May 16, 2016 02:50 PM | Permalink | ![]()

Three Reasons to Reject the Dividends Paid Deduction and Corporation Integration

Since the beginning of this year, Senate Finance Chairman Orrin Hatch has been working on a proposal to “integrate” corporate and shareholder level taxes into what he calls a single level of taxation. While Sen. Hatch has yet to release a specific proposal, the Senate Finance Committee is holding a hearing on May 17 that will examine the possibility of achieving corporate integration by allowing corporations to deduct the payment of dividends to shareholders and, thus, sharply reduce their corporate income taxes.

Here are three of the biggest problems with this idea:

First, allowing dividends to be deductible at the corporate level would not lead to a single level of taxation on corporate dividend distributions. Instead, it would make most profits distributed as dividends tax-exempt at any level. Second, there is ample justification for a separate entity-level tax on corporate income. Third, at a time in which the country faces a lack of adequate revenue for public investments, corporate integration would result in a massive revenue loss from one of the country’s most progressive revenue sources.

1. Exempting corporate dividends from taxation would leave a large swath of income untaxed.

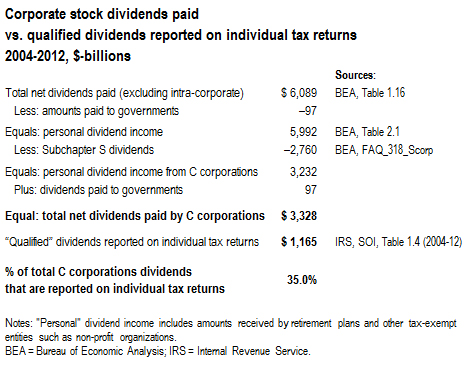

According to the most recent data from the Commerce Department’s Bureau of Economic Analysis and the Internal Revenue Service, $3.3 trillion in corporate stock dividends were paid to individuals over the nine years from 2004 through 2012 (excluding dividends from non-taxable S corporations). But less than $1.2 trillion in such dividends were reported on individual tax returns as “qualified” dividends.[1] The rest were not taxed, because they were paid to tax-exempt pension plans, other retirement plans, and other tax-exempt entities. That means that almost two-thirds of personal dividend income from corporate stock was not subject to individual income taxes.

If dividends become deductible at the corporate level, then two-thirds of dividend income would go untaxed at both the corporate and individual level. In other words, rather than eliminate supposed “double” taxation, a dividend deduction would primarily lead to zero taxation.

2. The corporate income tax is justified by the special treatment of corporations.

One of the arguments made for corporate integration is that the combination of the corporate tax and shareholder level taxes represent a form of double taxation because taxing a corporation is in effect just another tax on shareholders. While a corporation is not a person, the special privileges that corporate entities receive require that they also take responsibility as corporate citizens, which means, among other things, paying taxes.

From a legal perspective, corporations are treated as separate legal entities, which are entitled to many of the same rights as individuals. Most famously, the Supreme Court set the precedent, in Santa Clara County v. Southern Pacific Railroad, that corporations are persons for the purpose of the 14th Amendment.[2] More recently, the Supreme Court reinforced this logic in Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission, by ruling that corporations have essentially the same First Amendment rights as individuals.[3]

From an economic perspective, what distinguishes corporations that are subject to the corporate tax from those that are not is that they are given the privilege to be publicly owned, traded on a mass scale and that their owners are granted limited liability. Being granted these privileges allows them to raise large amounts of capital and play an outsized role in American economic life. In fact, corporations that are currently subject (at least in theory) to the corporate tax have 62 percent of total business receipts in the United States.[4]

Taken together, the substantial economic advantages and constitutionally granted rights given to corporations mean that they have the responsibility to support the government that grants them these very significant benefits. The public understands this principle: one recent poll found that 65 percent of Americans believe that corporations should pay more, not less, taxes.[5]

It also important to note that the existing corporate tax allows many corporations to get away with paying relatively low tax rates, with many corporations paying nothing in taxes year after year. A study by CTJ of Fortune 500 companies found that their average tax rate was just 19.4 percent or just over half the statutory corporate tax rate of 35 percent.[6]

Some advocates of corporate integration have argued that corporate integration is needed to stop the alleged erosion of the corporate tax base due to more businesses being incorporated as pass-through entities to avoid corporate taxes.[7] A better approach would be to tighten the definition of pass-through entities by lowering the number of shareholders a pass-through entity is allowed to have and by setting an income threshold over which the corporate tax will apply to pass-through entities.

3. Corporate integration is an unaffordable tax cut that would make our tax system substantially more regressive.

Despite far too many loopholes, the corporate tax is still a vital and progressive revenue source. The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) estimates that the federal government will collect $357 billion in corporate tax revenues in 2017 and about $4 trillion over the next decade.[8] Corporate taxes have fallen from more than a third of total federal taxes in earlier decades to just a tenth in recent years.[9] Considering our government’s need for more tax revenue to reduce the deficit and fund essential programs, corporations should be paying more, not less, in taxes.[10]

In addition to providing significant revenues, the corporate tax increases the fairness of our tax system, because it is one of the most progressive forms of taxation. Virtually all analysts conclude that most, if not all, of the corporate tax is ultimately borne by shareholders.[11] As a result, about half of the corporate tax is paid by the wealthiest 1 percent of taxpayers, and nearly three-quarters is paid by the top 5 percent.[12]

Enacting a corporate dividends deduction could mean the loss of roughly $150 billion in corporate tax revenue each year. Even if some of that cost is offset by taxing personal dividends at regular tax rates rather than at the preferential capital gains tax rates, the fact most dividends are not taxed at the personal level would still leave a very large cost. Every dollar lost in corporate revenue is likely to be made up for either through the loss of revenue for important public investments or through higher taxes on low- and middle income families. Low- and middle-income families are already struggling due to growing income inequality and government austerity. Substantially cutting one of the most progressive sources of revenue would make our tax system less fair.

[1] IRS Statistics of Income for qualified dividends reported on individual tax returns. Bureau of Economic Analysis, FAQ_318_Scorp for total corporate dividends paid (excluding Sub S dividends).

[2] John Witt, “What Is The Basis For Corporate Personhood?” October 24, 2011. http://www.npr.org/2011/10/24/141663195/what-is-the-basis-for-corporate-personhood

[3] Lyle Denniston, “Analysis: The personhood of corporations,” January 21st, 2010. http://www.scotusblog.com/2010/01/analysis-the-personhood-of-corporations

[4] IRS, “SOI Tax Stats – Integrated Business Data: Table 1: Selected financial data on businesses,” April 15, 2015. https://www.irs.gov/uac/SOI-Tax-Stats-Integrated-Business-Data

[5] Americans for Tax Fairness, “Polling on Tax Fairness Issues,” March 19, 2015. http://www.americansfortaxfairness.org/files/3.19.15-ATF-Polling-Questions-on-Tax-Fairness-Issues-Final.pdf

[6] Citizens for Tax Justice, “Sorry State of Corporate Taxes,” February 4, 2015. http://www.ctj.org/corporatetaxdodgers/

[7] Tax Foundation, “Eliminating Double Taxation through Corporate Integration.” February 13, 2015. http://taxfoundation.org/article/eliminating-double-taxation-through-corporate-integration

[8] Congressional Budget Office, “Updated Budget Projections: Fiscal Years 2016 to 2026,” March 4, 2016. https://www.cbo.gov/publication/51384

[9] Office of Management and Budget: “Table 2.2—Percentage Composition of Receipts by Source: 1934–2018”, http://www.whitehouse.gov/omb/budget/Historicals

[10] Citizens for Tax Justice, “U.S. Corporations Should Pay More, Not Less, in Taxes,” November 7, 2012. https://ctj.sfo2.digitaloceanspaces.com/pdf/corporatetaxfactsheet.pdf

[11] Congressional Budget Office, “Working Paper 2010-03: Corporate Tax Incidence: Review of General Equilibrium Estimates and Analysis.” May 20, 2010, http://www.cbo.gov/publication/21486

[12] Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy Tax Model, April 2013