May 27, 2014 08:17 AM | Permalink | ![]()

A few days after Americans filed their tax returns last month, the Internal Revenue Service released data on the offshore subsidiaries of U.S. corporations. The data demonstrate, in an indirect way, that these companies are not playing by the same rules as the rest of us.

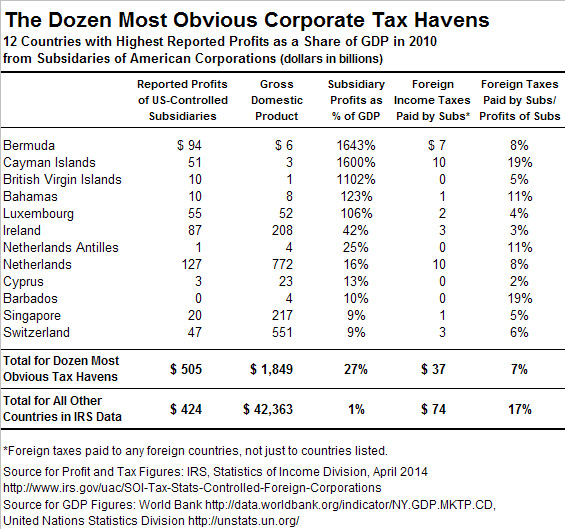

The figures show how much profit American corporations tell the IRS that their subsidiaries have earned in each foreign country. Amazingly, American corporations reported to the IRS that the profits their subsidiaries earned in 2010 in Bermuda, the Cayman Islands, the British Virgin Islands, the Bahamas and Luxembourg were greater than the entire gross domestic product (GDP) of those nations in that year.

It is obviously impossible for American corporations to actually earn profits in a given country that exceed that country’s total output of goods and services. Clearly, American corporations are using various tax gimmicks to shift profits actually earned in the U.S. and other countries where they actually do business into their subsidiaries in these tiny countries. This is not surprising, given that these countries impose little or no tax on corporate profits.

Besides the five countries just mentioned, the data also indicate that other countries also serve as tax havens for American multinational corporations. For example, American corporations report to the IRS that the profits their subsidiaries earned in Switzerland were equal to 9 percent of Switzerland’s GDP. This is a much higher share of GDP than the profits reported in more significant European countries: about half a percent of GDP in Germany and France, and 3 percent in the United Kingdom. This suggests that American corporations are exaggerating how much of their profits are earned in Switzerland, which is not surprising given that some corporations are able to obtain very low tax rates in that country.

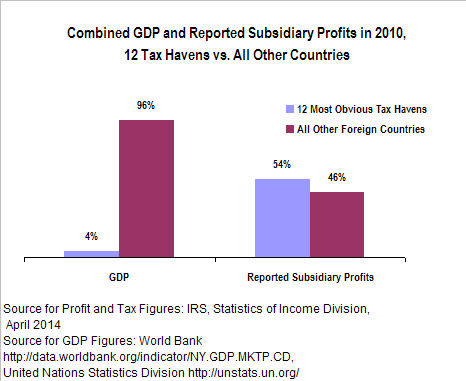

The dozen countries with the highest reported American offshore corporate profits as a percentage of their GDP in 2010 had only four percent of the total GDP for all the foreign countries included in the IRS figures. But American corporations report to the IRS that 54 percent of their offshore subsidiary profits were earned in these tax-haven countries. This is obviously impossible. The only plausible conclusion is that American corporations are engaging in various accounting gimmicks to make large amounts of their profits appear, for tax purposes, to be earned in these dozen tax-haven countries.

These 12 countries have either zero tax rates or provide loopholes that allow corporate profits to go largely untaxed in many circumstances. The two columns on the right side of the table on page one show the amount of corporate income taxes paid on the subsidiary profits to the country where they were supposedly earned or any other foreign country. This is shown first as a dollar figure and then as a percentage of the profits supposedly earned in that country.

There are apparently foreign income taxes paid on some profits even in countries known to have a zero corporate tax rate like Bermuda or the Cayman Islands. This may often occur because the profits are shifted from a subsidiary in another foreign country that imposes some tax on profits when they are shifted to a tax haven country. Overall, however, these subsidiary corporations are able to avoid paying almost any taxes. The effective rate of foreign taxes paid on subsidiary profits in the dozen countries was only 7 percent.[1]

The U.S. allows its corporations to defer paying U.S. corporate income taxes on profits of their offshore subsidiaries until those profits are officially “repatriated” (officially brought to the U.S.). This creates an incentive for American corporations to engage in accounting gimmicks to make their U.S. profits appear to be earned in countries where they will not be taxed. These data demonstrate that this is happening on a large scale. In fact, American corporations reported that more than half a trillion dollars of their profits were earned, for tax purposes, in the 12 tax haven countries shown in the table.

Amazingly, some lawmakers are calling for even greater tax breaks for the offshore profits of American corporations. Some proposals would largely exempt previously accumulated offshore profits from U.S. taxes on an (allegedly) one-time basis (often called a “repatriation holiday”). Others would provide a permanent exemption (often called a “territorial tax system”). Perhaps these lawmakers do not realize that over half of the profits that American corporations claim their subsidiaries earn offshore — over half of the profits that could benefit from such new tax breaks — are reported by the companies to have been earned in 12 obvious tax havens.

Corporate profits that are genuinely earned through real business activities abroad are typically subject to taxes in the countries where they are earned, and if they are repatriated, the U.S. tax that is due is reduced by whatever amount of tax was paid to foreign governments. For this reason, the only offshore profits that are potentially subject to nearly the full 35 percent U.S. tax rate upon repatriation are those artificially shifted to tax havens. Companies engaging in these tax-avoidance games would therefore be the main beneficiaries of a repatriation holiday or territorial system.

Congress could end this corporate tax avoidance in a straightforward way by ending the rule allowing American corporations to defer paying U.S. taxes on their offshore subsidiary profits. They would still be allowed to reduce their U.S. income tax bill by whatever amount of tax was paid to foreign governments, in order to avoid double-taxation. But there would no longer be any reason to artificially shift profits into tax havens because all profits of American corporations, whether earned in the U.S. or in any other country, would be taxed at least at the U.S. corporate tax rate in the year they are earned.

[1] The Tax Foundation recently issued a report stating that the “effective tax rate on foreign income was 27.2 percent in 2010, prior to paying additional taxes to the United States,” but that report only examines those offshore subsidiary profits actually repatriated to the U.S. Of course, the offshore profits most likely to be repatriated are those that were taxed at relatively high rates by foreign countries, because these profits generate the largest foreign tax credits that reduce the U.S. tax that would be due upon repatriation. For the same reason, tax haven profits, which generate little or no foreign tax credits, are not as likely to be repatriated. In other words, the Tax Foundation report simply excludes tax haven profits from its analysis of foreign taxes paid on subsidiary profits. See Kyle Pomerleau, “How Much Do U.S. Multinational Corporations Pay in Foreign Income Taxes?,” Tax Foundation, May 19, 2014.