of rules than small and domestic businesses or individuals when it comes to the tax code. Rather than paying their fair share, many multinational corporations use accounting tricks to pretend for tax purposes that a substantial portion of their profits are generated in offshore tax havens, countries with minimal or no taxes where a company’s presence may be as little as a mailbox. Multinational corporations’ use of tax havens allows them to avoid an estimated $90 billion in federal income taxes each year.

Congress, by failing to take action to end to this tax avoidance, forces ordinary Americans to make up the difference. Every dollar in taxes that corporations avoid by using tax havens must be balanced by higher taxes on individuals, cuts to public investments and public services, or increased federal debt.

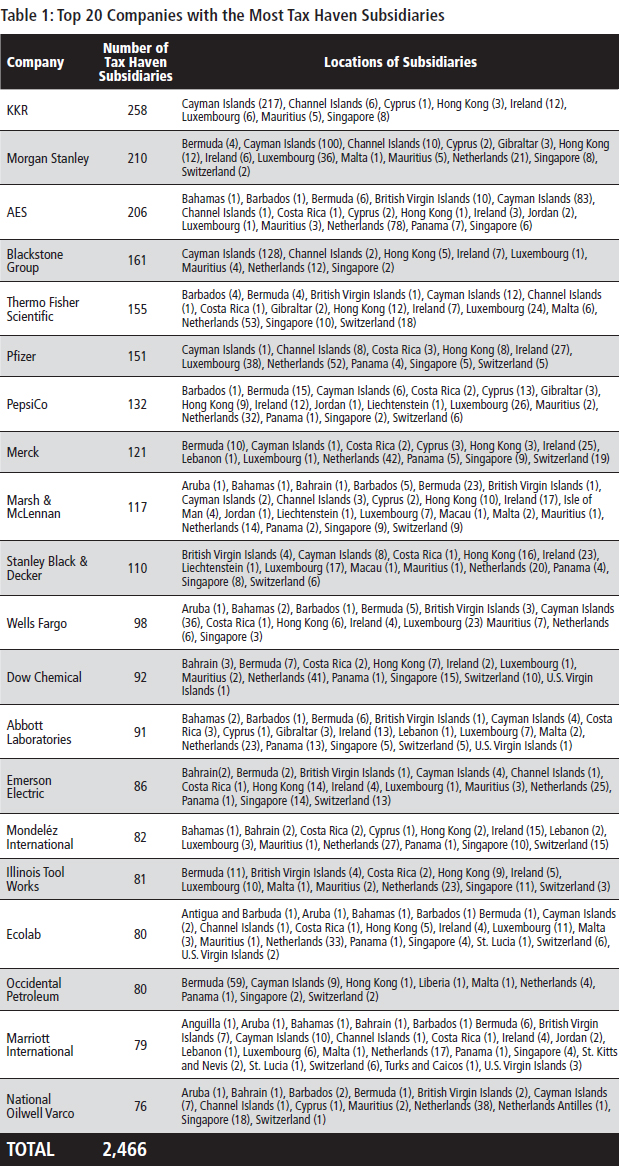

This study examines the use of tax havens by Fortune 500 companies in 2014. It reveals that tax haven use is ubiquitous among America’s largest companies and that a narrow set of companies benefits disproportionately.

Most of America’s largest corporations maintain subsidiaries in offshore tax havens. At least 358 companies, nearly 72 percent of the Fortune 500, operate subsidiaries in tax haven jurisdictions as of the end of 2014.

-All told, these 358 companies maintain at least 7,622 tax haven subsidiaries.

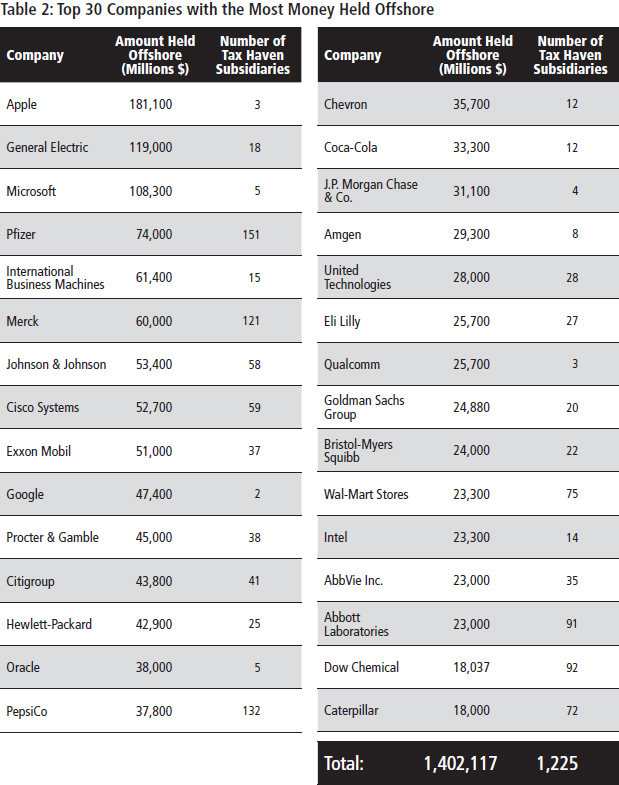

-The 30 companies with the most money officially booked offshore for tax purposes collectively operate 1,225 tax haven subsidiaries.

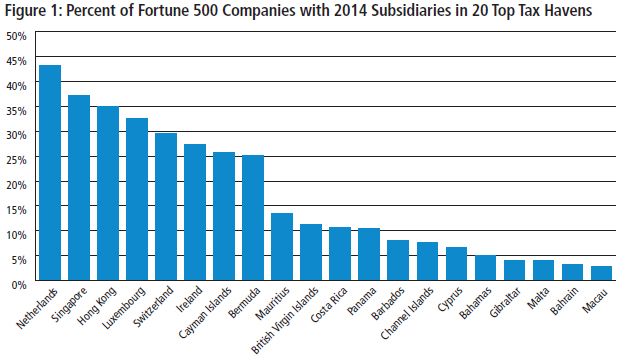

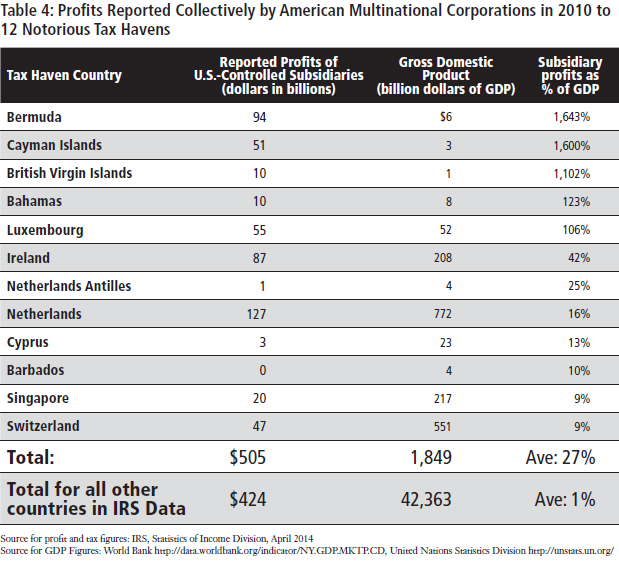

Approximately 60 percent of companies with tax haven subsidiaries have set up at least one in Bermuda or the Cayman Islands — two particularly notorious tax havens. Furthermore, the profits that all American multinationals — not just Fortune 500 companies — collectively claimed they earned in these two island nations in 2010 totaled 1,643 percent and 1,600 percent of each country’s entire yearly economic output, respectively.

Fortune 500 companies are holding more than $2.1 trillion in accumulated profits offshore for tax purposes. Just 30 Fortune 500 companies account for 65 percent of these offshore profits. These 30 companies with the most money offshore have booked $1.4 trillion overseas for tax purposes.

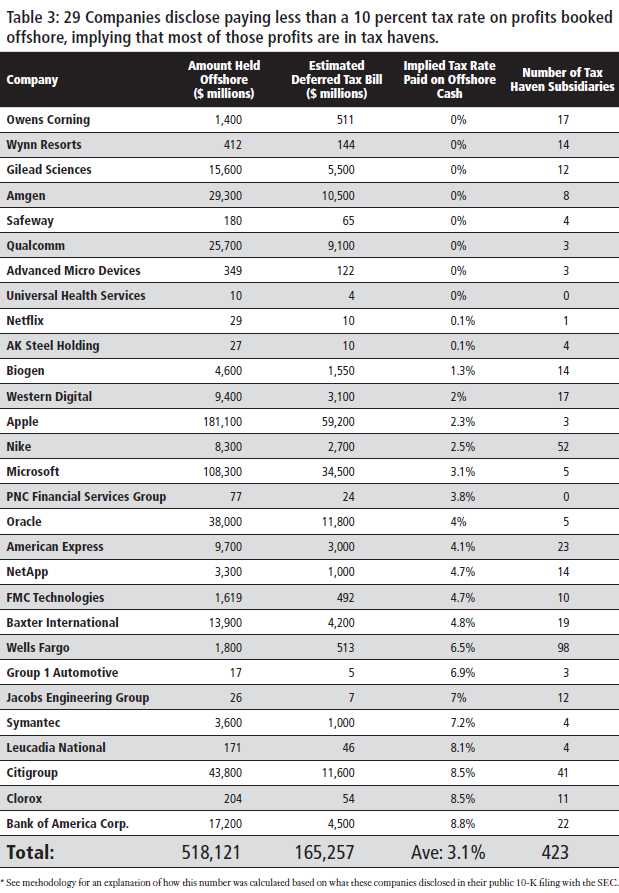

Only 57 Fortune 500 companies disclose what they would expect to pay in U.S. taxes if these profits were not officially booked offshore. In total, these 57 companies would owe $184.4 billion in additional federal taxes. Based on these 57 corporations’ public disclosures, the average tax rate that they have collectively paid to foreign countries on these profits is a mere 6.0 percent, indicating that a large portion of this offshore money has been booked in tax havens. If we apply that average tax rate of 6.0 percent to the entirety of Fortune 500 companies, they would collectively owe $620 billion in additional federal taxes. Some of the worst offenders include:

–Apple: Apple has booked $181.1 billion offshore — more than any other company. It would owe $59.2 billion in U.S. taxes if these profits were not officially held offshore for tax purposes. A 2013 Senate investigation found that Apple has structured two Irish subsidiaries to be tax residents of neither the United States, where they are managed and controlled, nor Ireland, where they are incorporated. This arrangement ensures that they pay no tax to any government on the lion’s share of their offshore profits.

–American Express: The credit card company officially reports $9.7 billion offshore for tax purposes on which it would owe $3 billion in U.S. taxes. That implies that American Express currently has paid only a 4 percent tax rate on its offshore profits to foreign governments, indicating that most of the money is booked in tax havens levying little to no tax. American Express maintains 23 subsidiaries in offshore tax havens.

–Nike: The sneaker giant officially holds $8.3 billion offshore for tax purposes on which it would owe $2.7 billion in U.S. taxes. This implies Nike pays a mere 2.5 percent tax rate to foreign governments on those offshore profits, indicating that nearly all of the money is officially held by subsidiaries in tax havens. Nike likely does this in part by licensing the trademarks for some of its products to three subsidiaries in Bermuda to which it then pays royalties (essentially to itself).

Some companies that report a significant amount of money offshore maintain hundreds of subsidiaries in tax havens, including the following:

–PepsiCo maintains 132 subsidiaries in offshore tax havens. The soft drink maker reports holding $37.8 billion offshore for tax purposes, though it does not disclose what its estimated tax bill would be if it didn’t book those profits offshore.

–Pfizer, the world’s largest drug maker, operates 151 subsidiaries in tax havens and officially holds $74 billion in profits offshore for tax purposes, the fourth highest among the Fortune 500. Pfizer recently attempted the acquisition of a smaller foreign competitor so it could reincorporate on paper as a “foreign company.” Pulling this off would have allowed the company a tax-free way to use its supposedly offshore profits in the U.S.

–Morgan Stanley reports having 210 subsidiaries in offshore tax havens. The bank officially holds $7.4 billion offshore. It has also been infamously implicated in facilitating individual tax evasion through its Swiss banking division.

Corporations that disclose fewer tax haven subsidiaries do not necessarily dodge taxes less. Many companies have disclosed fewer tax haven subsidiaries in recent years, all while increasing the amount of cash they keep offshore. Some companies may simply be failing to disclose substantial numbers of tax haven subsidiaries. Others may be booking larger amounts of income to fewer tax haven subsidiaries.

Consider:

–Citigroup reported operating 427 tax haven subsidiaries in 2008 but disclosed only 41 in 2014. Over that time period, Citigroup nearly doubled the amount of cash it reported holding offshore. The company currently pays only an 8.5 percent tax rate offshore, implying that most of those profits have been booked to low- or no-tax jurisdictions.

–Walmart reported operating zero tax haven subsidiaries in 2014 and for the past decade. Despite this, a recent report released by Americans for Tax Fairness revealed that the company operates as many as 75 tax haven subsidiaries (using this report’s list of tax haven countries) that were not included in its SEC filings. Over the past decade, Walmart’s offshore income has grown from $6.8 billion in 2005 to $23.3 billion in 2014.

–Bank of America reported operating 264 tax haven subsidiaries in 2013 but disclosed only 22 in 2014. At the same time, Bank of America’s offshore holdings have increased modestly from $17 billion to $17.2 billion.

–Google reported operating 25 subsidiaries in tax havens in 2009, but since 2010 only discloses two, both in Ireland. During that period, it increased the amount of cash it reported offshore from $7.7 billion to $47.4 billion. An academic analysis found that as of 2012, the 23 no-longer-disclosed tax haven subsidiaries were still operating.

–Microsoft, which reported operating 10 subsidiaries in tax havens in 2007, disclosed only five in 2014. During this same time period, the amount of money that Microsoft reported holding offshore jumped by a factor of 14. Microsoft has paid a tax rate of only 3 percent to foreign governments on those profits, suggesting that most of the cash is booked in tax havens.

Congress can and should take strong action to prevent corporations from using offshore tax havens, which in turn would restore basic fairness to the tax system, reduce the deficit and improve the functioning of markets.

There are clear policy solutions that lawmakers can enact to crack down on tax haven abuse. They should end the incentives for companies to shift profits offshore, close the most egregious offshore loopholes and increase transparency.

Introduction

There is no greater symbol of the excesses of the world of corporate tax havens than the Ugland house, a modest five-story office building in the Cayman Islands that serves as the registered address for 18,857 companies.[i] Simply by registering subsidiaries in the Cayman Islands, U.S. companies can use legal accounting gimmicks to make much of their U.S.-earned profits appear to be earned in the Caymans and thus pay no taxes on those profits.

U.S. law does not even require that subsidiaries have any physical presence in the Caymans beyond a post office box. In fact, about half of the subsidiaries registered at the infamous Ugland have their billing address in the U.S., even while they are officially registered in the Caymans.[ii] This unabashedly false corporate “presence” is one of the hallmarks of a tax haven subsidiary.

|

What is a Tax Haven? Tax havens have four identifying features.[iii] This study uses a list of 50 tax haven |

Companies can avoid paying taxes by booking profits to a tax haven because U.S. tax laws allow them to defer paying U.S. taxes on profits that they report are earned abroad until they ”repatriate” the money to the United States. Many U.S. companies game this system by using loopholes that allow them to disguise profits actually made in the U.S. as “foreign” profits earned by subsidiaries in a tax haven.

Offshore accounting gimmicks by multinational corporations have created a disconnect between where companies locate their actual workforce and investments, on one hand, and where they claim to have earned profits, on the other. The Congressional Research Service found that in 2008, American multinational companies collectively reported 43 percent of their foreign earnings in five small tax haven countries: Bermuda, Ireland, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, and Switzerland. Yet these countries accounted for only 4 percent of the companies’ foreign workforces and just 7 percent of their foreign investments. By contrast, American multinationals reported earning just 14 percent of their profits in major U.S. trading partners with higher taxes — Australia, Canada, the UK, Germany, and Mexico — which accounted for 40 percent of their foreign workforce and 34 percent of their foreign investment.[v] The IRS released data last year showing that American multinationals collectively reported in 2010 that 54 percent of their foreign earnings were “earned” in 12 notorious tax havens (see table 4).[vi]

Profits booked “offshore” often remain onshore, invested in U.S. assets.

Much if not most of the profits kept “offshore” are actually housed in U.S. banks or invested in American assets, but are registered in the name of foreign subsidiaries. In such cases, American corporations benefit from the stability of the U.S. financial system while avoiding paying taxes on their profits that officially remain booked “offshore” for tax purposes.[vii] A Senate investigation of 27 large multinationals with substantial amounts of cash that was supposedly “trapped” offshore found instead that more than half of the offshore funds were already invested in U.S. banks, bonds, and other assets.[viii] For some companies the percentage is much higher. A Wall Street Journal investigation found that 93 percent of the money Microsoft has officially booked “offshore” is invested in U.S. assets.[ix] In theory, companies are barred from investing directly in their U.S. operations, paying dividends to shareholders or repurchasing stock with money they declare to be “offshore.” But even that restriction is easily evaded because companies can use the cash supposedly “trapped” offshore for those purposes by borrowing at negligible rates using their offshore holdings as implied collateral.

Average Taxpayers Pick Up the Tab for Offshore Tax Dodging.

Congress has created loopholes in our tax code that allow offshore tax avoidance, which forces ordinary Americans to make up the difference. The practice of shifting corporate income to tax haven subsidiaries reduces federal revenue by an estimated $90 billion annually.[x] Every dollar in taxes companies avoid by using tax havens must be balanced by higher taxes paid by other Americans, cuts to government programs, or increased federal debt. If small business owners were to pick up the full tab for offshore tax avoidance by multinationals, they would on average each have had to pay an estimated $3,244 in additional taxes last year.[xi]

It makes sense for profits earned in America to be subject to U.S. taxation. The profits earned by these companies generally depend on access to America’s largest-in-the-world consumer market, a well-educated workforce trained by our school systems, strong private-property rights enforced by our court system, and American roads and rail to bring products to market.[xii] Multinational companies that depend on America’s economic and social infrastructure are shirking their obligation to pay for that infrastructure when they shelter their profits overseas.

|

A NOTE ON MISLEADING TERMINOLOGY “Offshore profits”: Using the term “offshore profits” “Repatriation” or “bringing the money back”: |

Most of America’s Largest Corporations Maintain Subsidiaries in Offshore Tax Havens

This study found that as of 2014, 358 of Fortune 500 companies — nearly three-quarters — disclose subsidiaries in offshore tax havens, indicating how pervasive tax haven use is among large companies. All told, these 358 companies maintain at least 7,622 tax haven subsidiaries.[xiii] The 30 companies with the most money held offshore collectively disclose 1,225 tax haven subsidiaries. Bank of America, Citigroup, JPMorgan-Chase, Goldman Sachs, Wells Fargo and Morgan Stanley — all large financial institutions that received taxpayer bailouts in 2008 — disclose a combined 412 subsidiaries in tax havens.

Companies that rank high for both the number of tax haven subsidiaries and how much profit they book offshore for tax purposes include:

–PepsiCo maintains 132 subsidiaries in offshore tax havens. The soft drink maker reports holding $37.8 billion offshore for tax purposes, though it does not disclose what its estimated tax bill would be if it didn’t keep those profits offshore.

–Pfizer, the world’s largest drug maker, operates 151 subsidiaries in tax havens and officially $74 billion in profits offshore for tax purposes, the fourth highest among the Fortune 500. The company made more than 41 percent of its sales in the U.S. between 2008 and 2014,[xiv] but managed to report no federal taxable income for seven years in a row. This is because Pfizer uses accounting techniques to shift the location of its taxable profits offshore. For example, the company can transfer patents for its drugs to a subsidiary in a low- or no-tax country. Then when the U.S. branch of Pfizer sells the drug in the U.S., it “pays” its own offshore subsidiary high licensing fees that turn domestic profits into on-the-books losses and shifts profit overseas.

Pfizer recently attempted a corporate “inversion” in which it would have acquired a smaller foreign competitor so it could reincorporate on paper in the United Kingdom and no longer be an American company. A key reason Pfizer attempted this maneuver was to make it even easier to shift U.S. profits offshore and have full use of their offshore cash without paying taxes on them.

–Morgan Stanley reports having 210 subsidiaries in offshore tax havens. The bank officially holds $7.4 billion offshore. It has also been infamously implicated in facilitating individual tax evasion through its Swiss banking division.

Cash Booked Offshore for Tax Purposes by U.S. Multinationals Doubled between 2008 and 2014

In recent years, U.S. multinational companies have sharply increased the amount of money that they book to foreign subsidiaries. An April 2015 study by research firm Audit Analytics found that the Russell 1000 list of U.S. companies collectively reported having nearly $2.3 trillion held offshore. That is more than double the income reported offshore in 2008.[xv]

For many companies, increasing profits held offshore does not mean building factories abroad, selling more products to foreign customers, or doing any additional real business activity in other countries. Instead, many companies use accounting tricks to disguise their profits as “foreign,” and book them to a subsidiary in a tax haven to avoid taxes.

The practice of artificially shifting profits to tax havens has increased in recent years. In 1999, the profits American multinationals reported earning in Bermuda represented 260 percent of that country’s entire economy. In 2008, it was up to 1,000 percent.[xvi] More offshore profit shifting means more U.S. taxes avoided by American multinationals. A 2007 study by tax expert Kimberly Clausing of Reed College estimated that the revenue lost to the Treasury due to offshore tax haven abuse by corporations totaled $60 billion annually. In 2011, she updated her estimate to $90 billion.[xvii]

The 286 Fortune 500 Companies that report offshore profits collectively hold $2.1 trillion offshore, with 30 companies accounting for 65 percent of the total.

By the end of 2014, the 286 Fortune 500 companies that report holding offshore cash had collectively accumulated over $2.1 trillion that they declare to be “permanently reinvested” abroad. (This designation allows them to avoid counting the taxes they have “deferred” as a future cost in their financial reports to shareholders.) While 57 percent of Fortune 500 companies report having income offshore, some companies shift profits offshore far more aggressively than others. The 30 companies with the most money offshore account for $1.4 trillion of the total. In other words, just 30 Fortune 500 companies account for 65 percent of the offshore cash.

Not all companies report how much cash they have “permanently reinvested offshore,” so the finding that 286 companies report offshore profits does not include all cash booked offshore. For example, Northrop Grumman reported in 2011 having $761 million offshore. But since 2012, the defense contractor has reported that it continues to have permanently reinvested earnings, but no longer specifies how much.

Evidence Indicates Much of Offshore Profits are Booked to Tax Havens

Companies are not required to disclose publicly how much they tell the I.R.S. they’ve earned in specific foreign countries. Still, some companies provide enough information in their annual SEC filings to deduce that these companies characterize for tax purposes that much of their offshore cash is sitting in tax havens.

Only 57 Fortune 500 companies disclose what they would pay in taxes if they did not book their profits offshore.

In theory, companies are required to disclose how much they would owe in taxes on their offshore profits in their annual 10-K filings to the SEC and shareholders. But a major loophole allows them to avoid such disclosure if the company claims that it is “not practicable” to calculate the tax.[xviii] The 57 companies that do publicly disclose the tax calculations report that they would owe $184.4 billion in additional federal taxes, a tax rate of 29 percent.

The U.S. tax code allows a credit for taxes paid to foreign governments when profits held offshore are declared in the U.S. and become taxable here. While the U.S. corporate tax rate is 35 percent, the average tax rate that these 57 companies have paid to foreign governments on the profits they’ve booked offshore appears to be a mere 6 percent.[xix] That in turn indicates that the bulk of their offshore cash has been booked in tax havens that levy little or no corporate tax.

If the additional 29.0 percent tax rate that the 57 disclosing companies say they would owe would also apply to the offshore cash held by the non-disclosing companies, then the Fortune 500 companies as a group would owe an additional $620 billion in federal taxes.

Examples of large companies paying very low foreign tax rates on offshore cash include:

–Apple: Apple has booked $181.1 billion offshore — more than any other company. It would owe $59.2 billion in U.S. taxes if these profits were not officially held offshore for tax purposes. This means that Apple has paid a miniscule 2.3 percent tax rate on its offshore profits. That confirms that Apple has been getting away with paying almost nothing in taxes on the huge amount of profits it has booked in Ireland.

–American Express: This company reports $9.7 billion in accumulated offshore profits, on which it says it would owe $3 billion in U.S. taxes. That implies that it has paid only a 4 percent tax rate to foreign governments on its offshore profits, and thus indicates that most of that money has been booked in tax havens levying little to no tax.[xx] American Express maintains 23 subsidiaries in offshore tax havens.

–Nike: The sneaker giant reports $8.3 billion in accumulated offshore profits, on which it would owe $2.7 billion in U.S. taxes. That implies Nike has paid a mere 2.5 percent tax rate to foreign governments on those offshore profits. Again, this indicates that nearly all of the offshore money is held by subsidiaries in tax havens. Nike is likely able to engage in such tax avoidance in part by transferring the ownership of Nike trademarks for some of its products to 3 subsidiaries in Bermuda. Humorously, Nike’s Bermuda subsidiaries bear the names of Nike shoes such as “Air Max Limited” and “Nike Flight.”[xxi]

The latest IRS data show that in 2010, more than half of the foreign profits reported by all U.S. multinationals were booked in tax havens for tax purposes.

In the aggregate, IRS data show that in 2010, American multinationals collectively reported to the IRS that they earned $505 billion in 12 well known tax havens. That’s more than half (54 percent) of the total profits that American companies reported earning abroad that year. For the five tax havens where American companies booked the most profits, those reported earnings were greater than the size of those countries’ entire economies (as measured by GDP). This illustrates how little relationship there is between where American multinationals actually do business and where they report that they made their profits for tax purposes.

Approximately 65 percent of companies with tax haven subsidiaries have registered at least one subsidiary in Bermuda or the Cayman Islands — the two tax havens where profits from American multinationals accounted for the largest percentage of the two countries’ GDP.

|

Maximizing the benefit of offshore tax havens by reincorporating as a “foreign” company: a new wave of corporate “inversions.” Some American companies have gone so far as to change the address of their corporate headquarters, on paper, so they can reincorporate in a foreign country, a maneuver called an ‘inversion.” Inversions increase the reward for exploiting offshore loopholes. In theory, an American company must pay U.S. tax on profits it claims were made offshore if it wants to officially bring the money back to the U.S. to pay out dividends to shareholders or make certain U.S. investments. However, this scheme stands reality on its head. Once a corporation reconfigures itself as “foreign,” the profits it claims were earned for tax purposes outside the U.S. become exempt from U.S. tax. Even though a “foreign” corporation still is supposed to pay U.S. tax on profits it earns in the U.S., corporate inversions are often followed by “earnings-stripping.” This is a scheme in which a corporation loads the American part of the company with debt owed to the foreign part of the company. The interest payments on the debt are tax deductible, thus reducing taxable American profits. The foreign company to which the U.S. profits are shifted will be set up in a tax haven to avoid foreign taxes as well.[xxii] In 2004, Congress passed bipartisan legislation to crack down on inversions. The law now requires that inverted companies that have at least 80 percent of the same shareholders as the pre-inversion parent to be treated as American companies for tax purposes, unless the company did “substantial business” in the country in which it was reincorporating.[xxiii] The Treasury’s definition of “substantial business” made this law difficult to game.[xxiv] However, in recent years, companies have discovered a way to circumvent the bipartisan anti-inversion laws. They do so by acquiring a smaller foreign company so that shareholders of the foreign company own slightly more than 20 percent of the newly merged company.[xxv] Walgreens and Pfizer — two quintessentially American companies — made headlines when it was revealed that they were considering mergers that would allow them to reincorporate abroad. A Bloomberg investigation found that 15 publicly traded companies have reincorporated abroad within the last few years, explaining that “most of their CEOs didn’t leave. Just the tax bills did.”[xxvi] |

Firms Reporting Fewer Tax Haven Subsidiaries Do Not Necessarily Dodge Fewer Taxes Offshore

In 2008, the Government Accountability Office conducted a study revealing 83 of the top 100 publicly traded companies operated subsidiaries in offshore tax havens. But more tax haven subsidiaries doesn’t necessarily mean that a company dodges more taxes than other companies. Today, some companies report fewer subsidiaries in tax haven countries than they did in 2008, but some of these same companies report significant increases in how much cash they hold abroad. They report paying such low tax rates to foreign governments that it indicates most if not all of the money has been booked in tax havens.

One explanation for this phenomenon is that some companies are simply not reporting some of the offshore subsidiaries that they previously disclosed. The SEC requires that companies report all “significant” subsidiaries, based on multiple measures of a subsidiary’s share of the company’s total assets. Furthermore, if the combined assets of all subsidiaries deemed “insignificant” collectively qualified as a significant subsidiary, then the company would have to disclose them. But a recent academic study found that the penalties for not disclosing subsidiaries are so light that companies might decide that disclosure isn’t worth the bad publicity it could engender. The researchers postulate that increased media attention on offshore tax dodging and/or IRS scrutiny could be a reason why some companies have stopped disclosing all of their offshore subsidiaries. Examining the case of Google, the academics found that it was so improbable that the company could only have two significant foreign subsidiaries that Google “may have calculated that the SEC’s failure-to-disclose penalties are largely irrelevant and therefore may have determined that disclosure was not worth the potential costs associated with increases in either tax and/or negative publicity costs.”[xxvii] Moreover, the researchers found that as of 2012, 23 of Google’s no-longer-disclosed tax haven subsidiaries were still operating.

Another possibility is that companies are simply consolidating more income in fewer offshore subsidiaries, since having just one tax haven subsidiary is enough to dodge billions in taxes. For example, a 2013 Senate investigation of Apple found that the tech giant primarily uses two Irish subsidiaries — which own the rights to some of Apple’s intellectual property — to hold $102 billion in offshore cash. Manipulating tax loopholes in the U.S. and other countries, Apple has structured these subsidiaries so that they are not tax residents of either the U.S. or Ireland, ensuring that they pay no taxes to any government on the lion’s share of the money. One of the subsidiaries has no employees.[xxviii]

Examples of large companies that have reported fewer tax haven subsidiaries in recent years while simultaneously shifting more profits offshore include:

–Citigroup reported operating 427 tax haven subsidiaries in 2008 but disclosed only 41 in 2014. Over that time period, Citigroup increased the amount of cash it reported holding offshore from $21.1 billion to $43.8 billion, ranking the company 12th for the amount of cash booked offshore. The company estimates it would owe $11.6 billion in taxes had it not booked those profits offshore. The company currently pays an 8.5 percent tax rate offshore, implying that most of those profits have been booked to low- or no-tax jurisdictions.

–Walmart reported operating zero tax haven subsidiaries in 2014 and for the past decade. Despite this, a recent report released by Americans for Tax Fairness revealed that the company had as many as 75 tax haven subsidiaries (using this report’s list of tax haven countries) in operation that were not included in its SEC filings.[xxix] Over the past decade, Walmart’s accumulated offshore profits have grown from $6.8 billion in 2005 to $23.3 billion in 2014.

–Bank of America reported operating 264 tax haven subsidiaries in 2013, but disclosed only 22 in 2014. At the same time, Bank of America’s offshore holdings have increased modestly, from $17 billion to $17.2 billion.

–Google reported operating 25 subsidiaries in tax havens in 2009, but since 2010 it has only disclosed two, both in Ireland. During that period, it increased the amount of profits it has booked offshore from $7.7 billion to $47.4 billion. As noted above, an academic analysis found that as of 2012, the 23 no-longer-disclosed tax haven subsidiaries were still operating.[xxx] Google uses accounting techniques nicknamed the “double Irish” and the “Dutch sandwich,” according to a Bloomberg investigation. Using two Irish subsidiaries, one of which is headquartered in Bermuda, Google shifts profits through Ireland and the Netherlands to Bermuda, shrinking its tax bill by approximately $2 billion a year.[xxxi]

–Microsoft reported operating 10 subsidiaries in tax havens in 2007; in 2014, it disclosed only five. During this same time period, the company increased the amount of money it held offshore from $7.5 billion to $108.3 billion, on which it says it would owe $34.5 billion in U.S. taxes. That implies that the company has paid a tax rate of just 3 percent to foreign governments on those profits, indicating that most of the cash is booked to tax havens. Microsoft ranks 3rd for the amount of cash it keeps offshore. A Wall Street Journal investigation found that over 90 percent of Microsoft “offshore” cash was actually invested by its offshore subsidiaries in U.S. assets like Treasuries, allowing for the company to benefit from the stability of the U.S. financial system without paying taxes on those profits.[xxxii]

Measures to Stop Abuse of Offshore Tax Havens

Strong action to prevent corporations from using offshore tax havens will not only restore basic fairness to the tax system, but will also alleviate pressure on America’s budget deficit and improve the functioning of markets. Markets work best when companies thrive based on their innovation or productivity, rather than the aggressiveness of their tax accounting schemes.

Policymakers should reform the corporate tax code to end the incentives that encourage companies to use tax havens, close the most egregious loopholes, and increase transparency so companies can’t use layers of shell companies to shrink their taxes.

End incentives to shift profits and jobs offshore.

-The most comprehensive solution to ending tax haven abuse would be to stop permitting U.S. multinational corporations to indefinitely defer paying U.S. taxes on profits they attribute to their foreign subsidiaries. In other words, companies should pay taxes on their foreign income at the same rate and time that they pay them on their domestic income. Paying U.S. taxes on this overseas income would not constitute “double taxation” because the companies already subtract any foreign taxes they’ve paid from their U.S. tax bill, and that would not change. Ending “deferral” could raise nearly $900 billion over ten years, according to the both the Congressional Joint Committee on Taxation and the U.S. Treasury Department.[xxxiii]

-The best way to deal with existing profits being held offshore would be to tax them through a deemed repatriation at the full 35 percent rate (minus foreign taxes paid). President Obama has proposed a much lower rate of 14 percent, which would allow large multinational corporations to avoid around $400 billion in taxes that they owe. Former Republican Ways and Means Chairman Dave Camp proposed a rate of only 8.75 percent, which would allow large multinational corporations to avoid around $450 billion in taxes that they owe. At a time of fiscal austerity, there is no reason that companies should get hundreds of billions in tax benefits to reward them for their offshore income.

Reject the Creation of New Loopholes

-Reject a “territorial” tax system. Tax haven abuse would be worse under a system in which companies could shift profits to tax haven countries, pay minimal or no tax under those countries’ tax laws, and then freely use the profits in the United States without paying any U.S. taxes. The JCT estimates that switching to a territorial tax system could add almost $300 billion to the deficit over ten years.[xxxiv]

-Reject the creation of a so-called ”innovation” or “patent box.” Some lawmakers are trying to create a new loophole in the code by giving companies a preferential tax rate on income earned from patents, trademarks, and other “intellectual property” which is easy to assign to offshore subsidiaries. Such a policy would be an unjustified and ineffective giveaway to multinational U.S. corporations.[xxxv]

Close the most egregious offshore loopholes.

Policy makers can take some basic common-sense steps to curtail some of the most obvious and brazen ways that some companies abuse offshore tax havens.

-Cooperate with the OECD and its member countries to implement the recommendations of the group’s Base Erosion and Profit Shifting (BEPS) project, which represents a modest first step toward international coordination to end corporate tax avoidance.[xxxvi]

-Close the inversion loophole by treating an entity that results from a U.S.-foreign merger as an American corporation if the majority (as opposed to 80 percent) of voting stock is held by shareholders of the former American corporation. These companies should be treated as U.S. companies if they are managed and controlled in the U.S. and have significant business activities in the U.S.[xxxvii]

-Stop companies from shifting intellectual property (e.g. patents, trademarks, licenses) to shell companies in tax haven countries and then paying inflated fees to use them. This common practice allows companies to legally book profits that were earned in the U.S. to the tax haven subsidiary owning the patent. Limited reforms proposed by President Obama could save taxpayers $21.3 billion over ten years, according to the Joint Committee on Taxation (JCT).[xxxviii]

-Reform the so-called “check-the-box” rules to stop multinational companies from manipulating how they define their status to minimize their taxes. Right now, companies can make inconsistent claims to maximize their tax advantages, telling one country that a subsidiary is a corporation while telling another country the same entity is a partnership or some other form.

-Stop companies from taking bigger tax credits than the law intends for the taxes they pay to foreign countries by reforming foreign tax credits. Proposals to “pool” foreign tax credits would save $58.6 billion over ten years, according to the JCT.[xxxix]

-Stop companies from deducting interest expenses paid to their own offshore affiliates, which put off paying taxes on that income. Right now, an offshore subsidiary of a U.S. company can defer paying taxes on interest income it collects from the U.S.-based parent, even while the U.S. parent claims those interest payments as a tax deduction. This reform would save $51.4 billion over ten years, according to the JCT.[xl]

Increase transparency.

-Require full and honest reporting to expose tax haven abuses. Multinational corporations should report their profits on a country-by-country basis so they can’t mislead each nation about the share of their income that was taxed in the other countries. An annual survey of CEOs around the globe done by PricewaterhouseCoopers found that nearly 60 percent of the CEOs support this reform as a way to clamp down on avoidance.[xli]

Methodology

To calculate the number of tax haven subsidiaries maintained by the Fortune 500 corporations, we used the same methodology as a 2008 study by the Government Accountability Office that used 2007 data (see endnote 5).

The list of 50 tax havens used is based on lists compiled by three sources using similar characteristics to define tax havens. These sources were the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), the National Bureau of Economic Research, and a U.S. District Court order. This court order gave the IRS the authority to issue a “John Doe” summons, which included a list of tax havens and financial privacy jurisdictions.

The companies surveyed make up the 2015 Fortune 500, a list of which can be found here: http://money.cnn.com/magazines/fortune/fortune500/.

To figure out how many subsidiaries each company had in the 50 known tax havens, we looked at “Exhibit 21” of each company’s 2014 10-K report, which is filed annually with the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC). Exhibit 21 lists out every reported subsidiary of the company and the country in which it is registered. We used the SEC’s EDGAR database to find the 10-K filings. 358 of the Fortune companies disclose offshore subsidiaries, but it is possible that many of the remaining 142 companies simply do not disclose their offshore tax haven subsidiaries.

We also used 10-K reports to find the amount of money each company reported it kept offshore in 2014. This information is typically found in the tax footnote of the 10-K. The companies disclose this information as the amount they keep “permanently reinvested” abroad.

As explained in this report, 57 of the companies surveyed disclosed what their estimated tax bill would be if they repatriated the money they kept offshore. This information is also found in the tax footnote. To calculate the tax rate these companies paid abroad in 2014, we first divided the estimated tax bill by the total amount kept offshore. That number multiplied by 100 equals the U.S. tax rate the company would pay if they repatriated that foreign cash. Since companies receive dollar-for-dollar credits for taxes paid to foreign governments, the tax rate paid abroad is simply the difference between 35% — the U.S. statutory corporate tax rate — and the tax rate paid upon repatriation.

End Notes

[i] Government Accountability Office, Business and Tax Advantages Attract U.S. Persons and Enforcement Challenges Exist, GAO-08-778, a report to the Chairman and Ranking Member, Committee on Finance, U.S. Senate, July 2008, http://www.gao.gov/highlights/d08778high.pdf.

[ii] Id.

[iii] Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, “Harmful Tax Competition: An Emerging Global Issue,” 1998. http://www.oecd.org/tax/transparency/44430243.pdf

[iv] Government Accountability Office, International Taxation; Large U.S. Corporations and Federal Contractors with Subsidiaries in Jurisdictions Listed as Tax Havens or Financial Privacy Jurisdictions, December 2008.

[v] Mark P. Keightley, Congressional Research Service, An Analysis of Where American Companies Report Profits: Indications of Profit Shifting, 18 January, 2013.

[vi] Citizens for Tax Justice, American Corporations Report Over Half of Their Offshore Profits as Earned in 12 Tax Havens, 28 May 2014.

[vii] Kitty Richards and John Craig, Offshore Corporate Profits: The Only Thing ‘Trapped’ Is Tax Revenue, Center for American Progress, 9 January, 2014, http://www.americanprogress.org/issues/tax-reform/report/2014/01/09/81681/offshore-corporate-profits-the-only-thing-trapped-is-tax-revenue/.

[viii] Offshore Funds Located On Shore, Majority Staff Report Addendum, Senate Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations, 14 December 2011, http://www.levin.senate.gov/newsroom/press/release/new-data-show-corporate-offshore-funds-not-trapped-abroad-nearly-half-of-so-called-offshore-funds-already-in-the-united-states/.

[ix] Kate Linebaugh, “Firms Keep Stockpiles of ‘Foreign’ Cash in U.S.,” Wall Street Journal, 22 January 2013, http://online.wsj.com/article/SB10001424127887323284104578255663224471212.html.

[x] Kimberly A. Clausing, “The Revenue Effects of Multinational Firm Income Shifting,” Tax Notes, 28 March 2011, 1560-1566.

[xi] Dan Smith and Jaimie Woo. Picking up the Tab, U.S. PIRG, April 2015. http://www.uspirg.org/reports/usp/picking-tab-2015-small-businesses-pay-price-offshore-tax-havens.

[xii] “China to Become World’s Second Largest Consumer Market”, Proactive Investors United Kingdom, 19 January, 2011 (Discussing a report released by Boston Consulting Group), http://www.proactiveinvestors.co.uk/columns/china-weekly-bulletin/4321/china-to-become-worlds-second-largest-consumer-market-4321.html.

[xiii] The number of subsidiaries registered in tax havens is calculated by authors looking at exhibit 21 of the company’s 2013 10-K report filed annually with the Securities and Exchange Commission. The list of tax havens comes from the Government Accountability Office report cited in note 5.

[xiv] Calculated by the authors based on revenue information from Pfizer’s 2014 10-K filing.

[xv] Audit Analytics, “Untaxed Foreign Earnings top $2.3 Trillion in 2014,” April 2015. http://www.auditanalytics.com/blog/untaxed-foreign-earnings-top-2-3-trillion-in-2014/.

[xvi] See note 6.

[xvii] Kimberly A. Clausing, “Multinational Firm Tax Avoidance and Tax policy,” 62 Nat’l Tax J 703, December 2009; see note 10 for more recent study.

[xviii] Citizens for Tax Justice, “Apple is not Alone” 2 June 2013, http://ctj.org/ctjreports/2013/06/apple_is_not_alone.php#.UeXKWm3FmH8.

[xix] See methodology for an explanation of how this was calculated.

[xx] Companies get a credit for taxes paid to foreign governments when they repatriate foreign earnings. Therefore, if companies disclose what their hypothetical tax bill would be if they repatriated “permanently reinvested” earnings, it is possible to deduce what they are currently paying to foreign governments. For example, if a company discloses that they would need to pay the full statutory 35% tax rate on its offshore cash, it implies that they are currently paying no taxes to foreign governments, which would entitle them to a tax credit that would reduce the 35% rate. This method of calculating foreign tax rates was original used by Citizens for Tax Justice (see note 21).

[xxi] Citizens for Tax Justice, “Nike’s Tax Haven Subsidiaries Are Named After Its Shoe Brands,” 25 July 2013, http://www.ctj.org/taxjusticedigest/archive/2013/07/nikes_tax_haven_subsidiaries_a.php#.U3y0Gijze2J.

[xxii] Citizens for Tax Justice, “The Problem of Corporate Inversions: the Right and Wrong Approaches for Congress,” 14 May 2014, http://ctj.org/ctjreports/2014/05/the_problem_of_corporate_inversions_the_right_and_wrong_approaches_for_congress.php#.U3tavSjze2J.

[xxiii] Other consequences kick in for inversions involving 60‐79.9% of the same shareholders. This law is based on a 2002 bill introduced by Senator Charles Grassley (R-IA) and former Sen. Max Baucus (D-MT). See 26 U.S.C.§7874 (available at

http://codes.lp.findlaw.com/uscode/26/F/80/C/7874/).

[xxiv] Treasury first defined “substantial business” in 2006 with a relatively loose bright line standard. That 2006 standard was replaced in 2009 with a vague facts and circumstances test and an intent to make inverting harder.

Companies got comfortable with that approach too, however, and resumed inverting. On June 7, 2012, Treasury issued new temporary rules creating a difficult-to-evade bright line test. Specifically, the new rules define substantial business as a minimum of 25 percent of an inverting company’s business. That is a hard threshold to meet if the main “business” in country is a post office box. But the rules go further by making the standard hard to game; the 25 percent has to be met in three different ways. Moreover, those measurements must be taken a year before the inversion, so the inversion process itself cannot be manipulated to meet the thresholds. For a more detailed discussion of the history of the interpretations, see Latham & Watkins Client Alert No. 1349, “IRS Tightens Rules on Corporate Expatriations — New Regulations Require High Threshold of Foreign Business Activity” June 12, 2012, http://www.google.com/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=14&ved=0CFsQFjADOAo&url=http%3A%2F%2Fwww.lw.com%2FthoughtLeadership%2FIRSTightensRulesonCorporateExpatriations&ei=fPYmUIe‐

Dca36gG5q4GICg&usg=AFQjCNEMzRNjJYwoJtmyd4VJF‐Dnap_hxA.

[xxv] Citizens for Tax Justice, “The Problem of Corporate Inversions: the Right and Wrong Approaches for Congress,” 14 May 2014. http://ctj.org/ctjreports/2014/05/the_problem_of_corporate_inversions_the_right_and_wrong_approaches_for_congress.php#.U3tavSjze2J.

[xxvi] Zachary R. Mider, “Tax Break ‘Blarney’: U.S. Companies Beat the System with Irish Addresses,” Bloomberg News, 5 May 2014, http://www.bloomberg.com/news/2014-05-04/u-s-firms-with-irish-addresses-criticized-for-the-moves.html.

[xxvii] Jeffrey Gramlich and Janie Whiteaker-Poe, “Disappearing subsidiaries: The Cases of Google and Oracle,” March 2013, Working Paper available at SSRN, http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2229576.

[xxviii] Offshore Profit Shifting and the U.S. Tax Code — Part 2,Senate Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations, 21 May, 2013, http://www.hsgac.senate.gov/subcommittees/investigations/hearings/offshore-profit-shifting-and-the-us-tax-code_-part-2.

[xxix] Americans for Tax Fairness, “The Walmart Web,” 17 June 2015. http://www.americansfortaxfairness.org/files/TheWalmartWeb-June-2015-FINAL.pdf

[xxx] See note 27.

[xxxi] Jesse Drucker, “Google Joins Apple Avoiding Taxes with Stateless Income,” Bloomberg News, 22 May 2013, http://www.bloomberg.com/news/2013-05-22/google-joins-apple-avoiding-taxes-with-stateless-income.html.

[xxxii] See note 14.

[xxxiii] Estimate includes both the cost of “Deferral of income from controlled foreign corporations” and to “Extend the exception under subpart F for active financing income.” “Office of Management and Budget, “Fiscal Year Analytical Perspectives of the U.S. Government,” 2015. https://www.whitehouse.gov/sites/default/files/omb/budget/fy2016/assets/spec.pdf

[xxxiv] Listed as “Deduction for dividends received by domestic corporations from certain foreign corporations.” Joint Committee on Taxation, “Estimated Revenue Effects of the “Tax Reform Act of 2014,” February 26, 2014, https://www.jct.gov/publications.html?func=startdown&id=4562. JCT estimated that the cost of a territorial system would be $212 billion over a decade if the U.S. corporate tax rate were reduced to 25%. That translates to a cost of $297 billion under the current 35% tax rate.

[xxxv] Citizens for Tax Justice, “A Patent Box Would Be a Huge Step Back for Corporate Tax Reform,” June, 4, 2015. https://ctj.sfo2.digitaloceanspaces.com/pdf/patentboxstepback.pdf

[xxxvi] OECD, “BEPS 2015 Final Reports,” October 5, 2015. http://www.oecd.org/tax/beps-2015-final-reports.htm

[xxxvii] Citizens for Tax Justice, “Proposals to Resolves the Crisis of Corporate Inversions,” August 21, 014. https://ctj.sfo2.digitaloceanspaces.com/pdf/inversionsproblemsandsolutions.pdf

[xxxviii]Joint Committee on Taxation, “Estimated Budget Effects of the Revenue Provisions Contained in the President’s Fiscal Year 2015 Budget Proposal,” April 15, 2014, https://www.jct.gov/publications.html?func=startdown&id=4585.

[xxxix]Id.

[xl]Id.

[xli] Cited in Tom Bergin, “CEOs back country-by-country tax reporting — survey,” Reuters, 23 April 2014. http://uk.reuters.com/article/2014/04/23/uk-taxcompanies-idUKBREA3M18I20140423.