June 4, 2014 04:16 PM | Permalink | ![]()

The Use of Offshore Tax Havens by Fortune 500 Companies

Download Dataset/Appendix (XLS)

Most of America’s Largest Corporations Maintain Subsidiaries in Offshore Tax Havens

Cash Booked Offshore for Tax Purposes by U.S. Multinationals Doubled between 2008 and 2013

Evidence Indicates Much of Offshore Profits are Booked to Tax Havens

Firms Reporting Fewer Tax Haven Subsidiaries Do Not Necessarily Dodge Fewer Taxes Offshore

Measures to Stop Abuse of Offshore Tax Havens

Executive Summary

Many large U.S.-based multinational corporations avoid paying U.S. taxes by using accounting tricks to make profits made in America appear to be generated in offshore tax havens—countries with minimal or no taxes. By booking profits to subsidiaries registered in tax havens, multinational corporations are able to avoid an estimated $90 billion in federal income taxes each year. These subsidiaries are often shell companies with few, if any employees, and which engage in little to no real business activity.

Congress has left loopholes in our tax code that allow this tax avoidance, which forces ordinary Americans to make up the difference. Every dollar in taxes that corporations avoid by using tax havens must be balanced by higher taxes on individuals, cuts to public investments and public services, or increased federal debt.

This study examines the use of tax havens by Fortune 500 companies in 2013. It reveals that tax haven use is ubiquitous among America’s largest companies, but a narrow set of companies benefit disproportionately.

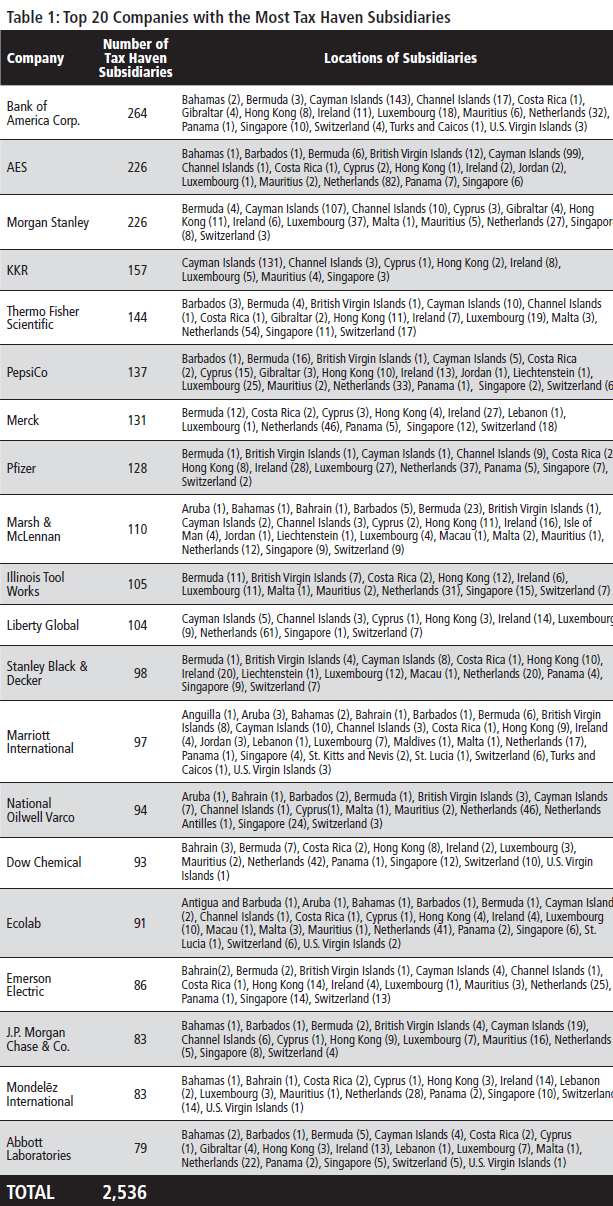

Most of America’s largest corporations maintain subsidiaries in offshore tax havens. At least 362 companies, making up 72 percent of the Fortune 500, operate subsidiaries in tax haven jurisdictions as of 2013.

- All told, these 362 companies maintain at least 7,827 tax haven subsidiaries.

- The 30 companies with the most money officially booked offshore for tax purposes collectively operate 1,357 tax haven subsidiaries.

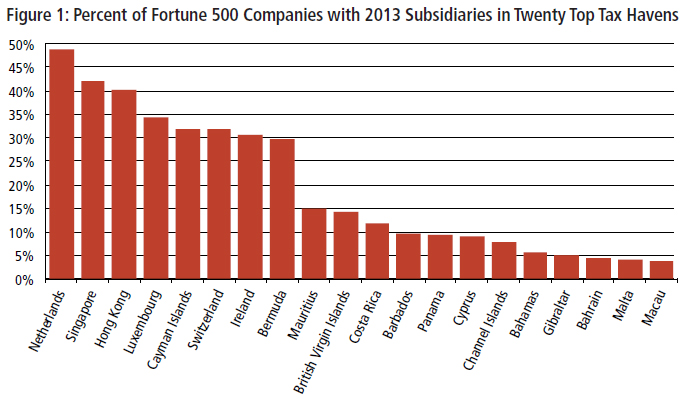

Approximately 64 percent of the companies with any tax haven subsidiaries registered at least one in Bermuda or the Cayman Islands—two notorious tax havens. Furthermore, the profits that all American multinationals—not just Fortune 500 companies—collectively claim were earned in these island nations in 2010 totaled 1,643 percent and 1,600 percent of each country’s entire yearly economic output, respectively.

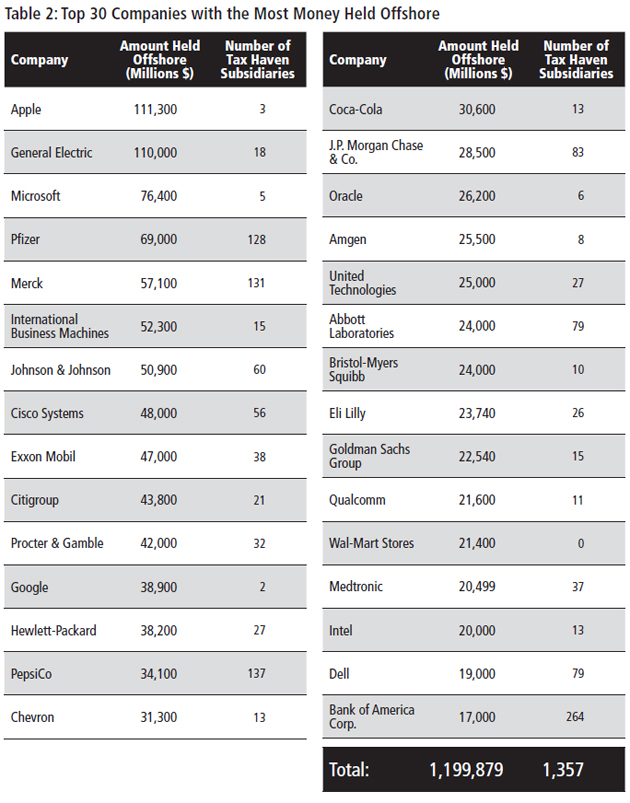

Six percent of Fortune 500 companies account for over 60 percent of the profits reported offshore for tax purposes. These 30 companies with the most money offshore—out of the 287 that report offshore profits—collectively book $1.2 trillion overseas for tax purposes.

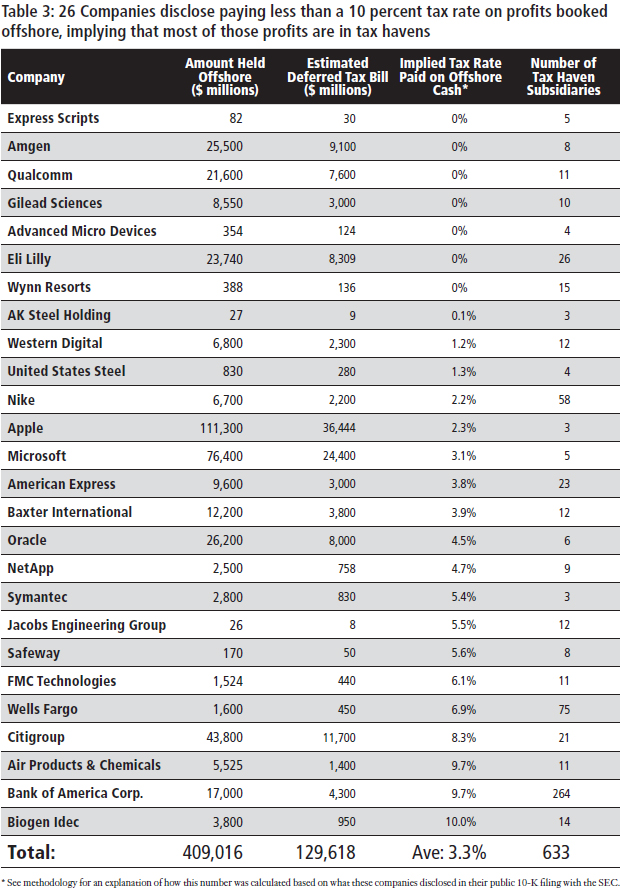

Only 55 Fortune 500 companies disclose what they would expect to pay in U.S. taxes if these profits were not officially booked offshore. All told, these 55 companies would collectively owe $147.5 billion in additional federal taxes. To put this enormous sum in context, it represents more than the entire state budgets of California, Virginia, and Indiana combined. Based on these 55 corporations’ public disclosures, the average tax rate that they have collectively paid to other countries on this income is just 6.7 percent, suggesting that a large portion of this offshore money is booked to tax havens. This list includes:

- Apple: Apple has booked $111.3 billion offshore—more than any other company. It would owe $36.4 billion in U.S. taxes if these profits were not officially held offshore for tax purposes. A 2013 Senate investigation found that Apple has structured two Irish subsidiaries to be tax residents of neither the U.S.—where they are managed and controlled—nor Ireland—where they are incorporated. This arrangement ensures that they pay no taxes to any government on the lion’s share of their offshore profits.

- American Express: The credit card company officially reports $9.6 billion offshore for tax purposes on which it would otherwise owe $3 billion in U.S. taxes. That implies that American Express currently pays only a 3.8 percent tax rate on its offshore profits to foreign governments, suggesting that most of the money is booked in tax havens levying little to no tax. American Express maintains 23 subsidiaries in offshore tax havens.

- Nike: The sneaker giant officially holds $6.7 billion offshore for tax purposes, on which it would otherwise owe $2.2 billion in U.S. taxes. That implies Nike pays a mere 2.2 percent tax rate to foreign governments on those offshore profits, suggesting that nearly all of the money is officially held by subsidiaries in tax havens. Nike does this in part by licensing the trademarks for some of its products to 12 subsidiaries in Bermuda to which it then pays royalties.

Some companies that report a significant amount of money offshore maintain hundreds of subsidiaries in tax havens, including the following:

- Bank of America reports having 264 subsidiaries in offshore tax havens—more than any other company. The bank officially holds $17 billion offshore for tax purposes, on which it would otherwise owe $4.3 billion in U.S. taxes. That means it currently pays a ten percent tax rate to foreign governments on the profits it has booked offshore, implying much of those profits are booked to tax havens.

- PepsiCo maintains 137 subsidiaries in offshore tax havens. The soft drink maker reports holding $34.1 billion offshore for tax purposes, though it does not disclose what its estimated tax bill would be if it didn’t keep those profits booked offshore for tax purposes.

- Pfizer, the world’s largest drug maker, operates 128 subsidiaries in tax havens and officially holds $69 billion in profits offshore for tax purposes, the third highest among the Fortune 500. Pfizer recently attempted the acquisition of a smaller foreign competitor so it could reincorporate on paper as a “foreign company.” Pulling this off would have allowed the company a tax-free way to use its supposedly offshore profits in the U.S.

Corporations that disclose fewer tax haven subsidiaries do not necessarily dodge fewer taxes. Many companies have disclosed fewer tax haven subsidiaries, all the while increasing the amount of cash they keep offshore. For some companies, their actual number of tax haven subsidiaries may be substantially greater

than what they disclose in the official documents used for this study. For others, it suggests that they are booking larger amounts of income to fewer tax haven subsidiaries.

Consider:

- Citigroup reported operating 427 tax haven subsidiaries in 2008 but disclosed only 21 in 2013. Over that time period, Citigroup more than doubled the amount of cash it reported holding offshore. The company currently pays an 8.3 percent tax rate offshore, implying that most of those profits have been booked to low- or no-tax jurisdictions.

- Google reported operating 25 subsidiaries in tax havens in 2009, but since 2010 only discloses two, both in Ireland. During that period, it increased the amount of cash it reported offshore from $7.7 billion to $38.9 billion. An academic analysis found that as of 2012, the 23 no-longer-disclosed tax haven subsidiaries were still operating.

- Microsoft, which reported operating 10 subsidiaries in tax havens in 2007, disclosed only five in 2013. During this same time period, the company increased the amount of money it reported holding offshore by more than 12 times. Microsoft currently pays a tax rate of just 3 percent to foreign governments on those profits, suggesting that most of the cash is booked to tax havens.

Strong action to prevent corporations from using offshore tax havens will restore basic fairness to the tax system, make it easier to avoid large budget deficits, and improve the functioning of markets.

There are clear policy solutions policymakers can enact to crack down on tax haven abuse. Policymakers should end incentives for companies to shift profits offshore, close the most egregious offshore loopholes, and increase transparency.

Introduction

Ugland House is a modest five-story office building in the Cayman Islands, yet it is the registered address for 18,857 companies.1 The Cayman Islands, like many other offshore tax havens, levies no income taxes on companies incorporated there. Simply by registering subsidiaries in the Cayman Islands, U.S. companies can use legal accounting gimmicks to make much of their U.S.-earned profits appear to be earned in the Caymans and pay no taxes on them.

The vast majority of subsidiaries registered at Ugland House have no physical presence in the Caymans other than a post office box. About half of these companies have their billing address in the U.S., even while they are officially registered in the Caymans.2 This unabashedly false corporate “presence” is one of the hallmarks of a tax haven subsidiary.

Companies can avoid paying taxes by booking profits to a tax haven because U.S. tax laws allow them to defer paying U.S. taxes on profits they report are earned abroad until they ”repatriate” the money to the United States. Corporations receive a dollar-for-dollar tax credit for the taxes they pay to foreign governments in order to avoid double taxation. Many U.S. companies game this system by using loopholes that let them disguise profits legitimately made in the U.S. as “foreign” profits earned by a subsidiary in a tax haven.

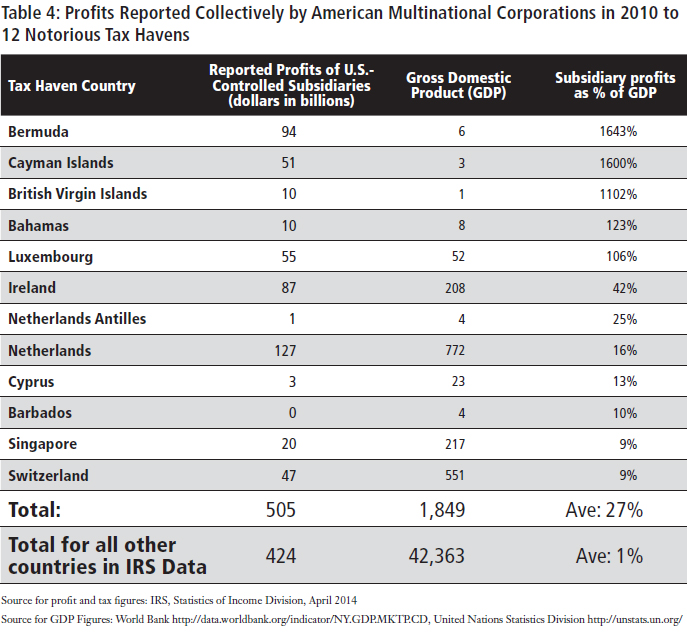

Offshore accounting gimmicks by multinational corporations have created a disconnect between where companies locate their actual workforce and investments, on one hand, and where they claim to have earned profits, on the other. The Congressional Research Service found that in 2008, American multinational companies collectively reported 43 percent of their foreign earnings in five small tax haven countries: Bermuda, Ireland, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, and Switzerland. Yet these countries accounted for only 4 percent of the companies’ foreign workforce and just 7 percent of their foreign investment. By contrast, American multinationals reported earning just 14 percent of their profits in major U.S. trading partners with higher taxes—Australia, Canada, the UK, Germany, and Mexico—which accounted for 40 percent of their foreign workforce and 34 percent of their foreign investment.5 The IRS released data this year showing that American multinationals collectively reported in 2010 that 54 percent of their foreign earnings were on the books in 12 notorious tax havens (see table 4 on pg. 14).6

| What is a Tax Haven?Tax havens are jurisdictions with very low or nonexistent taxes. This makes it attrac-tive for U.S.-based multinational firms to report earnings there to avoid paying taxes in the United States. Most tax haven coun-tries also have financial secrecy laws that can thwart international rules by limit-ing disclosure about financial transactions made in their jurisdiction. These secrecy laws are used by wealthy individuals to avoid paying taxes by setting up offshore shell corporations or trusts. Many tax ha-ven countries are small island nations, such as Bermuda, the British Virgin Islands, and the Cayman Islands.3This study uses a list of 50 tax haven juris-dictions, which each appear on at least one list of tax havens compiled by the Organi-zation for Economic Cooperation and De-velopment (OECD), the National Bureau of Economic Research, or as part of a U.S. District Court order listing tax havens. These lists were also used in a 2008 GAO report investigating tax haven subsidiaries.4

What is a Tax Haven? Tax havens are jurisdictions with very low This study uses a list of 50 tax haven |

Profits booked “offshore” often remain on shore, invested in U.S. assets

Many of the profits kept “offshore” are actually housed in U.S. banks or invested in American assets, but registered in the name of foreign subsidiaries. A Senate investigation of 27 large multinationals with substantial amounts of cash supposedly “trapped” offshore found that more than half of the offshore funds were invested in U.S. banks, bonds, and other assets.7 For some companies the percentage is much higher. A Wall Street Journal investigation found that 93 percent of the money Microsoft has officially “offshore” was invested in U.S. assets.8 In theory, companies are barred from investing directly in their U.S. operations, paying dividends to shareholders or repurchasing stock with money they declare to be “permanently invested offshore.” But even that restriction is easily evaded because companies can use cash supposedly “trapped” offshore for those purposes by borrowing at negligible rates using their offshore holdings as collateral. Either way, American corporations can benefit from the stability of the U.S. financial system without paying taxes on the profits that are officially booked “offshore” for tax purposes.9

Average Taxpayers Pick Up the Tab for Offshore Tax Dodging

Congress has left loopholes in our tax code that allow offshore tax avoidance, which forces ordinary Americans to make up the difference. The practice of shifting corporate income to tax haven subsidiaries reduces federal revenue by an estimated $90 billion annually.10 Every dollar in taxes companies avoid by using tax havens must be balanced by higher taxes paid by other Americans, cuts to government programs, or increased federal debt. If small business owners were to pick up the full tab for offshore tax avoidance by multinationals, they would each have had to pay an estimated $3,206 in additional taxes last year.11

It makes sense for profits earned in America to be subject to U.S. taxation. The profits earned by these companies generally depend on access to America’s largest-in-the-world consumer market, a well-educated workforce trained by our school systems, strong private property rights enforced by our court system, and American roads and rail to bring products to market.12 Multinational companies that depend on America’s economic and social infrastructure are shirking their obligation to pay for that infrastructure if they “shelter” the resulting profits overseas.

|

A Note On Misleading “Offshore profits” Using the term “offshore profits” without “Repatriation” or “bringing the money back” Repatriation is the term used to describe |

Most of America’s Largest Corporations Maintain Subsidiaries in Offshore Tax Havens

This study found that as of 2013, 362 Fortune 500 companies—over 72 percent—disclose subsidiaries in offshore tax havens, indicating how pervasive tax haven use is among large companies. All told, these 362 companies maintain at least 7,827 tax haven subsidiaries.13 The top 30 companies with the most money held offshore collectively disclose 1,357 tax haven subsidiaries. Bank of America, Citigroup, JPMorgan-Chase, AIG, Goldman Sachs, Wells Fargo and Morgan Stanley—all large financial institutions that received taxpayer bailouts in 2008—disclose a combined 702 subsidiaries in tax havens.Cash Booked Offshore

Companies that rank high for both the number of tax haven subsidiaries and how much profit they book offshore for tax purposes include:

- Bank of America, which reports having 264 subsidiaries in offshore tax havens. Kept afloat by taxpayers during the 2008 financial meltdown, the bank reports holding $17 billion offshore, on which it would otherwise owe $4.3 billion in U.S. taxes.14 That implies that it currently pays a ten percent tax rate to foreign governments on the profits it has booked offshore, suggesting much of those profits are booked to tax havens.

- PepsiCo maintains 137 subsidiaries in offshore tax havens. The soft drink maker reports holding $34.1 billion offshore for tax purposes, though it does not disclose what its estimated tax bill would be if it didn’t keep those profits offshore.

- Pfizer, the world’s largest drug maker, operates 128 subsidiaries in tax havens and officially reports $69 billion in profits offshore for tax purposes, the third highest among the Fortune 500.15 The company made more than 40 percent of its sales in the U.S. between 2010 and 2012,16 but managed to report no federal taxable income six years in a row. This is because Pfizer uses accounting techniques to shift the location of its taxable profits offshore. For example, the company can license patents for its drugs to a subsidiary in a low or no-tax country. Then, when the U.S. branch of Pfizer sells the drug in the U.S., it must pay its own offshore subsidiary high licensing fees that turn domestic profits into on-the-books losses and shifts profit overseas.

Pfizer recently attempted a corporate “inversion” in which it would have acquired a smaller foreign competitor so it could reincorporate on paper in the UK and no longer be an American company. A key reason Pfizer attemped this maneuver is that it would have allowed the company to more aggressively shift U.S. profits offshore and have full, unrestricted access to its offshore cash.

Cash Booked Offshore for Tax Purposes by U.S. Multinationals Doubled between 2008 and 2013

Back to Contents

In recent years, U.S. multinational companies have increased the amount of money they book to foreign subsidiaries. An April 2014 study by research firm Audit Analytics found that the Russell 1000 list of U.S. companies collectively reported having just over $2.1 trillion held offshore. That is nearly double the income reported offshore in 2008.17

For many companies, increasing profits held offshore does not mean building factories abroad, selling more products to foreign customers, or doing any additional real business activity in other countries. Instead, many companies use accounting tricks to disguise their profits as “foreign,” and book them to a subsidiary in a tax haven to avoid taxes.

The practice of artificially shifting profits to tax havens has increased in recent years. In 1999, the profits American multinationals reported earning in Bermuda represented 260 percent of the country’s entire economy. In 2008, it was up to 1,000 percent.18 More offshore profit shifting means more U.S. taxes avoided by American multinationals. A 2007 study by tax expert Kimberly Clausing of Reed College estimated that the revenue lost to the Treasury due to offshore tax haven abuse by corporations totaled $60 billion annually. In 2011, she updated her estimate to $90 billion.19

The 287 Fortune 500 Companies that report offshore profits collectively hold $1.95 trillion offshore, with the top 30 companies accounting for 62 percent of the total

This report found that as of 2013, the 287 Fortune 500 companies that report holding offshore cash had collectively accumulated close to $2 trillion that they declare to be “permanently reinvested” abroad. That means they claim to have no current plans to use the money to pay dividends to shareholders, make stock repurchases, or make certain U.S. investments. While 72 percent of Fortune 500 companies report having income offshore, some companies shift profits offshore far more aggressively than others. The thirty companies with the most money offshore account for nearly $1.2 trillion. In other words, six percent of Fortune 500 companies account for 62 percent of the offshore cash.

Not all companies report how much cash they have “permanently reinvested offshore,” so the finding that 287 companies report offshore profits does not factor in all cash booked offshore. For example, Northrop Grumman reported in 2011 having $761 million offshore. But since 2012, the defense contractor has reported have that it continues to have permanently reinvested earnings, but no longer specifies how much.

Evidence Indicates Much of Offshore Profits are Booked to Tax Havens

Companies are not required to disclose publicly how much they earned—or booked on paper—in another country. Still, some companies provide enough information in their annual SEC filings to deduce that much of their offshore cash is sitting in tax havens.

Only 55 Fortune 500 companies disclose what they would pay in taxes if they did not keep their profits booked offshore.

Companies are required to disclose this information in their annual 10-K filings unless the company determines it is “not practicable” to do so—a major loophole.20 Collectively, these 55 companies alone would owe more than $147.5 billion in additional federal taxes. To put this enormous sum in context, it represents more than the entire state budgets of California, Virginia, and Indiana combined.21

More startling is that, as a group, the average tax rate these 55 companies have paid to foreign governments on these profits booked offshore seems to be a mere 6.7 percent.22 If these companies officially repatriated their “offshore” money to the U.S., they would pay the 35 percent statutory corporate tax rate, minus what they have already paid to foreign governments. This means that, for example, a corporation disclosing that it would pay a U.S. tax rate of 30 percent upon repatriation must have paid about 5 percent to foreign governments on its offshore profits. Based on such calculations, these 55 corporations seem to have paid a 6.7 percent rate to foreign governments, which suggests that the bulk of this cash is booked to tax havens that levy minimal to no corporate tax.

Examples of large companies paying very low foreign tax rates on offshore cash include:

- Apple: A recent Senate investigation found that Apple pays next to nothing in taxes on the profits it has booked offshore, which constitute the largest offshore cash stockpile. Manipulating tax loopholes in the U.S. and other countries, Apple structured two subsidiaries to be tax residents of neither the U.S.—where they are managed and controlled—nor Ireland—where they are incorporated. This arrangement ensures that they pay no taxes to any government on the lion’s share of their offshore profits. One of the subsidiaries has no employees.23

- American Express: The company officially reports $9.6 billion offshore for tax purposes, on which it would otherwise owe $3 billion in U.S. taxes. That implies it is currently paying a 3.8 percent tax rate on its offshore profits to foreign governments, suggesting that most of the money is booked in tax havens levying little to no tax.24 American Express maintains 23 subsidiaries in offshore tax havens.

- Nike: The sneaker giant officially holds $6.7 billion offshore for tax purposes, on which it would otherwise owe $2.2 billion in U.S. taxes. That implies Nike pays a mere 2.2 percent tax rate to foreign governments on those offshore profits, suggesting nearly all of the money is held by subsidiaries in tax havens. Nike does this in part by licensing the trademarks for some of its products to 12 subsidiaries in Bermuda. The American parent company must pay royalties to the Bermuda subsidiaries to use the trademarks in the U.S., thereby shifting its income offshore. Its Bermuda subsidiaries actually bear the names of their shoes like “Air Max Limited” and “Nike Flight.”25

New data shows that in 2010, more than half of the foreign profits reported by all multinationals for that year were booked to tax havens

In the aggregate, recently released data show that American multinationals collectively reported to the IRS 2010 earnings of $505 billion in 12 well known tax havens.

That is more than half (54%) of the total profits American companies reported earning abroad that year. For the five tax havens where American companies booked the most profits, those reported earnings were greater than the size of those country’s entire economies (as measured by GDP). This data indicates that there is little relationship between where American multinationals actually do business, and where they report that they made their profits for tax purposes.

Approximately 64 percent of the companies with tax haven subsidiaries registered at least one in Bermuda or the Cayman Islands—the two tax havens where profits from American multinationals accounted for the largest percentage of the two counties’ GDP.

|

Maximizing the benefit of offshore tax havens by reincorporating as a “foreign” company: a new wave of corporate “inversions” Some American companies go as far as to change the address of their corporate headquarters on paper so they can reincorporate in a foreign country, a maneuver called an ‘inversion,” which reflects how the scheme stands the reality of the corporate structure on its head. Inversion increases the reward for exploiting offshore loopholes. In theory, an American company must pay U.S. tax on profits it claims were made offshore if it wants to officially bring the money back to the U.S. to pay out dividends to shareholders or make certain U.S. investments. However, once a corporation reregisters as foreign, the profits it claims were earned for tax purposes outside the U.S. become fully exempt from U.S. tax. Even though a “foreign” corporation still must pay U.S. tax on profits it reports were earned in the U.S., corporate inversions are often followed by “earnings-stripping,” in which the corporation makes its remaining U.S. profits appear to be earned in other countries in order to avoid paying U.S. taxes on them. A corporation can do this by loading the American part of the company with debt owed to the foreign part of the company. The interest payments on the debt are tax deductible, officially reducing American profits, which are effectively shifted to the foreign part of the company.26 In 2004, Congress passed bipartisan legislation to crack down on inversions. The law now requires inverted companies that had at least 80 percent of the same shareholders as the pre-inversion parent to be treated as American companies for tax purposes, unless the company did “substantial business” in the country in which it was reincorporating.27 The Treasury’s definition of “substantial business” made this law difficult to game.28 However, in recent years, companies have discovered a way to circumvent the bipartisan anti-inversion laws by acquiring a smaller foreign company so that shareholders of the foreign company own more than 20 percent of the newly merged company.29 Walgreens and Pfizer—two quintessentially American companies—made headlines when it was revealed that they were considering mergers that would allow them to reincorporate abroad. A Bloomberg investigation found that 15 publicly traded companies have reincorporated abroad within the last few years, explaining that “most of their CEOs didn’t leave. Just the tax bills did.”30 |

Firms Reporting Fewer Tax Haven Subsidiaries Do Not Necessarily Dodge Fewer Taxes Offshore

In 2008, the Government Accountability Office conducted a study which revealed that 83 of the top 100 publically traded companies operated subsidiaries in offshore tax havens. Today, some companies report fewer subsidiaries in tax haven countries than they did in 2008. Meanwhile, some of these same companies reported significant increases in how much cash they hold abroad, and pay such a low tax rate to foreign governments that it suggests the money is booked to tax havens.

One explanation for this phenomenon is that companies are choosing not to report certain subsidiaries that they previously disclosed. The SEC requires that companies report all “significant” subsidiaries based on multiple measures of a subsidiary’s share of the company’s total assets. Furthermore, if the combined assets of all subsidiaries deemed “insignificant” collectively qualified as a significant subsidiary, then the company would have to disclose them. But a recent academic study found that the penalties for not disclosing subsidiaries are so light that a company might decide that disclosure isn’t worth the bad publicity. The researchers postulate that increased media attention on offshore tax dodging and/or IRS scrutiny could be a reason why some companies have stopped disclosing all subsidiaries. Examining the case of Google, the academics found that it was so improbable that the company could only have two significant foreign subsidiaries that Google “may have calculated that the SEC’s failure-to-disclose penalties are largely irrelevant and therefore may have determined that disclosure was not worth the potential costs associated with increases in either tax and/or negative publicity costs.”31 The researchers found that as of 2012, 23 no-longer-disclosed tax haven subsidiaries were still operating.

The other possibility is that companies are simply consolidating more income in fewer offshore subsidiaries, since having just one tax haven subsidiary is enough to dodge billions in taxes. For example, a 2013 Senate investigation of Apple found that the tech giant primarily uses two Irish subsidiaries—which own the rights to certain intellectual property—to hold on to $102 billion in offshore cash. Manipulating tax loopholes in the U.S. and other countries, Apple has structured these subsidiaries so that they are not tax residents of either the U.S. or Ireland, ensuring that they pay no taxes to any government on the lion’s share of the money. One of the subsidiaries has no employees. 32

Examples of large companies that have reported fewer tax haven subsidiaries in recent years while simultaneously shifting more profits offshore include:

- Citigroup reported operating 427 tax haven subsidiaries in 2008 but disclosed only 21 in 2013. Over that time period, Citigroup increased the amount of cash it reported holding offshore from $21.1 billion to $43.8 billion, ranking the company 10th for the amount of cash booked offshore. The company estimates it would owe $11.6 billion in taxes had it not booked those profits offshore. The company currently pays an 8.3 percent tax rate offshore, implying that most of those profits have been booked to low- or no-tax jurisdictions.

- Google reported operating 25 subsidiaries in tax havens in 2009, but since 2010 only discloses two, both in Ireland. During that period, it increased the amount of cash it had booked offshore from $7.7 billion to $38.9 billion. An academic analysis found that as of 2012, the 23 no-longer-disclosed tax haven subsidiaries were still operating.33 Google uses accounting techniques nicknamed the “double Irish” and the “Dutch sandwich,” according to a Bloomberg investigation. Using two Irish subsidiaries, one of which is headquartered in Bermuda, Google shifts profits through Ireland and the Netherlands to Bermuda, shrinking its tax bill by approximately $2 billion a year.34

- Microsoft reported operating 10 subsidiaries in tax havens in 2007; in 2013, it disclosed only five. During this same time period, the company increased the amount of money it held offshore from $6.1 billion to $76.4 billion, on which it would otherwise owe $19.4 billion in U.S. taxes. That implies that the company pays a tax rate of just 3 percent to foreign governments on those profits, suggesting that most of the cash is booked to tax havens. Microsoft ranks 4th for the amount of cash it reports offshore. A Wall Street Journal investigation found that over 90 percent of Microsoft “offshore” cash was actually invested by its offshore subsidiaries in U.S. assets like Treasuries, allowing for the company to benefit from the stability of the U.S. financial system without paying taxes on those profits.35

Measures to Stop Abuse of Offshore Tax Havens

Strong action to prevent corporations from using offshore tax havens will not only restore basic fairness to the tax system, but will alleviate pressure on America’s budget deficit and improve the functioning of markets. Markets work best when companies thrive based on their innovation or productivity, rather than the aggressiveness of their tax accounting schemes.

Policymakers should reform the corporate tax code to end the incentives that encourage companies to use tax havens, close the most egregious loopholes, and increase transparency so that companies can’t use layers of shell companies to shrink their tax burden.

End incentives to shift profits and jobs offshore.

- The most comprehensive solution to ending tax haven abuse would be to no longer permit U.S. multinational corporations to indefinitely defer paying U.S. taxes on the profits they attribute to their foreign subsidiaries. Instead, they should pay U.S. taxes on them immediately. “Double taxation” is not a danger because the companies already subtract any foreign taxes they’ve paid from their U.S. tax bill, and that would not change. Ending deferral would raise nearly $600 billion in tax revenue over ten years, according to the Joint Committee on Taxation analysis of 2012 legislation.36

- Reject a “territorial” tax system. Tax haven abuse would be worse under a system in which companies could temporarily shift profits to tax haven countries, pay minimal or no tax under those countries’ tax laws, and then freely use the profits in the United States without paying any U.S. taxes. The Treasury Department estimates that switching to a territorial tax system could add $130 billion to the deficit over ten years.37

Close the most egregious offshore loopholes.

Policy makers can take some basic common-sense steps to curtail some of the most obvious and brazen ways that some companies abuse offshore tax havens.

- Stop companies from licensing intellectual property (e.g. patents, trademarks, licenses) to shell companies in tax haven countries and then paying inflated fees to use them. This common practice allows companies to legally book profits that were earned in the U.S. to the tax haven subsidiary owning the patent. Proposals made by President Obama could save taxpayers $23.2 billion over ten years, according to the Joint Committee on Taxation.38

- Treat the profits of publicly traded “foreign” corporations that are managed and controlled in the United States as domestic corporations for income tax purposes.

- Reform the so-called “check-the-box” rules to stop multinational companies from manipulating how they define their corporate status to minimize their taxes. Right now, companies can make inconsistent claims to maximize their tax advantage, telling one country they are one type of corporate entity while telling another country the same entity is something else entirely.

- Close the current loophole that allows U.S. companies that shift income to foreign subsidiaries to place that money in foreign branches of American financial institutions without it being considered repatriated, and thus taxable. This “foreign” U.S. income should be taxed when the money is deposited in U.S. financial institutions.

- Stop companies from taking bigger tax credits than the law intends for the taxes they pay to foreign countries by reforming foreign tax credits. Proposals to “pool” foreign tax credits would save $58.6 billion over ten years, according to the Joint Committee on Taxation.39

- Stop companies from deducting interest expenses paid to their own offshore affiliates, which put off paying taxes on that income. Right now, an offshore subsidiary of a U.S. company can defer paying taxes on interest income it collects from the U.S.-based parent, even while the U.S. parent claims those interest payments as a tax deduction. This reform would save 51.4 billion over ten years, according to the Joint Committee on Taxation.40

Increase transparency.

- Require full and honest reporting to expose tax haven abuse. Multinational corporations should report their profits on a country-by-country basis so they can’t mislead each nation about the share of their income that was taxed in the other countries. An annual survey of CEOs around the globe done by PricewaterhouseCoopers found that nearly 60 percent of the CEOs support this reform.41

Methodology

To calculate the number of tax haven subsidiaries maintained by the Fortune 500 corporations, we used the same methodology as a 2008 study by the Government Accountability Office that used 2007 data (see endnote 4).

The list of 50 tax havens used is based on lists compiled by three sources using similar characteristics to define tax havens. These sources were the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), the National Bureau of Economic Research, and a U.S. District Court order. This court order gave the IRS the authority to issue a “John Doe” summons, which included a list of tax havens and financial privacy jurisdictions.

The companies surveyed make up the 2013 Fortune 500, a list of which can be found here: http://money.cnn.com/magazines/fortune/fortune500/.

To figure out how many subsidiaries each company had in the 50 known tax havens, we looked at “Exhibit 21” of each company’s 2013 10-K report, which is filed annually with the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC). Exhibit 21 lists out every reported subsidiary of the company and the country in which it is registered. We used the SEC’s EDGAR database to find the 10-K filings.

We also used 10-K reports to find the amount of money each company reported it kept offshore in 2013. This information is typically found in the tax footnote of the 10-K. The companies disclose this information as the amount they keep “permanently reinvested” abroad.

As explained in this report, 55 of the companies surveyed disclosed what their estimated tax bill would be if they repatriated the money they kept offshore. This information is also found in the tax footnote. To calculate the tax rate these companies paid abroad in 2013, we first divided the estimated tax bill by the total amount kept offshore. That number multiplied by 100 equals the U.S. tax rate the company would pay if they repatriated that foreign cash. Since companies receive dollar-for-dollar credits for taxes paid to foreign governments, the tax rate paid abroad is simply the difference between 35%—the U.S. statutory corporate tax rate—and the tax rate paid upon repatriation.

End Notes

1 Government Accountability Office, Business and Tax Advantages Attract U.S. Persons and Enforcement Challenges Exist, GAO-08-778, a report to the Chairman and Ranking Member, Committee on Finance, U.S. Senate, July 2008, http://www.gao.gov/highlights/d08778high.pdf.

2 Id.

3 Jane G. Gravelle, Congressional Research Service, Tax Havens: International Tax Avoidance and Evasion, 4 June 2010.

4 Government Accountability Office, International Taxation; Large U.S. Corporations and Federal Contractors with Subsidiaries in Jurisdictions Listed as Tax Havens or Financial Privacy Jurisdictions, December 2008.

5 Mark P. Keightley, Congressional Research Service, An Analysis of Where American Companies Report Profits: Indications of Profit Shifting, 18 January, 2013.

6 Citizens for Tax Justice, American Corporations Report Over Half of Their Offshore Profits as Earned in 12 Tax Havens, 28 May 2014.

7 Offshore Funds Located On Shore, Majority Staff Report Addendum, Senate Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations, 14 December 2011, http://www.levin.senate.gov/newsroom/press/release/new-data-show-corporate-offshore-funds-not-trapped-abroad-nearly-half-of-so-called-offshore-funds-already-in-the-united-states/.

8 Kate Linebaugh, “Firms Keep Stockpiles of ‘Foreign’ Cash in U.S.,” Wall Street Journal, 22 January 2013, http://online.wsj.com/article/SB10001424127887323284104578255663224471212.html.

9 Kitty Richards and John Craig, Offshore Corporate Profits: The Only Thing ‘Trapped’ Is Tax Revenue, Center for American Progress, 9 January, 2014, http://www.americanprogress.org/issues/tax-reform/report/2014/01/09/81681/offshore-corporate-profits-the-only-thing-trapped-is-tax-revenue/.

10 Kimberly A. Clausing, “The Revenue Effects of Multinational Firm Income Shifting,” Tax Notes, 28 March 2011, 1560-1566.

11 Phineas Baxandall, Dan Smith, Tom Van Heeke, and Benjamin Davis. Picking up the Tab, U.S. PIRG, April 2014. http://uspirg.org/reports/usp/picking-tab-2014.

12 “China to Become World’s Second Largest Consumer Market”, Proactive Investors United Kingdom, 19 January, 2011 (Discussing a report released by Boston Consulting Group), http://www.proactiveinvestors.co.uk/columns/china-weekly-bulletin/4321/china-to-become-worlds-second-largest-consumer-market-4321.html.

13 The number of subsidiaries registered in tax havens is calculated by authors looking at exhibit 21 of the company’s 2013 10-K report filed annually with the Securities and Exchange Commission. The list of tax havens comes from the Government Accountability Office report cited in note 5.

14 The amount of money that a company has booked offshore and the taxes the company would owe if they repatriated that income can also be found in the 10-K report; however, not all companies disclose the latter information.

15 See note 12.

16 Calculated by the authors based on revenue information from Pfizer’s 2012 10-K filing.

17 Audit Analytics, “Overseas Earnings of Russell 1000 Tops $2 Trillion in 2013,” 1 April 2014. http://www.auditanalytics.com/blog/overseas-earnings-of-russell-1000-tops-2-trillion-in-2013/.

18 See note 6.

19 Kimberly A. Clausing, “Multinational Firm Tax Avoidance and Tax policy,” 62 Nat’l Tax J 703, December 2009; see note 10 for more recent study.

20 Citizens for Tax Justice, “Apple is not Alone” 2 June 2013, http://ctj.org/ctjreports/2013/06/apple_is_not_alone.php#.UeXKWm3FmH8.

21 Budget information comes from a database compiled by the National Association of State Budget Officers. California’s current budget is $97 billion http://www.ebudget.ca.gov/2013-14/pdf/Enacted/BudgetSummary/FullBudgetSummary.pdf; Virginia’s current budget is $42 billion – https://solutions.virginia.gov/pbreports/rdPage.aspx?rdReport=BDOC2014_FrontPage, Indiana’s current budget is $6.7 billion – http://www.in.gov/sba/files/AP_2013_0_0_2_Budget_Report.pdf. The three together add up to $145.7 billion.

22 See methodology for an explanation of how this was calculated.

23 Offshore Profit Shifting and the U.S. Tax Code—Part 2,Senate Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations, 21 May, 2013, http://www.hsgac.senate.gov/subcommittees/investigations/hearings/offshore-profit-shifting-and-the-us-tax-code_-part-2.

24 Companies get a credit for taxes paid to foreign governments when they repatriate foreign earnings. Therefore, if companies disclose what their hypothetical tax bill would be if they repatriated “permanently reinvested” earnings, it is possible to deduce what they are currently paying to foreign governments. For example, if a company discloses that they would need to pay the full statutory 35% tax rate on its offshore cash, it implies that they are currently paying no taxes to foreign governments, which would entitle them to a tax credit that would reduce the 35% rate. This method of calculating foreign tax rates was original used by Citizens for Tax Justice (see note 21).

25 Citizens for Tax Justice, “Nike’s Tax Haven Subsidiaries Are Named After Its Shoe Brands,” 25 July 2013, http://www.ctj.org/taxjusticedigest/archive/2013/07/nikes_tax_haven_subsidiaries_a.php#.U3y0Gijze2J.

26 Citizens for Tax Justice, “The Problem of Corporate Inversions: the Right and Wrong Approaches for Congress,” 14 May 2014, http://ctj.org/ctjreports/2014/05/the_problem_of_corporate_inversions_the_right_and_wrong_approaches_for_congress.php#.U3tavSjze2J.

27 Other consequences kick in for inversions involving 60‐79.9% of the same shareholders. This law is based on a 2002 bill introduced by Senator Charles Grassley (R-IA) and former Sen. Max Baucus (D-MT). See 26 U.S.C.§7874 (available at http://codes.lp.findlaw.com/uscode/26/F/80/C/7874/).

28 Treasury first defined “substantial business” in 2006 with a relatively loose bright line standard. That 2006 standard was replaced in 2009 with a vague facts and circumstances test and an intent to make inverting harder.Companies got comfortable with that approach too, however, and resumed inverting. On June 7, 2012, Treasury issued new temporary rules creating a difficult-to-evade bright line test. Specifically, the new rules define substantial business as a minimum of 25 percent of an inverting company’s business. That is a hard threshold to meet if the main “business” in country is a post office box. But the rules go further by making the standard hard to game; the 25 percent has to be met in three different ways. Moreover, those measurements must be taken a year before the inversion, so the inversion process itself cannot be manipulated to meet the thresholds. For a more detailed discussion of the history of the interpretations, see Latham & Watkins Client Alert No. 1349, “IRS Tightens Rules on Corporate Expatriations—New Regulations Require High Threshold of Foreign Business Activity” June 12, 2012, http://www.google.com/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=14&ved=0CFsQFjADOAo&url=http%3A%2F%2Fwww.lw.com%2FthoughtLeadership%2FIRSTightensRulesonCorporateExpatriations&ei=fPYmUIeDca36gG5q4GICg&usg=AFQjCNEMzRNjJYwoJtmyd4VJFDnap_hxA.

29 Citizens for Tax Justice, “The Problem of Corporate Inversions: the Right and Wrong Approaches for Congress,” 14 May 2014. http://ctj.org/ctjreports/2014/05/the_problem_of_corporate_inversions_the_right_and_wrong_approaches_for_congress.php#.U3tavSjze2J.

30 Zachary R. Mider, “Tax Break ‘Blarney’: U.S. Companies Beat the System with Irish Addresses,” Bloomberg News, 5 May 2014, http://www.bloomberg.com/news/2014-05-04/u-s-firms-with-irish-addresses-criticized-for-the-moves.html.

31 Jeffrey Gramlich and Janie Whiteaker-Poe, “Disappearing subsidiaries: The Cases of Google and Oracle,” March 2013, Working Paper available at SSRN, http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2229576.

32 See note 25.

33 See note 27.

34 Jesse Drucker, “Google Joins Apple Avoiding Taxes with Stateless Income,” Bloomberg News, 22 May 2013, http://www.bloomberg.com/news/2013-05-22/google-joins-apple-avoiding-taxes-with-stateless-income.html.

35 See note 14.

36 “Fact Sheet on the Sanders/Schakowsky Corporate Tax Fairness Act,” February 7, 2012, http://www.sanders.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/CORPTA%20FAIRNESSFACTSHEET.pdf.

37 The President’s Economic Recovery Board, The Report on Tax Reform Options: Simplification, Compliance, and Corporate Taxation, August 2010, http://www.treasury.gov/resource-center/tax-policy/Documents/PERAB-Tax-Reform-Report-8-2010.pdf.

38 Joint Committee on Taxation, “Estimated Budget Effects of the Revenue Provisions Contained in the President’s Fiscal Year 2015 Budget Proposal,” April 15, 2015, https://www.jct.gov/publications.html?func=startdown&id=4585.

39 Id.

40 Id.

41 Cited in Tom Bergin, “CEOs back country-by-country tax reporting—survey,” Reuters, 23 April 2014. http://uk.reuters.com/article/2014/04/23/uk-taxcompanies-idUKBREA3M18I20140423.