April 10, 2012 11:52 AM | Permalink | ![]()

Congress should approve Senator Sheldon Whitehouse’s proposal to implement the “Buffett Rule” to raise badly needed revenue and make our tax system fairer, but should also recognize that this must be followed by far more substantial reforms. In particular, Congress can’t stop at limiting breaks for millionaire investors but should completely repeal the personal income tax preference for investment income, as President Ronald Reagan did in 1986.[1]

A previous CTJ report concluded that Senator Whitehouse’s bill would raise $171 billion from 2013 through 2022.[2] The non-partisan Joint Committee on Taxation (JCT) has estimated that it would raise much less revenue, probably because JCT overestimates behavioral responses to changes in tax rates on investment income.[3] But even if Senator Whitehouse’s bill would raise $171 billion over a decade, that’s only a fraction of the $533 billion that CTJ estimates could be raised by completely ending the tax preference for investment income.

Why We Need the Buffett Rule

The “Buffett Rule” is the principle, proposed by President Barack Obama, that the tax system should be reformed to reduce or eliminate situations in which millionaires pay lower effective tax rates than many middle-income people.

An earlier report from Citizens for Tax Justice explains how multi-millionaires like Warren Buffett who live on investment income can pay a lower effective tax rate than working class people.[4] As the report explains, there are two reasons for this. First, the personal income tax has lower rates for two key types of investment income, long-term capital gains and stock dividends. Second, investment income is exempt from payroll taxes (which will change to a small degree when the health care reform law takes effect).[5]

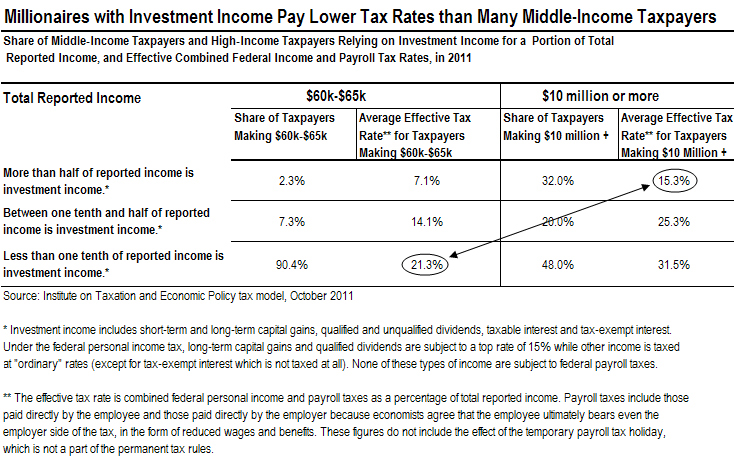

The report compares two groups of taxpayers, those with income in the $60,000 to $65,000 range (around what Buffett’s secretary is said to make), and those with income exceeding $10 million.

For the first group, about 90 percent have very little investment income (less than a tenth of their income is from investments) and consequently have an average effective tax rate of 21.3 percent. For the second group (those with incomes exceeding $10 million), about a third get a majority of their income from investments and consequently have an average effective tax rate of 15.3 percent. This is the fairness problem that the “Buffett Rule” would address.

The Best Way to Implement the Buffett Rule: End the Tax Preference for Investment Income

The most straightforward way to implement the Buffett Rule would be to eliminate the personal income tax preferences for investment income. This would mean, first, allowing the parts of the Bush tax cuts that expanded those preferences to expire. Second, Congress would repeal the remaining preference for capital gains income, which would raise $533 billion over a decade.

The most straightforward way to implement the Buffett Rule would be to eliminate the personal income tax preferences for investment income. This would mean, first, allowing the parts of the Bush tax cuts that expanded those preferences to expire. Second, Congress would repeal the remaining preference for capital gains income, which would raise $533 billion over a decade.

When President George W. Bush took office, the top tax rate on long-term capital gains was 20 percent, and the tax changes he signed into law in 2003 reduced that top rate to 15 percent. The same law also applied the lower capital gains rates to stock dividends, which previously were taxed as ordinary income. If the Bush tax cuts, which were extended through 2012, are allowed to expire, then capital gains will again be taxed at a top income tax rate of 20 percent (meaning there will still be a tax preference for capital gains) and stock dividends will once again be taxed like any other type of income.

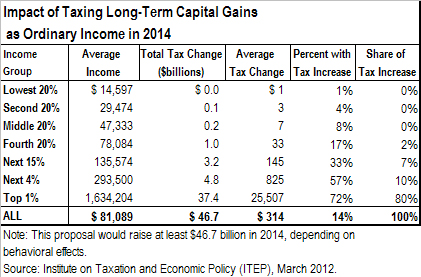

The Bush tax cuts for capital gains and dividends should be allowed to expire at the end of this year. In addition, Congress should repeal the capital gains break that will still exist (the special rates not exceeding 20 percent). Under this proposal, capital gains would simply be taxed at ordinary income tax rates. This would raise at least $533 billion over a decade. [6] The table above shows that 80 percent of the tax increase resulting from eliminating the capital gains preference would be paid by the richest one percent of taxpayers in 2014.

Senator Sheldon Whitehouse’s Buffett Rule Bill

Senator Sheldon Whitehouse of Rhode Island has introduced a bill that would take a more roundabout approach to implementing the Buffett Rule by imposing a minimum tax equal to 30 percent of income on millionaires. This would raise much less revenue than simply ending the break for capital gains, for several reasons.

Senator Sheldon Whitehouse of Rhode Island has introduced a bill that would take a more roundabout approach to implementing the Buffett Rule by imposing a minimum tax equal to 30 percent of income on millionaires. This would raise much less revenue than simply ending the break for capital gains, for several reasons.

First, taxing capital gains as ordinary income would subject capital gains to a top rate of 39.6 percent in years after 2012, while Senator Whitehouse’s minimum tax would have a top rate of just 30 percent. Second, the minimum tax for capital gains income would effectively be even less than 30 percent because it would take into account the 3.8 percent Medicare tax on investment income that was enacted as part of health care reform. Third, while most capital gains income goes to the richest one percent of taxpayers, there is a great deal of capital gains that goes to taxpayers who are among the richest five percent or even one percent but who are not millionaires and therefore not subject to the Whitehouse proposal.

Other reasons for the lower revenue impact of the Whitehouse proposal (compared to repealing the preference for capital gains) have to do with how it is designed. For example, Senator Whitehouse’s minimum tax would be phased in for people with incomes between $1 million and $2 million. Otherwise, a person with adjusted gross income of $999,999 who has effective tax rate of 15 percent could make $2 more and see his effective tax rate shoot up to 30 percent. Tax rules are generally designed to avoid this kind of unreasonable result.

The legislation also accommodates those millionaires who give to charity by applying the minimum tax of 30 percent to adjusted gross income less charitable deductions.

These provisions would not be necessary if Congress took the more straightforward approach of simply ending the tax preferences for investment income, which would simply require that all income be taxed at the same rates.

Photo of Warren Buffett and Sheldon Whitehouse via The White House and Transportation for America Creative Commons Attribution License 2.0

[1] The Tax Reform Act of 1986, signed into law by President Ronald Reagan, ended the tax preference for capital gains and resulted in a personal income tax that imposed the same rates on all types of income.

[2] Citizens for Tax Justice, “Policy Options to Raise Revenue,” March 8, 2012. https://ctj.sfo2.digitaloceanspaces.com/pdf/revenueraisers2012.pdf

[3] The Joint Committee on Taxation (JCT) estimated that Senator Whitehouse’s bill would raise $47 billion over a decade. James O’Toole, “Buffett Rule would Raise Less than $5 Billion in Taxes a Year,” March 20, 2012. http://money.cnn.com/2012/03/20/news/economy/buffett-rule-analysis/index.htm CTJ’s report, “Policy Options to Raise Revenue,” includes an appendix that describes the literature concluding that JCT overestimates behavioral responses to taxes on capital gains.

[4] Citizens for Tax Justice, “How to Implement the Buffett Rule,” October 19, 2011. https://ctj.sfo2.digitaloceanspaces.com/pdf/buffettruleremedies.pdf; Citizens for Tax Justice, “The Need for the ‘Buffett Rule’: How Millionaire Investors Pay a Lower Rate for Middle-Class Workers,” September 27, 2011. https://ctj.sfo2.digitaloceanspaces.com/pdf/buffettrulereport.pdf

[5] The health care reform law effectively expanded the Medicare tax to include a top rate of 3.8 percent and to apply to investment income for taxpayers with adjusted gross income in excess of $250,000 for married couples and $200,000 for single taxpayers.

[6] Figures used here incorporate the assumptions of the Congressional Budget Office that capital gains income will decline in 2013, presumably in response to the end of the Bush tax cuts, and then quickly recover in years after that.