March 12, 2014 12:00 AM | Permalink | ![]()

The President’s proposed budget for next year includes two broad categories of tax proposals. First are the provisions that mostly benefit individuals and provisions that raise revenue, which are described in this report. Second are the provisions presented by the administration as part of a business tax reform that the President, unfortunately, proposes to enact in a way that is revenue-neutral. The latter proposals are discussed in a separate CTJ report[1]

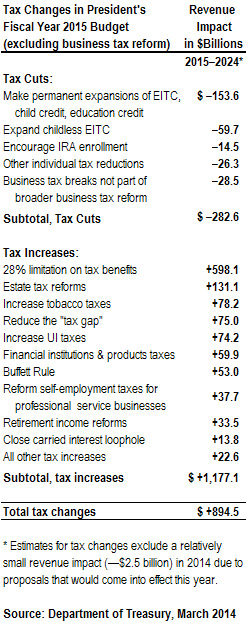

The President’s tax cut proposals are relatively well-targeted to support work and education, and his revenue-raising proposals would finance public investments in a generally progressive way. The table on the right lists these proposals and their projected revenue impacts. As the table illustrates, this part of the President’s budget would provide $282.6 billion in tax cuts over a decade, mostly for low- and middle-income families, and would raise revenue by almost $1.2 trillion over that same period. The net effect would be to raise $894.5 billion over a decade.

The proposals include making permanent the previously enacted expansions of the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) and other refundable tax credits and expanding the EITC for childless workers, who currently are the only demographic that is subject to federal income tax even if they fall below the official poverty line.

In order to offset the costs of the expanded EITC for childless workers, the President proposes to close the “John Edwards/Newt Gingrich Loophole” for Subchapter S corporations and also close the “carried interest” loophole that allows buyout-fund managers like Mitt Romney to pay a lower effective tax rate than many middle-income people. In order to offset the costs of a proposed expansion in preschool education, the President proposes a large increase in the federal tobacco tax.

The proposals include some very progressive revenue-raising measures — most notably raising nearly $600 billion over a decade by limiting the benefits of certain income tax deductions and exclusions for high-income people.

Tax Cut Proposals

Make Permanent Recent Expansions of the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC), Child Tax Credit (CTC), and American Opportunity Tax Credit (AOTC)

Ten-Year Revenue Impact: —$153.6 billion

The American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 (ARRA) temporarily expanded three refundable income tax credits. These provisions have since been extended twice, most recently as part of the January 2013 “fiscal cliff” deal. While that legislation made permanent most of the Bush-era tax cuts, including many that disproportionately benefit high-income people, the expansions of refundable tax credits for working people were extended only through 2017.

The EITC, CTC and AOTC are refundable income tax credits, meaning they can benefit taxpayers who are too poor to have any federal income tax liability. A tax credit that is not refundable cannot lower one’s income tax liability to less than zero, but a refundable tax credit can result in negative income tax liability, meaning the taxpayer receives a check from the IRS.

The EITC is completely refundable while the CTC is partially refundable. The EITC is a credit equal to a certain percentage of earnings (40 percent of earnings for a family with two children, for example) up to a maximum amount (yielding a maximum credit of $5,460 for a family with two children in 2014). It is phased out at higher income levels. The CTC is a credit equal to a maximum of $1,000 per child. The refundable part of the CTC is equal to 15 percent of earnings above $3,000 (up to the $1,000 per child maximum). The CTC is also phased out at higher income levels.

The EITC was first enacted in 1975 and has been expanded several times since then. President Ronald Reagan praised the part of the Tax Reform Act of 1986 that expanded the EITC, calling it “the best antipoverty, the best pro-family, the best job creation measure to come out of Congress.”

Several empirical studies have found that the EITC increases hours worked by the poor. These studies have also found that the EITC has had a particularly strong effect in increasing the hours worked by low-income single parents, and there is evidence that it had a larger impact on hours worked than did the work requirements and benefit limits enacted as part of welfare reform.[2]

The refundable part of the CTC is likely to have similar impacts. The EITC and the refundable part of the CTC are credits equal to a certain percentage of earnings, meaning these refundable tax credits are only available to those who work.

The 2009 expansion of the EITC set a higher credit rate for families with three or more children and increased the income level above which the credit begins to phase out for married couples. The expansion of the CTC reduced the minimum level of earnings required to receive a refundable credit.

In 2012, when it appeared that conservative members of Congress wanted to allow the expansions of the EITC and CTC to expire, Citizens for Tax Justice estimated that tax benefits for 13 million families with 26 million children were at stake.[3] Fortunately, these provisions (along with the AOTC) were extended, but it is unclear whether Congress will extend them again after 2017.

The AOTC is an expansion of the HOPE credit for higher education that was first enacted in 2009. The AOTC allows a credit of 100 percent of the first $2,000 spent on higher education and 25 percent of the next $2,000; the maximum credit is $2,500. The provision allows the credit for the first four years of post-secondary education (compared to only the first two years under prior law). The provision also allows the credit to be used for amounts paid for course materials (in addition to tuition and fees) and makes 40 percent of the credit refundable. The President’s Budget would make the AOTC provisions permanent.

Expand EITC for Childless Workers

Ten-Year Revenue Impact: —$59.7 billion

The EITC available to childless workers is currently very small, with a maximum credit of only $503 in 2015. The President proposes to increase the credit rate for childless workers from 7.65 percent to 15.3 percent, which would double the maximum credit. The proposal would also increase the income level at which the childless credit begins to phase out, from $8,220 to $11,500. As a result, the income level at which the credit for childless workers is fully phased out would increase from $14,790 under the current rules to $18,070 under the President’s proposal.

The proposal would also lower the minimum age of eligibility for the childless credit from 25 to 21, so that the credit no longer excludes young people struggling at the start of their working lives.[4] The proposal would also raise the maximum age of eligibility from 64 to 66 to address the fact that people no longer can receive full Social Security retirement benefits at age 65, as was the case when the existing EITC rules were first enacted.

Encourage Individual Retirement Account Enrollment

Ten-Year Revenue Impact: —$14.5 billion

The President proposes to require most employers who do not offer retirement savings plans to automatically divert three percent of an employee’s wages or salary into an Individual Retirement Acount (IRA), unless the employee opts out of the arrangement or opts to make contributions at a different rate. Contributions would not be required from the employer.

IRAs are tax-advantaged retirement savings vehicles. Individuals are allowed to contribute up to $5,500 of income per year (this limit is adjusted annually) to such accounts and defer paying income tax on either the contributions or the earnings until the money is paid out during retirement. IRAs were originally created to provide an incentive for people to save for retirement even if they have no employer-sponsored retirement plan like a 401(k) or a traditional pension. However, there is little evidence that IRAs or any of the existing retirement tax provisions actually result in savings among people who would not have saved anyway even in the absence of any such tax break.

Some research suggests that policies creating a default rule of saving for retirement, as the President’s proposal would do, would be more effective than existing policies in encouraging people to save.[5] Whether this is a good idea for low-income workers is questionable, or at least debatable.

To defray the costs to employers of setting up the default payments into IRAs, the President’s proposal would also provide non-refundable tax credits to affected employers equal to $500 during the first year, $250 in the second year, and $25 per enrolled employee up to a total of $250 for the next six years. Non-refundable credits of $1,000 would be provided for employers that establish other retirement savings plans.

Revenue-Raising Proposals

Limit Tax Savings of Certain Deductions and Exclusions to 28 Percent

Ten-Year Revenue Impact: +$598.1 billion

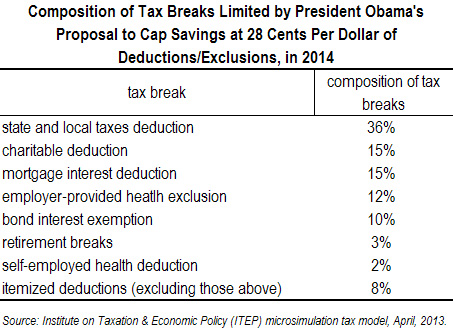

This proposal, often called a “28 percent limitation,” would limit the tax savings for high-income taxpayers from itemized deductions and certain other deductions and exclusions to 28 cents for each dollar deducted or excluded. Last year CTJ estimated that if this reform was in effect in 2014, it would result in a tax increase for only 3.6 percent of Americans, and their average tax increase would equal less than one percent of their income — despite raising an enormous amount of revenue.[6]

The President’s proposal is a way of limiting tax expenditures for the wealthy. The term “tax expenditures” refers to provisions that are government subsidies provided through the tax code. As such, tax expenditures have the same effect as direct spending subsidies, because the Treasury ends up with less revenue and some individual or group receives money. But tax subsidies are sometimes not recognized as spending programs because they are implemented through the tax code.

Tax expenditures that take the form of deductions and exclusions are used to subsidize all sorts of activities. For example, deductions allowed for charitable contributions and mortgage interest payments subsidize philanthropy and home ownership. Exclusions for interest from state and local bonds subsidize lending to state and local governments.

Under current law, there are three income tax brackets with rates higher than 28 percent (the 33, 35, and 39.6 percent brackets). People in these tax brackets (and people who would be in these tax brackets if not for their deductions and exclusions) could therefore lose some tax breaks under the proposal.

Currently, a high-income person in the 39.6 percent income tax bracket saves almost 40 cents for each dollar of deductions or exclusions. An individual in the 35 percent income tax bracket saves 35 cents for each dollar of deductions or exclusions, and a person in the 33 percent bracket saves 33 cents. The lower tax rates are 28 percent or less. Many middle-income people are in the 15 percent tax bracket and therefore save only 15 cents for each dollar of deductions or exclusions.

This is an odd way to subsidize activities that Congress favors. If Congress provided such subsidies through direct spending, there would likely be a public outcry over the fact that rich people are subsidized at higher rates than low- and middle-income people. But because these subsidies are provided through the tax code, this fact has largely escaped the public’s attention.

President Obama initially presented his proposal to limit certain tax expenditures in his first budget plan in 2009, and included it in subsequent budget and deficit-reduction plans each year after that. The original proposal applied only to itemized deductions. The President later expanded the proposal to limit the value of certain “above-the-line” deductions (which can be claimed by taxpayers who do not itemize), such as the deduction for health insurance for the self-employed and the deduction for contributions to individual retirement accounts (IRA).

More recently, the proposal was also expanded to include certain tax exclusions, such as the exclusion for interest on state and local bonds and the exclusion for employer-provided health care. Exclusions provide the same sort of benefit as deductions, the only difference being that they are not counted as part of a taxpayer’s income in the first place (and therefore do not need to be deducted).

Estate Tax Reforms

Ten-Year Revenue Impact: +$131.1 billion

The most significant proposal in this category would increase estate and gift taxes by returning to the estate tax and gift tax rules in place in 2009. Back then, only 0.3 percent of deaths resulted in estate tax liability.[7] Today even fewer estates are subject to the estate tax. Returning to the 2009 rules would increase revenue by $118.3 billion over a decade.

The federal estate tax has had a complicated recent history. The tax cuts enacted under President George W. Bush gradually shrank the estate tax by increasing over time the amount of estate value that is exempt from the tax and lowering the estate tax rate, and then repealed the estate tax entirely in 2010. The estate tax was supposed to return to its pre-Bush levels after the Bush-era tax cuts expired, but the deal struck by President Obama and Congress to extend most of the expiring tax cuts allowed the estate tax to return only as a shell of its former self.

The estate tax exempts a certain (large) amount of the value of any estate from taxation and provides a deduction for charitable bequests that further reduces the amount of the estate that is actually taxable. Bequests to spouses are exempt from the tax.

This year, the federal estate tax has a basic exemption of $5,340,000 (effectively double that for couples). On the taxable estate, the tax rate is 40 percent. Most estates that are taxable have an effective tax rate much lower than 40 percent because of exemptions and deductions.

The rules in place in 2009, to which President Obama proposes to return, include a basic exemption of $3,500,000 per spouse and a rate of 45 percent.

The President also proposes some additional reforms to close loopholes in the estate tax. One seemingly arcane proposal along these lines is to “require a minimum term for GRATs.”

A person owning an asset with a quickly rising value may want to find some way to “lock in” its current value for purposes of calculating estate and gift taxes before it rises any further. One way is to place the asset in a certain type of trust (a Grantor Retained Annuity Trust, or GRAT) that pays an annuity for a certain time and then leaves whatever assets remain to the trust’s beneficiaries.

The gift to the trust’s beneficiaries is valued when the trust is set up, rather than when it’s received by the beneficiaries. This benefit is particularly difficult to justify when the trust has a very short term (perhaps just a couple years) and wealthy people have used such short-term trusts to aggressively reduce or even eliminate any tax on gifts to their children. The President’s proposal would require a GRAT to have a minimum term of 10 years, increasing the chance that the grantor will die during the GRAT’s term and the assets will be included in the grantor’s estate and thus subject to the estate tax.

Increase Tobacco Taxes

Ten-Year Revenue Impact: +$78.2 billion

The President proposes to increase the federal tobacco taxes from the current rate of $1.01 per pack of cigarettes to $1.95 per pack, and to use the resulting revenue to fund preschool education.

The current federal tobacco tax rate was set in 2009 to fund health insurance for children. States also impose tobacco taxes, which range from 17 cents per pack in Missouri to $4.35 per pack in New York.

Given the well-documented and widely recognized harm that cigarette smoking causes to health, a tax on tobacco is a reasonable way to improve health if it discourages smoking, particularly among young people who may be discouraged from taking up the habit if the cost is too high.

But if the purpose of tobacco taxes is to fund important programs, making the government partly dependent on them as a source of revenue, the merits of this approach are more ambiguous because tobacco taxes are regressive, meaning they take a much larger share of income from low-income families than they take from high-income families.

This regressivity is further exacerbated by the fact that low-income individuals are more likely to smoke than their upper-income neighbors. In 2009 the poorest twenty percent of non- elderly Americans spent 0.9 percent of their income, on average, on these taxes, while the wealthiest 1 percent spent less than 0.1 percent of their income on cigarette taxes. In other words, cigarette taxes are about ten times more burdensome for low-income taxpayers than for the wealthy.[8]

Some recent research challenges the argument that tobacco taxes are regressive by pointing out that the benefits of the tax are themselves quite progressive, because low-income people are more likely than anyone else to stop smoking in response to the tax. As a recent report explains,

“Because low-income people are more sensitive to changes in tobacco prices, they will be more likely than high-income people to smoke less, quit, or never start in response to a tax increase. This means that the health benefits of the tax increase would be progressive. One forthcoming study concludes that people below the poverty line paid 11.9 percent of the tobacco tax increase enacted in 2009 but will receive 46.3 percent of the resulting health benefits, as measured by reduced deaths.”[9]

Reduce the “Tax Gap” by Improving Compliance

Ten-Year Revenue Impact: +$75.0 billion

The “tax gap” is the difference between the federal taxes that people and businesses owe and the federal taxes they actually paid in a given year. The IRS recently estimated that in 2006 the federal tax gap was $385 billion.[10] This somewhat wild guess at the annual revenue loss indicates that efforts to narrow the tax gap, even if only partially successful, could generate significant revenue.

The largest of the President’s proposals in this category would raise $52 billion over a decade by providing additional funds to the IRS for enforcement and compliance measures. Such funding was significantly reduced by the Budget Control Act of 2011, despite the fact that the cuts actually added to the federal budget deficit.

As Nina Olsen, the United States Taxpayer Advocate, notes in her most recent annual report, cutting the IRS budget makes little sense since every “dollar spent on the IRS generates more than one dollar in return — it reduces the budget deficit.”

Since 2010, the IRS budget has been cut 8 percent (adjusted for inflation), forcing the IRS to reduce its staff by 11,000 people and its spending on training its employees by 83 percent. These cuts have taken place even though there are now 11 percent more individual tax returns and 23 percent more business returns for the agency to handle. A recent report by the Treasury Inspector General for Tax Administration (TIGTA) found that at least $8 billion had been lost in compliance revenue due to budget cuts.[11]

The administration’s proposal would increase funding for IRS enforcement and compliance activities by $480 million in 2015 and provide further increases in years beyond that. The administration predicts that this spending would more than pay for itself, increasing revenue by $52 billion over the upcoming decade.

Increase Unemployment Insurance Taxes

Ten-Year Revenue Impact: +$74.2 billion

The main proposal in this category would increase the Federal Unemployment Insurance Act (FUTA) tax that employers pay to fund the federal unemployment insurance fund, while also providing short-term relief to employers in states where FUTA taxes recently went up because the states had exhausted their UI trust funds.

Under current law, employers pay FUTA taxes on the first $7,000 of wages of an employee, usually at a very low rate, to fund the administration of UI programs in each state. Employers also pay state UI payroll taxes to finance state UI trust funds, which are supposed to be the main source of UI benefits. But when state trust funds are exhausted — which has been common in recent years — states must borrow from the federal UI trust fund. The principal is repaid by increases in the FUTA tax that employers must pay in the state that has taken on this debt. The interest must be repaid by the state, and states often levy an additional tax on employers for this purpose.

The proposal would suspend interest payments on this debt and suspend the FUTA increases for employers in the indebted states in 2014 and 2015. But in the long run the proposal would raise revenue because it would also increase the “wage base,” the amount of wages that FUTA taxes apply to, from the first $7,000 earned to the first $15,000 earned per employee, which would result in a higher revenue yield even though the proposal also lowers the FUTA rate.

Reform Treatment of Financial Institutions and Products

Ten-Year Revenue Impact: +$59.9 billion

The main proposal in this category is a tax of 0.17 percent of the value of the riskier assets held by the nation’s 50 largest financial institutions (those with assets of more than $50 billion each). The fee would raise $56.0 billion over the next decade. The purpose of the fee would be to recover taxpayer money used by the Bush administration to bail out financial institutions and to reduce the excessive risk-taking that necessitated the bailout.

Excessive risk-taking by the financial industry as a whole led to a systemic meltdown at the end of the Bush administration. As a result, the banking system as a whole began to fail, meaning businesses were unable to obtain credit, making it impossible for them to function. The bailout propped up the banking system to avoid a deeper recession, but the distasteful side effect is that the largest banks know full well that they are now considered “too big to fail.”

So now the biggest banks have insufficient incentive to avoid the sort of risk-taking that led to the collapse. The implicit government guarantee gives them a special advantage that smaller banks don’t have, since banks that are not considered “too big to fail” are less likely to be bailed out by the federal government. The proposed fee would seem to address these problems at least to some extent, by reducing the incentive for risk-taking as well as the advantage that the largest banks have over smaller banks.

Progressive supporters of the proposed bank fee have been joined by some noted conservatives. Greg Mankiw, Chairman of President George W. Bush’s Council of Economic Advisers, and David Stockman, director of the Office and Management and Budget under President Reagan, both support the proposed bank fee.[12]

Fair Share Tax to Implement the “Buffett” Rule”

Ten-Year Revenue Impact: +$53.0 billion

The “Buffett Rule” began as a principle, proposed by President Obama, that the tax system should be reformed to reduce or eliminate situations in which millionaires pay lower effective tax rates than many middle-income people. This principle was inspired by billionaire investor Warren Buffett, who declared publicly that it was a travesty that he was taxed at a lower effective rate than his secretary.

At the time, Citizens for Tax Justice argued that the most straightforward way to implement this principle would be to eliminate the special low personal income tax rate for capital gains and stock dividends (the main reason why wealthy investors like Mitt Romney and Warren Buffett can pay low effective tax rates) and tax all income at the same rates.[13]

The President’s Fair Share Tax implements the Buffett Rule in a more round-about way by applying a minimum tax of 30 percent to the income of millionaires. This would raise much less revenue than simply ending the break for capital gains and dividends, for several reasons.

First, taxing capital gains and dividends as ordinary income would subject them to a top rate of 39.6 percent while the Fair Share Tax (a minimum tax) would have a rate of just 30 percent. Second, the proposed minimum income tax rate on capital gains and dividend income would effectively be less than 30 percent because it would take into account the 3.8 percent Medicare tax on investment income that was enacted as part of health care reform. Third, even though most capital gains and dividend income goes to the richest one percent of taxpayers, there is still a great deal that goes to taxpayers who are among the richest five percent or even one percent but are not millionaires and therefore not subject to the Fair Share Tax.

Other reasons for the lower revenue impact of the President’s proposal (compared to repealing the preference for capital gains and dividends) have to do with how it is designed. For example, the minimum tax would be phased in for people with incomes between $1 million and $2 million. Otherwise, a person with adjusted gross income of $999,999 who has effective tax rate of 15 percent could make $2 more and see his effective tax rate shoot up to 30 percent. Tax rules are generally designed to avoid this kind of unreasonable result.

The legislation also accommodates those millionaires who give to charity by applying the minimum tax of 30 percent to adjusted gross income less charitable deductions.

Reform Self-Employment Taxes for Professional Services (Close the John Edwards/Newt Gingrich Loophole for S Corporations)

Ten-Year Revenue Impact: +$37.7 billion

To partly offset the cost of his EITC expansion, the President proposes to close a payroll tax loophole that allows many self-employed people, infamously including two former lawmakers, John Edwards and Newt Gingrich, to use “S corporations” to avoid payroll taxes. Payroll taxes are supposed to be paid on income from work. The Social Security payroll tax is paid on the first $117,000 in earnings (adjusted each year) and the Medicare payroll tax is paid on all earnings. These rules are supposed to apply both to wage-earners and self-employed people.

“S corporations” are essentially partnerships, except that they enjoy limited liability, like regular corporations. The owners of both types of businesses are subject to income tax on their share of the profits, and there is no corporate level tax. But the tax laws treat owners of S corporations quite differently from partners when it comes to Social Security and Medicare taxes. Partners are subject to these taxes on all of their “active” income, while active S corporation owners pay these taxes only on the part of their “active” income that they report as wages. In effect, S corporation owners are allowed to determine what salary they would pay themselves if they treated themselves as employees.

Naturally, many S corporation owners likely make up a salary for themselves that is much less than their true work income in order to avoid Social Security payroll taxes and especially Medicare payroll taxes.[14]

Under the President’s proposal, businesses providing professional services would be taxed the same way for payroll tax purposes regardless of whether they are structured as S corporations or partnerships.

Retirement Income Reforms

Ten-Year Revenue Impact: +$33.5 billion

The most significant proposal in this category would “limit the total accrual of tax-favored retirement benefits” and raise $28.4 billion over a decade. In other words, the amount of money an individual can save in a retirement account that is tax-advantaged would be sensibly limited, so that the tax code is not being used to subsidize enormous amounts of retirement savings for extremely wealthy individuals.

In 2013, Citizens for Tax Justice proposed that Congress enact a proposal of this type in response to news reports that Mitt Romney had $87 million saved in an individual retirement account (IRA), which allows individuals to defer paying taxes on the income saved until retirement.[15] The Obama administration first proposed this change in the budget plan it released later that same year.

Under current law, there are limits on how much an individual can contribute to tax-advantaged retirement savings vehicles like 401(k) plans or IRAs, but there is actually no limit on how much can be accumulated in such savings vehicles.

The contribution limit for IRAs is $5,500, adjusted each year, plus an additional $1,000 for people over age 50. It probably never occurred to many lawmakers that a buyout fund manager like Mitt Romney would somehow engineer a method to end up with tens of millions of dollars in his IRA.

The President proposes to essentially align the rules of 401(k)s and IRAs with the rules for “defined benefit” plans (traditional pensions). Under current law, in return for receiving tax advantages, defined benefit plans are subject to certain limits including a $210,000 annual limit on benefits paid out in retirement (adjusted each year). The President’s proposal would, very generally, limit the contributions and accruals in all the 401(k) plans and IRAs owned by an individual to whatever amount is necessary to pay out at that limit when the individual reaches retirement.

Restrict Carried Interest Loophole

Ten-Year Revenue Impact: +$13.8 billion

If Congress does not eliminate the tax preference for capital gains (as explained earlier) then it should at least eliminate the loopholes that allow the tax preference for income that is not truly capital gains. The most notorious of these loopholes is the one that allows “carried interest” to be taxed as capital gains. The President proposes to close the carried interest loophole to partly offset the cost of his EITC expansion.

Some businesses, primarily private equity, real estate and venture capital, use a technique called a “carried interest” to compensate their managers. Instead of receiving wages, the managers get a share of the profits from investments that they manage, without having to invest their own money. The tax effect of this arrangement is that the managers pay taxes on their compensation at the special, low rates for capital gains (up to 20 percent) instead of the ordinary income tax rates that normally apply to wages and other compensation (up to 39.6 percent). This arrangement also allows them to avoid payroll taxes, which apply to wages and salaries but not to capital gains.

Income in the form of carried interest can run into the hundreds of millions (or even in excess of a billion dollars) a year for individual fund managers. How do we know that “carried interest” is compensation, and not capital gain? There are several reasons:

The fund managers don’t invest their own money. They get a share of the profits in exchange for their financial expertise. If the fund loses money, the managers can walk away without any cost.[16]

A “carried interest” is much like executive stock options. When corporate executives get stock options, it gives them the right to buy their company’s stock at a fixed price. If the stock goes up in value, the executives can cash in the options and pocket the difference. If the stock declines, then the executives get nothing. But they never have a loss. When corporate executives make money from their stock options, they pay both income taxes at the regular rates and payroll taxes on their earnings.

Private equity managers (sometimes) even admit that “carried interest” is compensation. In a filing with the Securities and Exchange Commission in connection with taking its management partnership public, the Blackstone Group, a leading private equity firm, had this to say in 2007 about its activities (in order to avoid regulation under the Investment Act of 1940):

“We believe that we are engaged primarily in the business of asset management and financial advisory services and not in the business of investing, reinvesting, or trading in securities.

We also believe that the primary source of income from each of our businesses is properly characterized as income earned in exchange for the provision of services.”

The President has proposed to close the carried interest loophole, but his version of this proposal would only raise $13.8 billion over a decade, about ten billion less than the version of the proposal he offered in his first budget plan.[17] The President’s version now clarifies that only “investment partnerships,” as opposed to any other partnerships that provide services, would be affected.

[1] Citizens for Tax Justice, “The President’s Fiscal Year 2015 Budget: Business Tax Reform Provisions,” March 12, 2014. https://ctj.sfo2.digitaloceanspaces.com/pdf/obamabudgetfy2015business.pdf

[2] Chuck Marr, Jimmy Charite, and Chye-Ching Huang, “Earned Income Tax Credit Promotes Work, Encourages Children’s Success at School, Research Finds,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, revised April 9, 2013, http://www.cbpp.org/cms/index.cfm?fa=view&id=3793.

[3] Citizens for Tax Justice, “The Debate over Tax Cuts: It’s Not Just About the Rich,” July 19, 2012. http://ctj.org/ctjreports/2012/07/the_debate_over_tax_cuts_its_not_just_about_the_rich.php

[4] The Treasury notes: “As under current law, taxpayers who could be claimed as a qualifying child or a dependent would not be eligible for the EITC for childless workers. Thus, full-time students who are dependent upon their parents would not be allowed to claim the EITC for workers without qualifying children, despite meeting the new age requirements, even if their parents did not claim a dependent exemption or an EITC on their behalf.”

[5] Raj Chetty, John N. Friedman, “Soren Leth-Petersen, Torben Heien Nielsen, Tore Olsen, Active vs. Passive Decisions and Crowd-Out in Retirement Savings Accounts,” NBER Working Paper No. 18565, December 2013. http://obs.rc.fas.harvard.edu/chetty/ret_savings.html

[6] Citizens for Tax Justice, “State-by-State Figures on Obama’s Proposal to Limit Tax Expenditures,” April 29, 2013. http://ctj.org/ctjreports/2013/04/state-by-state_figures_on_obamas_proposal_to_limit_tax_expenditures.php

[7] Citizens for Tax Justice, “State-by-State Estate Tax Figures Show that President’s Plan Is Too Generous to Millionaires,” November 18, 2011. http://ctj.org/ctjreports/2011/11/state-by-state_estate_tax_figures_show_that_presidents_plan_is_too_generous_to_millionaires.php

[8] Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, “Cigarette Taxes: Issues and Options,” October 1, 2011. http://itep.org/itep_reports/2011/10/cigarette-taxes-issues-and-options.php

[9] Chuck Marr, Krista Ruffini, and Chye-Ching Huang, “Higher Tobacco Taxes Can Improve Health and Raise Revenue,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, June 19, 2013. www.cbpp.org/cms/?fa=view&id=3978

[10] Internal Revenue Service, chart titled “Tax Gap Map,” December, 2011. http://www.irs.gov/pub/newsroom/tax_gap_map_2006.pdf

[11] Citizens for Tax Justice, “The Dumbest Cut in the New Spending Deal,” January 22, 2014. http://www.ctj.org/taxjusticedigest/archive/2014/01/the_dumbest_spending_cut_in_th.php

[12] Greg Mankiw, “The Bank Tax,” January 15, 2010, Greg Mankiw’s Blog. http://gregmankiw.blogspot.com/2010/01/bank-tax.html; David Stockman, “Taxing Wall Street Down to Size,” January 19, 2010, New York Times. http://www.nytimes.com/2010/01/20/opinion/20stockman.html

[13] Citizens for Tax Justice, “How to Implement the Buffett Rule,” October 19, 2011. http://ctj.org/ctjreports/2011/10/how_to_implement_the_buffett_rule.php

[14] Citizens for Tax Justice, “Payroll Tax Loophole Used by John Edwards and Newt Gingrich Remains Unaddressed by Congress,” September 6, 2013. http://www.ctj.org/taxjusticedigest/archive/2013/09/payroll_tax_loophole_used_by_j.php

[15] Citizens for Tax Justice, Working Paper on Tax Reform Options, revised February 4, 2013. http://ctj.org/ctjreports/2013/02/working_paper_on_tax_reform_options.php

[16] Fund managers can invest their own money in the funds, but of course, tax treatment of any return on investments made with their own money would not be affected by the repeal of the carried interest loophole. (Profits from investments actually made by the managers themselves could still be taxed as capital gains).

[17] Department of the Treasury, “General Explanations of the Administration’s Fiscal Year 2013 Revenue Proposals,” February 2012, page 204. http://www.treasury.gov/resource-center/tax-policy/Documents/General-Explanations-FY2013.pdf; Department of the Treasury, “General Explanations of the Administration’s Fiscal Year 2011 Revenue Proposals,” February 2010, page 151. http://www.treasury.gov/resource-center/tax-policy/documents/general-explanations-fy2011.pdf